How To Prepare Students For A Modern Economy

by Terry Heick

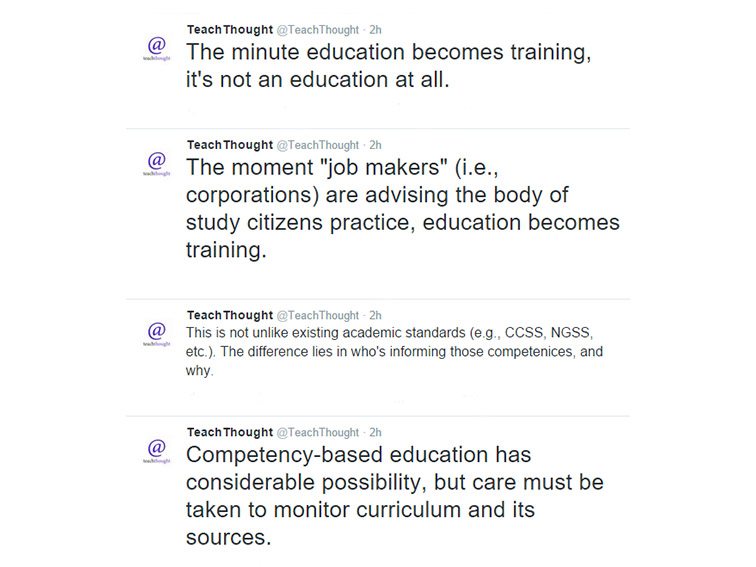

Doing some reading (and listening) on competency-based education recently, I was both intrigued and concerned.

The concern came recently after listening to a higher ed chancellor celebrate the source of his university’s curriculum. It was during a panel discussion on Competency Based Learning, where he explained the research for the prioritized competencies began with “federal skills databases.”

This sounds innocent enough. Even efficient. Among the benefits of this approach? Less “educational waste.” Learn the skills that companies want you to have. Produce more “hire-able” graduates. Slow the production of “employees” with $60,000 in debt while working retail and fast food and drowning in debt.

It’s difficult to argue against precise curriculum that produces graduates that can better support themselves in a modern economy. The difficulty lies in the terms–who creates them, and the language used as their description.

The Characteristics Of Competency-Based Education

Competency-based education is individualized–or should be. The focus is on students mastering given competencies. It’s clear, adjustable for unique student needs, and efficient. Characteristics of competency-based education include:

- Competency-based education is no longer time-bound: Focus on mastery rather than time; asynchronous

- Competency-based education makes it simpler to prioritize specific content.

- Competency-based education reduces “curriculum clutter.”

- Competency-based education values performance-based assessments over more academic forms (e.g., multiple choice exams).

- Mastery is valued over grades (which is hard to argue against)

Deb Everhart at Blackboard explains.

“The pressure to make higher education more accessible and affordable also comes at a time when there is a huge mismatch between what employers need and what traditional education is providing. A recent Lumina Foundation/Gallup study yielded this startling finding: 96% of chief academic officers rate their institutions as effective in preparing students for the world of work, while only 14% of Americans agree, and only 11% of business leaders agree that graduates have the skills and competencies their businesses need.

And it’s not just a difference of opinion. Even in this time of stubborn unemployment, 40% of U.S. employers report difficulty in filling jobs due to a lack of applicants with appropriate skills, with the talent shortage most acute in skilled trades. More than half of employers state that this gap has a significant impact on their businesses.”

The American Enterprise Institute is even more direct, advising that “Institutions offering CBE programs should partner closely with employers to help students attain the general and specific skills they need to succeed in the labor market.”

And I get it. When universities graduate students with “non-marketable skills,” that’s a problem. The caricature here is the Humanities graduate working retail or fast food (maybe both), while the MBAs run the world. The goal of K-12 can’t be “career prep.” But what about college? Isn’t that the point of college–to hone generalized knowledge into something “useful”?

Errr, kind of.

There is some frustration, and even loss, in gathering seemingly loosely connected skills and understandings (from the various classes in a traditional undergraduate program) into a credible, hire-able aesthetic employers will respond to when the students become employees. Yes, you could have Apple, Uber, Amazon, and Ford “collaborate” on a “curriculum” that would produce–like a widget-filled conveyor belt–employees ready to make those companies some dough.

But schools don’t graduate employees, they graduate human beings. And just as universities haven’t been “job training facilities,” more immediately, neither has K-12. The rub comes when universities seek to revise themselves. The more connected K-12 is to university goals and aspirations, the more K-12 is on the hook here as well to “tighten the curriculum” to make it “more efficient.”

To straighten and shorten the path from student to “job.”

Jobs Are Gross; Work Is Love

A job is to work as a single instrument is to a symphony.

A job is a single episode of Seinfeld in a 9 year run.

A job is a mold that a person either fits or does not.

A job is granular; one’s life’s work is whole.

The “loss” embedded within a Humanities or Engineering degree is only a loss judged by the mold itself. The person entering the mold will likely leave it again, and that previous loss can be re-evaluated.

Jobs are gross–at times necessary, but mostly molds created by industry that dehumanize people while doing untold damage to communities, ecologies, and fundamental human aspiration. They stunt the vision a person might have to create a life, and make their work a part of it. Their episodic nature stifles intellectual momentum, and a sense of self.

Work is different. Work is what a person bears upon the world with their own hands, with creativity, vision, and affection. Work is love–natural extensions of the person in their native place. Education should, at least in part, prepare students for that. But in thinking like this, we’re lowering our sights from person and place to job and market. When we seek to train students, we have to ask ourselves what we’re training them for, and make sure we can live with the consequences.

Competency-based education doesn’t demand narrow job training, but it is absolutely a shift from people to companies. So where’s the light here? Consider a different scale; the best education will transcend notions of job and career and profession and work; it will prepare students for any of these scenarios and more, while requiring none to inform their design.

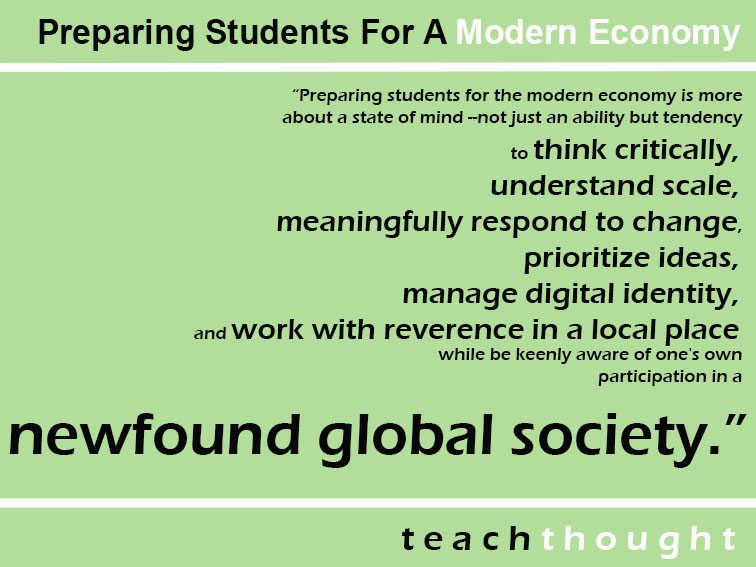

Preparing students for the modern economy isn’t about streamlining job-training, especially for jobs that will not only change often, but disappear more quickly than any generation in history. Skills matter, but preparing students for the modern economy is more about a state of mind–one that can, among other tendencies, think critically, understand scale, meaningfully respond to change, prioritize ideas, manage digital identity, and work with reverence in a local place while being keenly aware of one’s own participation in a newfound global society.