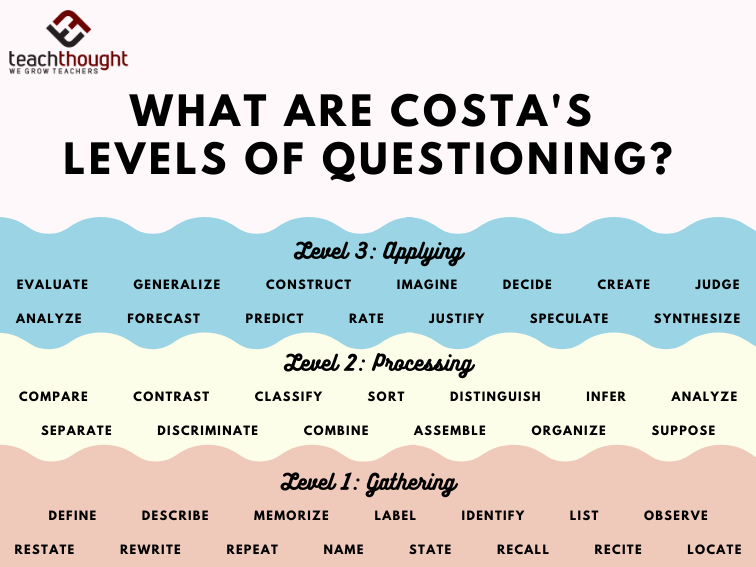

Costa’s Levels of Questioning

Costa’s Levels of Questioning — designed by educational researcher Art Costa — feature three tiers of questioning designed to promote higher-level thinking and inquiry.

Similar to Bloom’s Taxonomy framework, Costa’s lower level prompts students to use more basic faculties; as students move up in levels, the questions prompt them to use more complex thinking skills. Through decades of research on human resilience, Dr. Costa also identified the 16 Habits of Mind, a set of behaviors that support students in navigating the challenges that often occur in school and life, in general. Several of Dr. Costa’s 16 habits — thinking interdependently, innovating, gathering data, and applying past knowledge to new situations — both require and reinforce higher levels of questioning.

There is a substantive amount of research that supports Dr. Costa’s schema. Newmann (1993) found that higher-order thinking compels students to “manipulate information and ideas in ways that transform their meaning,” and “expects students to solve problems and develop meaning for themselves,” which aligns with a constructivist view of education.

Costa’s Levels of Questioning are typically illustrated using the metaphor of a house with three floors:

Level 1: Gathering

Level 1 questions focus on the retrieval and identification of explicitly stated information within a text. These questions assess a reader’s ability to locate specific details, facts, or statements that are directly presented in the source material.

Responses to Level 1 questions are characteristically literal in nature—the required information can be directly extracted from the text without requiring interpretation or inference. This level emphasizes surface-level comprehension and the fundamental skill of accessing information as it is explicitly presented.

We’ve previously written about Bloom’s Taxonomy power verbs, and Costa’s levels have their own set of power verbs, as well. Here are a few that you might find at the start of Level 1 questions:

- Define

- Describe

- Memorize

- Label

- Identify

- List

- Observe

- Restate

- Rewrite

- Repeat

- Name

- State

- Recall

- Recite

- Locate

- Select

- Match

- Show

Level 1 questions by content area might look like these examples:

- Science: Label the parts of an animal cell.

- Math: Recite the formula for finding the volume of a cylinder.

- Social Studies: Match the name of the monarch to their respective country.

- English Language Arts: Locate the place in the plot where the climax occurs.

You can see how most of these Level 1 power verbs require students to recall information, which is an important skill in its own right. Nonetheless, teachers should strive for the majority of their questions to fall in Level 2 or 3, which challenge students to use higher-order thinking skills.

Level 2: Processing

Level 2 questions go a step further than Level 1, prompting students to process information by ‘reading between the lines.’ While students may need to use literal information to formulate their responses, Level 2 requires them to process that information with what they already know in order to make new connections.

Here are some examples of Level 2 power verbs:

- Compare

- Contrast

- Classify

- Sort

- Distinguish

- Infer

- Analyze

- Separate

- Discriminate

- Combine

- Assemble

- Organize

- Suppose

Level 2 questions by content area might show up in the following ways:

- Science: Compare the processes of mitosis and meiosis.

- Math: Classify the geometric shapes according to their number of sides and angles.

- Social Studies: Assemble the following historical events in the order of significance, from most to least.

- English Language Arts: Analyze the impact that the author’s tone has on the overall meaning of the text.

Can you see how Level 2 questions go a step further than Level 1? More than simply regurgitating information, learners take it and ‘do something’ with it. They categorize, make distinctions, and compare/contrast it against another part to see how it affects the whole. These kinds of skills can stimulate curiosity and build a bridge to the questions that really generate creativity and higher-level thinking.

Level 3: Applying

While Level 1 questions prompt students to work with input, and Level 2 questions challenge them to process that input in order to make new connections, in Level 3 (Application) questions, students engage in the highest-level thinking skills to create an output. This could result from making evaluations and analyses, testing solutions to various problems, or making predictions.

We’ve included some examples of Level 3 power verbs below:

- Evaluate

- Generalize

- Construct

- Imagine

- Decide

- Create

- Judge

- Analyze

- Forecast

- If/then

- Predict

- Rate

- Justify

- Speculate

- Synthesize

- Build

- Hypothesize

Level 3 questions by content area might look like the following:

- Science: Based on data from the last decade of hurricane activity in the southeast U.S., predict how the frequency of hurricane activity will change in the next ten years.

- Math: Rate the probability of a presidential candidate winning the election based on securing the electoral votes from the following U.S. states: Florida, California, Virginia, New York, Illinois.

- Social Studies: Create a social compact that considers the effects of globalization and technological advancement in the 21st century.

- English Language Arts: Build an argument that defends or refutes mandatory employee vaccination policies in the United States.

Instructional Application

Effective question design should emphasize processing and transfer (Levels 2 and 3) rather than recall (Level 1). Research on cognitive complexity indicates that questions requiring only factual retrieval, such as identifying dates, names, or formulas, provide limited evidence of student understanding or ability to apply knowledge in novel contexts (Brookhart, 2022; McTighe & Silver, 2020).

Level 2 and 3 questions require students to manipulate, analyze, or extend information rather than simply locate it. Consider the difference between these approaches:

- Level 1: When did the Civil Rights Act pass?

- Level 2: How did the timing of the Civil Rights Act relate to concurrent social movements?

- Level 3: Given current sociopolitical conditions, what structural barriers would similar legislation face today?

Similarly, asking students to identify an author’s name differs substantially from asking them to apply that author’s rhetorical approach to contemporary issues, the latter requiring synthesis, transfer, and evaluative judgment.

Higher-order questions create cognitive disruption. Baldwin (1963) described the inherent tension in education: “The paradox of education is precisely this, that as one begins to become conscious one begins to examine the society in which he is being educated” (pp. 42-44). Questions at Levels 2 and 3 operationalize this principle by requiring students to interrogate assumptions, identify contradictions within systems, and generate solutions to authentic problems.

Such questions distinguish between knowledge demonstration and knowledge application, essential for assessing deeper learning, defined as “the process through which an individual becomes capable of taking what was learned in one situation and applying it to new situations” (National Research Council, 2012, p. 5).