6 Reasons Standardized Testing Is, At Best, Problematic

contributed by Sara Briggs

1. Misused And Punitive Data

“Before Jesus Christ was born, human beings were taking tests,” writes Amanda Ripley for Education Nation. “Civil service exams date back to China’s Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD.) Hiring test-prep tutors—and cheating— go back about as far, by the way.”

And when she says “cheating,” Ripley is hardly referring to the students themselves. She’s referring to school systems, policymakers, and anyone else who cheats students out of opportunities for success by maintaining the status quo.

Schools and districts across the United States have been caught cheating— changing test answers or giving their students test problems ahead of time— including Atlanta, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and Texas. A March, 2011 USA Today investigation showed that the dramatic rise in D.C. test scores was due to cheating, not to effective administration. There have also been instances in which tests were scored incorrectly, failing and sending students who had actually passed the tests to summer school.

In October 2010, the Chicago Tribune reported that when Illinois adjusted the ISAT scoring system in 2006, it “lowered the number of points required to pass,” resulting in more students appearing proficient than was actually the case. A recent study by the Chicago Consortium on School Research found that, after controlling for differences in assessments and changing demographics, there was essentially no increase in scores of elementary students over two decades of test-driven reform.

If the tests we use to measure student learning are themselves invalid, then the inferences we draw and the direction we derive from them are inherently misleading.

2. Knowledge Is Dead

“What you know matters far less than what you can do with what you know,” says Tony Wagner. Because knowledge is available on every Internet-connected device, and instant answers can be found on Google, tests that focus on content knowledge—the tests most often and easily standardized— disengage and, ultimately, disadvantage students.

Look at Google’s hiring team. Why should we continue to emphasize content knowledge when employers aren’t asking for it?

“Every young person will continue to need basic knowledge, of course,” he says. “But they will need skills and motivation even more… [which are] increasingly important as many traditional careers disappear.”

But don’t count on students to stand out if they are constantly being trained to fit in.

3. You Are What You Score

In her book Now You See It, Cathy Davidson points to the similarity between standardized tests and the ‘assembly line model,’ effectively placing kids inside a one-fits-all educational mold and labeling low-scoring students as failures.

When students are already wired, as humans, to compare themselves to others, it only exacerbates the situation when their basis for comparison is designed to put some of them at a disadvantage. Standardization may enable consistent measurement, but it creates a nasty byproduct in the process: a consistently distorted self-image.

Students who ace tests internalize their performance as self-worth, and students who fail tests (and see others succeeding) internalize their performance as self-worthlessness. This trend can last throughout an entire educational career—or lack thereof.

A Harvard University study found that standardized testing actually increases the drop-out rate. Students in the bottom 10 percent of achievement were 33 percent more likely to drop out of school in states with graduation tests. The National Research Council found that low-performing elementary and secondary school students who are held back do less well academically, are much worse off socially, and are far likelier to drop out than equally weak students who are promoted.

The simple act of writing your name on a test sheet is like signing your life away.

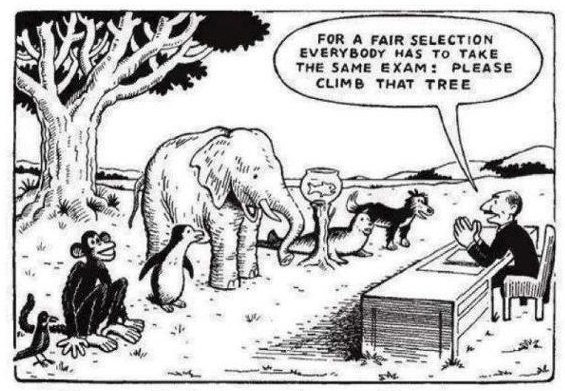

4. Ignoring The Individual

Because standardized tests are, by definition, meant to be administered, scored, and interpreted in a standardized and consistent manner, they ignore differences in student learning style and background.

This is perhaps the least remediable aspect of the tests, and for that reason the most harmful. While not all standardized tests use multiple choice questions—many are actually performance or project based—they are designed to judge all students using the same set of criteria.

And while this is completely necessary for efficient grading, it does not take into account individual variances in learning style or background, and teaches students to follow guidelines more than it teaches them to think outside the box.

5. What Not Tested Is Not Taught

Educator Alfie Kohn advises parents to ask an unusual question when a school’s test scores increase: “What did you have to sacrifice about my child’s education to raise those scores?”

As schools struggle to avoid the “underperforming” label, entire subject areas—such as music, art, social studies, and foreign languages—are de-emphasized. What is not tested does not count, and 85 percent of teachers believe that their school gives less attention to subjects that are not on the state test.

One teacher had this to say about how the timing of state tests drives teaching: “At our school, third- and fourth-grade teachers are told not to teach social studies and science until March.” As “real learning” takes a backseat to “test learning,” challenging curriculum is replaced by multiple choice materials, individualized student learning projects disappear, and in-depth exploration of subjects along with extracurricular activities are squeezed out of the curriculum.

Educator Alfie Kohn advises parents to ask an unusual question when a school’s test scores increase: “What did you have to sacrifice about my child’s education to raise those scores?”

As schools struggle to avoid the “underperforming” label, entire subject areas—such as music, art, social studies, and foreign languages—are de-emphasized. What is not tested does not count, and 85 percent of teachers believe that their school gives less attention to subjects that are not on the state test.

One teacher had this to say about how the timing of state tests drives teaching: “At our school, third- and fourth-grade teachers are told not to teach social studies and science until March.” As “real learning” takes a backseat to “test learning,” challenging curriculum is replaced by multiple choice materials, individualized student learning projects disappear, and in-depth exploration of subjects along with extracurricular activities are squeezed out of the curriculum.

6. Students As Guinea Pigs

Koretz says that while in some nations like the Netherlands, it’s routine for schools to be visited by outside inspectors who look at far more than test scores (and, in fact, the Dutch public often hears about test scores in the context of an inspector’s report), in the United States we don’t measure and tweak. We realize, in hindsight, that a policy didn’t work, leaving many classes of students behind in the process.

“What we have is a lot of interesting ideas about better ways of holding schools accountable and very little hard research,” says Koretz. “And I would say that that’s really an ethical problem, not just a political problem. It’s a political problem because we lack information that we could use to better serve children. It’s an ethical problem because children are not consenting adults. When we drop into schools these very high powered policies that clearly change teacher’s behavior in dramatic ways, we have an obligation, in my view, to monitor what happens.”

To get hired at Google, Microsoft, BBC News, Peking University, the Commonwealth Bank of Australia, St. Mary’s Hospital, the International Grocer’s Association, even the local burger joint—or to invent a new job in ten years— students need to spend more time using their skills than measuring them.