What Does Jeremy Lin’s Success Mean For Education?

The Backstory Part

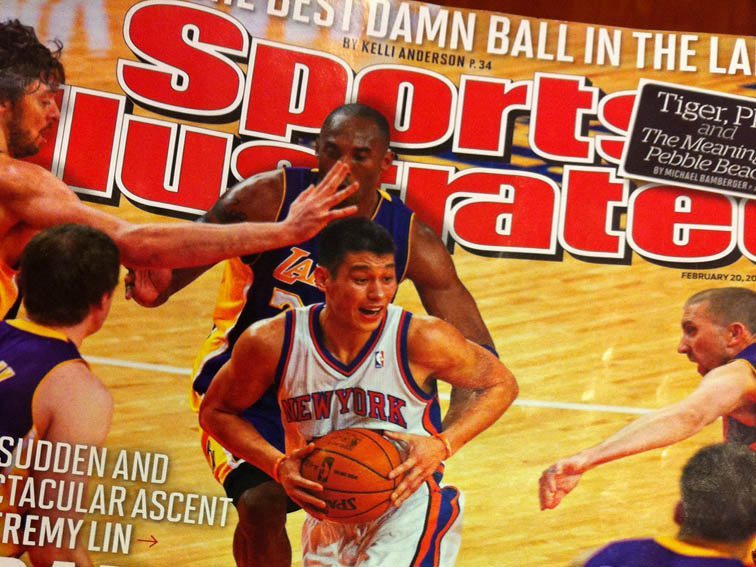

By now, even if you’re not a sports fan you’ve probably heard of Jeremy Lin. This time last year the California-born point guard was running the New York Knicks, and in doing so became an overnight sensation in the NBA, taking a struggling Knicks franchise and single-handedly rejuvenating it in the process. He has since been traded to the Houston Rockets after failing to mesh with the mercurial Carmelo Anthony, but there’s something to be learned here.

On February 4, 2012, with injuries and mediocre performance plaguing the team, Knicks head coach Mike D’Antoni—his job likely on the line—inserted the seldom-used Lin into the starting lineup. The result? The Knicks reeled off 8 wins in 9 games. According to the Elias Sports Bureau, only four players since the 1977-1978 ABA-NBA merger have scored more points in their first 8 starts than Lin.

This is and of itself wouldn’t generate such attention. But add in themes of diversity and underdogs—two stalwarts of American spectacle—all in the city of New York, and there is something to see. Lin’s family is from Taiwan, and Lin himself is only 6’3”, relatively short by NBA standards. And his college background? Not the University of Kentucky, North Carolina, or other “high major” basketball programs. Lin went to Harvard–and not because Harvard was his first choice, but because there was little to no interest from other universities.

While Harvard is legendary for their academic rigor, if you want to play basketball at the highest level, it’s not your first choice. Lin eventually performed well at Harvard, and bounced around a few teams in the NBA before finding real opportunity with the Knicks.

So what do you get when you take the first Harvard-educated NBA player in half a century, and add the additional wrinkle that he’s also the first American-born Asian to achieve such public NBA success?

In New York City of all places?

You get sensationalism of course, and crossover stories like these. But maybe there’s something worth considering for the TeachThought audience.

What This Has To Do With Education

Current education systems are predicated on data-based revision of existing processes. While charter schools get headlines for tinkering with education rules and forms, true innovation has been scarce, happening on very small scales, or in difficult-to-duplicate ways.

With so much of “performance” now highly visible, and so little substantive two-way communication between communities and schools on initiatives moving forward, the challenge isn’t generating new ideas, but perhaps rather trusting change. It would’ve been difficult to predict Lin’s formula for success ahead of time. Let’s consider Lin’s situation a kind of analogue for education.

Why Lin’s Plight Works As An Analogue

1. He was of average height and average athleticism. On paper, there was nothing to be excited about regarding Lin. (Insert lukewarm reception of specific innovative education idea here.)

2. Early results were not promising, with Lin failing to even score in double figure in his first 22 games with the Knicks. (Consider “the implementation dip,” where newfound initiatives take time to show results.)

3. Beyond games, Lin had countless opportunities in practice to catch the eyes of coaches, but never did so with enough fervor to warrant extended playing time. (Imagine a learning strategy or assessment form that is barely passable under certain conditions–socioeconomic conditions, for example–but in others, soars.)

4. But Knicks coach D’Antoni saw something. He stuck with Lin—and not without supporting tweaks. He altered the Knicks attack, gave Lin more room to be creative with the ball, and simplified certain offensive sets to take advantage of Lin’s unique gifts. (Imagine implementing a new iPad program in your school, the curriculum around it would have to be not only modified, but flexible enough itself to be modified, as would parent understanding of the learning process, district “non-negotiables”, and so on.)

Players around Lin also had to adjust to Lin’s unique talents. He was different than other guards they’d played with in the past—able to beat other players off the dribble not so much with quickness or athleticism as determinism and timing. But unlike other “crafty” NBA players such as Steve Nash, Lin could finish well at the rim. Defying racial stereotypes, Lin could not only score with “swagger,” but he could do so with authority, spinning, crossing over, and dunking like seasoned stars.

He was, in short, an enigma.

Conclusion

Part of the challenge with innovating in education lies in its inherent inertia. So much is interdependent that if you change one thing (e.g., standards), other components need to be changed as well (e.g., assessment)—and all the bureaucracy that comes along for the ride. This isn’t as simple as inserting a new person to play the same position with the same responsibilities on the same team. But what if change in education was possible—through technology, through social media forms, through intense community/school collaboration—without (literal) acts of Congress?

While there are undoubtedly lessons in Lin’s story about the value of diversity, open-mindedness, and persistence, perhaps the greatest lesson to take away from Jeremy Lin’s meteoric NBA success is to realize that it hasn’t been meteoric at all. It has been long-in-development, and the result of flexibility and timing on the part of stakeholders.

The application for teachers? Honoring the unpredictable but numerous possibilities for innovating and improving education—first on small, manageable scales (communities, programs, and schools), and then collaboratively, through technology, in larger venues (districts, states, and national organizations).

One can read Lin’s situation and spin it in a dozen ways, from the value of patience, to the reality of the still-very-much-alive American dream. Personally I tend towards chaos. In the end, it’s impossible to script success no matter the rhetoric that promises otherwise. So why not back away from institutionally-centered education reform–programs, policies, and one-size-fits-all curriculum–and “open source” the learning process entirely.

Setup the fundamental pieces of a model, and then back away.

Completely away.

Let evolution and local innovation take hold and resist the urge to muck it up with policy, pressure, and spectacle.

Somewhere in education, there is a Jeremy Lin with an idea that could revolutionize learning–an app, a learning model, a concept for a school, a new curriculum framework. None of this will matter if he never gets a chance, but chances on the big stage of public education don’t come along very often.

This, then, is fundamentally an argument in favor not just of opportunity, but diversity. More learning forms, more visions, more models, more thinking not just socialized but put into action no matter how funny it might look on the surface. If it’s sufficiently radical, it will likely appear disarmingly different. Could even be scary. What on earth do we have to be scared of?

At one point Jeremy Lin sat on the Knick’s bench quietly and look like 6 feet and three inches of mediocre point guard. Not much spectacle, and certainly nothing that shook the NBA paradigm. A year later, he is averaging 12 points and 6 assists a game battling a point-guard heavy league each night, and more than holding his own.

For most mass media, he is a cultural story. For education, he is an argument for diversification.

This piece was originally written by Terry Heick for Edudemic Magazine