Merging Metacognition & Citizenship

by Terrell Heick

Ed note: This post parallels our self-directed learning model.

Why should someone learn?

While Paulo Freire, John Dewey, and others have provided compelling arguments for what might be the goal of education, learning, and education are not one and the same. One simple overarching goal of learning, as opposed to education might be for each learner to understand ‘how to work well in one’s place.’

Learning—here defined as the overall effect of incrementally acquiring, synthesizing, and applying information—changes beliefs. Awareness leads to thoughts, thoughts lead to emotions, and emotions lead to behavior. Learning, therefore, results in both personal and social change through self-knowledge and healthy interdependence. In fact, this may be the truest–and wordiest–definition of modern learning possible: intimate, self-directed learning experiences that serve authentic physical and digital communities, ultimately leading to personal and social change.

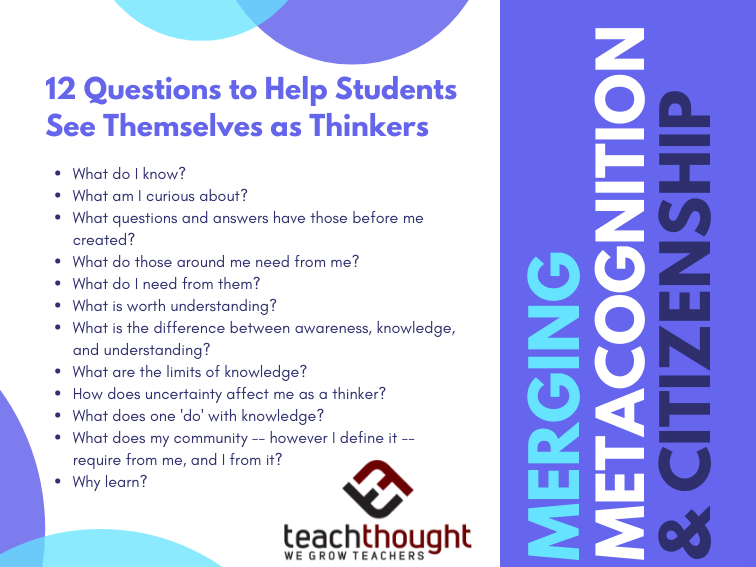

12 Questions To Help Students See Themselves As Thinkers

Self-knowledge is formed through a range of meta-cognition and basic epistemology.

1. What do I know?

2. What am I curious about?

3. What questions and answers have those before me created?

4. What do those around me need from me?

5. What do I need from them?

6. What is worth understanding?

7. What is the difference between awareness, knowledge, and understanding?

8. What are the limits of knowledge?

9. How does uncertainty affect me as a thinker?

10. What does one ‘do’ with knowledge?

11. What does my community–however I define it–require from me, and I from it?

12. Why learn?

Globalization & Citizenship

Authentic self-knowledge and accountable local placement promote healthy communities that can solve problems and celebrate knowledge on a scale that resonates globally. But what does this mean to the learner—the individual that should be the focus of any learning process, platform, or initiative?

See also This Math Problem Has Gone Viral Because PEMDAS Confuses People

How should the role of the teacher change in light of modern access to information in much of the world? (And how is information different than knowledge?)

How can education possibly maintain the pace of change in technology? What are the consequences if it doesn’t?

Since globalization is, first and foremost, a matter of local citizenship, a question must be considered: where does citizenship begin?

Essayist and social critic Wendell Berry, for years, has addressed large questions regarding the intersection of the individual, society, business, and technology. Berry cautions that a “refined, discriminating knowledge of localities by the local people is indispensable if we want the most sensitive application of intelligence to local problems if we want the best work to be done.”

One interpretation of this idea references the notion of scale; in fact, most challenges of application (in this case, learning) can be reduced to challenges in scale. An implication then would be for one to design a ‘scaleable’ curriculum by, among other things, beginning and ending with the local ‘self.’

In lieu of outward content knowledge, perhaps the goal of all learning should be self-knowledge–themes of identity and purpose, then connectivism and interdependence–ultimately leading to self-directed thinkers who care for their connections with others and the consequences of their ‘cognitive behavior.’

This ‘self-caretaking’ radically differs from externally-directed, measured, and motivated performance in tone and purpose. But this redirect of the purpose of learning isn’t just about motivation or a classroom striving to be ‘learner-centered’–it’s about re-centering the entire learning process.

Alone this is a minor shift, but on a macro level, this kind of thinking might lead to innovative, ‘different’ thinking by a new kind of learner who just has to solve a problem, correct a conflict, or create art.

Masterpieces are rarely created under compulsion.