The Power Of ‘I Don’t Know’ In The Learning Process

by Terry Heick

At TeachThought, nothing interests us more than students—as human beings. What they know, might know, should know, and do with what they know.

A driving strategy that serves students–whether pursuing self-knowledge or academic content–is questioning. Questioning is useful as an assessment strategy, catalyst for inquiry, or “getting unstuck” tool. It can drive entire unit of instruction as an essential question. In other words, questions transcend content, floating somewhere between the students and their context.

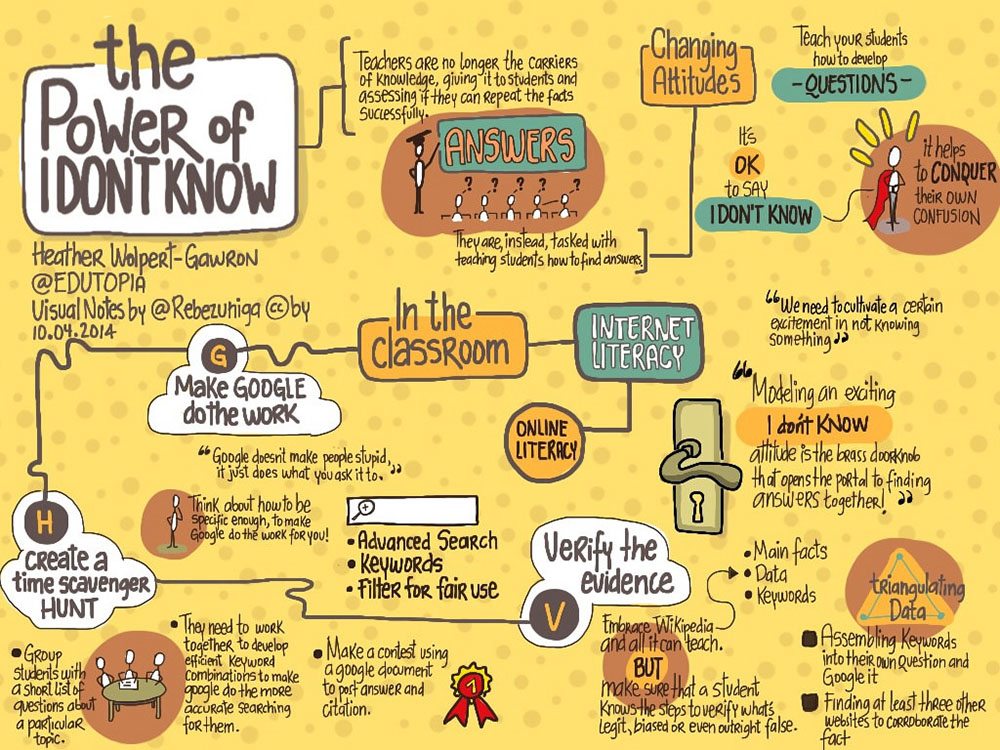

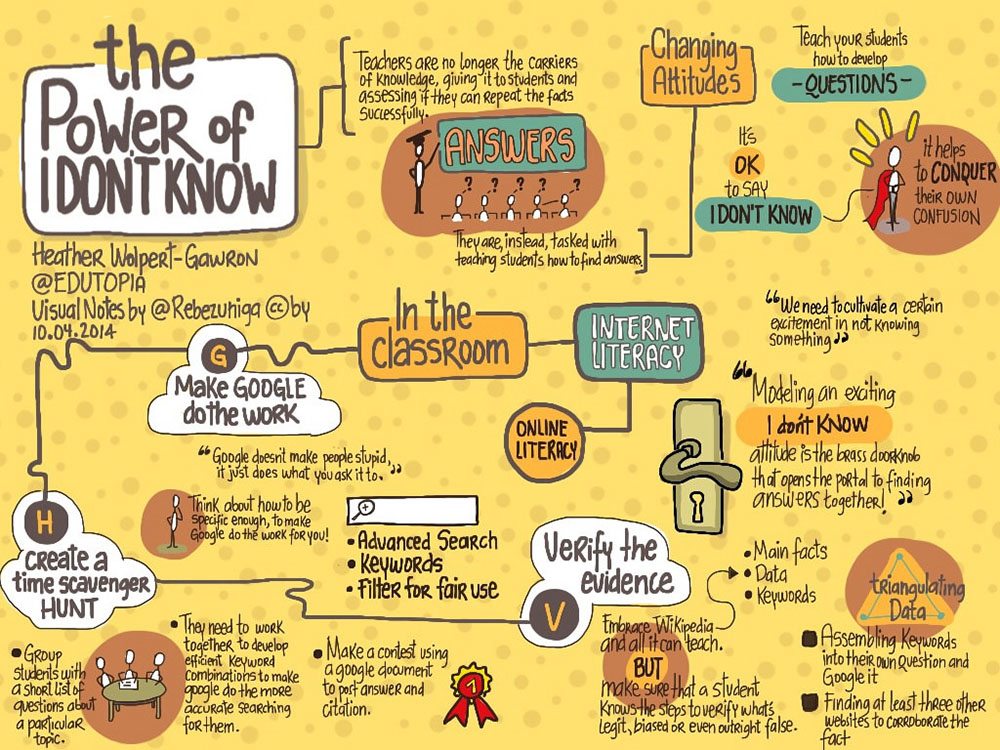

Questions are more important than the answers they seem designed to elicit. The answer is residual–requires the student to package their content to please the question-maker, which moves the center of gravity from the student’s belly to the educator’s marking pen. In that light, I was interested when I found the visual above.

It’s okay to say “I don’t know.” Teach your students how to develop questions (because) it helps conquer their own confusion.

Rebeca Zuniga was inspired to create the above visual by the wonderful Heather Wolpert-Gawron (from the equally wonderful edutopia, and also her own site, tweenteacher). The whole graphic is wonderful, but it’s that I don’t know that really resonated with me. Traditionally, this phrase is seen as a hole rather than a hill. I don’t know means I’m missing information that I’m supposed to have.

See Also Sentence Stems To Replace ‘I Don’t Know’ or ‘I Can’t’

The implication of a question is that the student should have (some kind of answer). See that–what’s happening there? The teacher’s whispering, “I know the answer. You should, too. Answer my question and you’ll have the answer.” And? Whoopty do.

The value (of an answer) was granted by the teacher. It’s teacher-currency. There is value in answers as knowledge, but there is lasting power in inquiry because it’s a student-centered and self-sustaining process. In part, this is because returns the center of gravity back to the student, where it belongs. It short-circuits that dog-and-pony show of classroom teaching and makes it something shaped like the student’s mind.

I don’t know, then, isn’t just a starting point for finding an answer, or a ready-made template for some academic essential question. Rather, it returns the learning to the student and restores the scale of understanding to a universe of knowledge.

Teacher: What form of government is most likely to encourage innovation?

Student: A democracy?

Teacher: Why?

Student: Because there is a lot of innovation in the United States, and we’re a democracy?

Teacher: Is that innovation occurring because of or in lieu of that form of government?

Student: Because of.

Teacher: Why do you think that?

Student: I don’t know.

Here, there’s a shift. It’s no longer a cat-and-mouse game. Now there’s emotion involved. The gravity is with the student. The burden is in her lap, but since there is no clear path forward, the scale of things–the context–moves from beyond an interaction between a teacher and student to everything else but the interaction between the teacher and the student. The answer isn’t here. It’s out there. Out there is where I need to be.

The learning has left the classroom; now it can grow.

The Power Of I Don’t Know; image attribution flickr user Rebecca Zuniga