A Spectrum Of How To Create Learning Through Play

How can you teach through play?

We’ve talked before about the role of play in learning, and this is an idea that I’m becoming fascinated with. It’s also a bit of a tough nut to crack.

What exactly is play? Can you make it happen, or must you let it happen? What is the relationship between play and ‘flow’? And what does this all mean for formal and informal learning environments? Well, that depends on whether you see the role of play and self-direction in learning as necessary or a waste of efficiency.

What Students Need To Learn Through Play

Less Restrictive

1. Given nothing

The student little receives zero resources or support. They can do–or choose not to do–whatever they’d like.

2. Given time

At this stage, a student is merely restricted by some sort of time constraint. ‘Do whatever,’ you might say to the student, “But do it within this timeframe.”

3. Given playful spaces

One step more restrictive than being given either ‘nothing’ or a basic time constraint, at this level the student is ‘placed’ in a playful space–whether physical or digital. Beyond that immediate context–and the freedom to make mistakes and ‘fail forward,’ that’s really it.

4. Given opportunity for collaboration

At this stage, students are merely given the opportunity to collaborate, perhaps in a playful space. It very well may be time-constrained but that’s not necessary. Again, no other support or framing is offered.

5. Given dynamic tools

At this level, creating learning through play suggests that students be given dynamic tools to place within playful spaces with the opportunity for collaboration. No ‘content’ is delivered at this level.

6. Given a topic

One level ‘more restrictive’ than the above five levels, ‘level six’ sees students actually given content for the first time: a topic.

At this level, students are given all of the above (well, except #1), but also offered a topic: gravity, variables, symbolism, war, hip-hop, etc. No further criteria or suggestion is offered. No test is given and as usual, the above options of time, spaces, collaboration, and tools are optional. By giving students an actual topic, students still don’t have an ‘assignment’ but they have a specific morsel of some kind to begin with.

7. Given engaging models

Want to create learning through play but don’t want the learning purely open-ended and curiosity-based? This level begins to apply actual ‘models’ or suggestions. (Whether this helps or diminishes the quality of student work and learning obviously depends.) Regardless, students now have added in their ‘learning space’ engaging exemplars of human thought: paintings, apps, novels, architecture, music, examples of math-as-problem-solving-tool, etc.

8. Given a challenge or goal

Let’s add one more twist of the crank and get a bit more specific: Give them a specific challenge or goal. Examples? Solve this problem. Make 10 shots in a row. Find a more efficient way to package an item. This sort of ‘goal’ or challenge should be relatively minor or it could quickly become a full-blown project.

9. Given a process, learning model, or cognitive framework

At this point, the learning process becomes significantly more restricted. Students are given a process, sequence, framework, or some other external method that acts as both ‘support’ and a detriment to their own natural self-direction.

10. Mandating collaboration with little choice

Added to the above externally-planned sequence, learners are now required to collaborate, with little choice with whom, for what purpose, and at what stage of the learning and/or production/design process. This is a far cry from the early stages of creating learning through play where students were simply given spaces or time or ideas. Now, teachers are actually requiring specific collaboration with specific requirements and little choice–at least about the collaboration itself.

11. Given specific criteria

In addition to deciding the space, topic, models, challenges, and collaboration, the teacher (or expert) now also adds specific criteria to the assignment, whether this is basic (a due-date), moderate (number of resources required), or more complex (specific criteria of a specific model to be produced by the learner).

12. Given a flexible rubric

The teacher helps guide the learner in understanding what might determine the ‘quality’ of an assignment. This can be both supportive or restrictive, depending on how it’s done.

13. Given an assignment

The teacher has taken the task of deciding content, form, and criteria to create and/or distribute an ‘assignment’ that is hoped to lead to a specific understanding. The level of support/restriction is becoming significant.

14. Given a detailed project with a detailed rubric

The students here may have the flexibility of a project, but everything else is dictated and externally directed.

15. Given fully scripted assignments packaged as a unit of student or project

This is among the most restrictive approaches to learning (though that doesn’t have to mean it’s ‘bad’–it’s simply restrictive, which generally has the effect of diminishing the opportunities for learning through play.

Depending on your perspective, this is either expertly planned by a trained teacher to produce creative and critical thinking learners that can self-direct their own learning pathways. or it is stifling to those same areas, eroding learner self-direction, innovation, play, and, further, educator capacity.

Less Restrictive

Both flow and play require a strong sense of volition and intellectual safety on the part of users. Self-directed learning, project-based learning, mobile learning, and other 21st-century learning forms all rely heavily on the states of mind.

It also seems that play precedes flow to some extent–and since each is a powerful resource for imagination, creativity, and innovation, it makes sense that we understand where they come from and how they work.

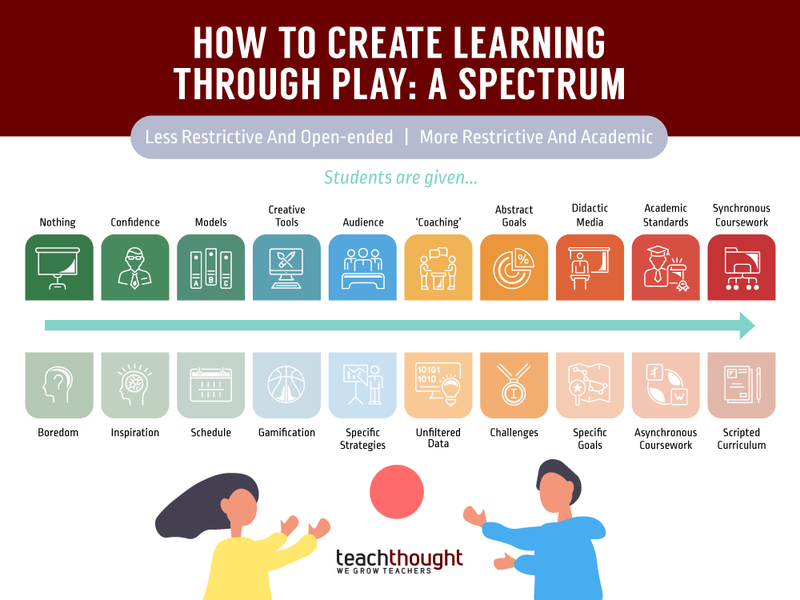

In pursuit, I put together the above draft of a play ‘spectrum’ to give an idea of what it looks like compared to traditional learning. It moves from less to more restrictive top to bottom, where learners are given ‘nothing’ in a completely unrestricted environment–literally nothing–and given specific assignments with detailed rubrics in a more restrictive environment.

In the middle is a kind of sweet spot, where learners are simply given dynamic tools, opportunity for collaboration, and the ability to work and produce free from critical judgment. Other components are also available, from engaging models and peer-to-peer collaboration to browsing tools and available audiences.

The end result would be a learning environment where learners are empowered to experiment, interact, solve problems, fail, share, iterate, and self-direct. The spectrum above essentially creates a range of conditions that are more or less likely to create play through learning–and learning through play.

How To Teach Through Play: A Spectrum