Why Should Schools Teach Digital Literacy?

by Terry Heick

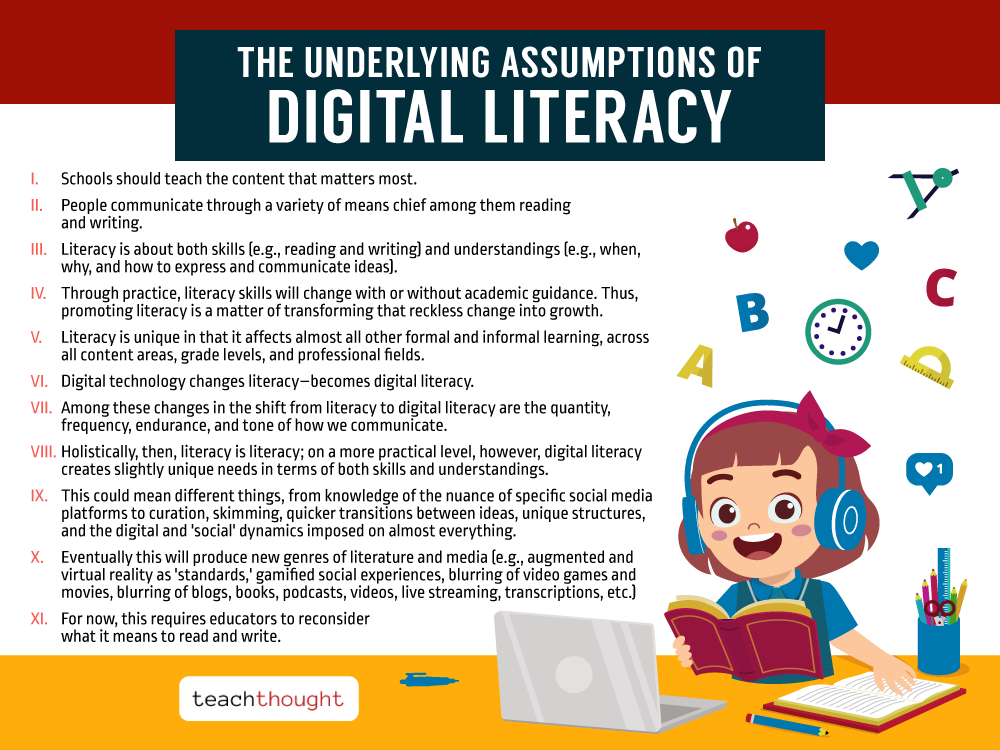

In understanding the shift from literacy to digital literacy–or rather to understand them both in their own native contexts–it may help to take a look at the underlying assumptions of digital literacy.

This means looking at what’s changing, why it’s changing, and what that means for education.

1. Schools should teach the content that matters most.

Put another way: We should promote the cognitive growth of the kinds of ‘things’ that help people make their lives better.

2. People communicate through a variety of means chief among them reading and writing.

Put another way: Reading and writing are common and critical.

3. Literacy is about both skills (e.g., reading and writing) and understandings (e.g., when, why, and how to express and communicate ideas).

Put another way: Literacy isn’t any one thing, but rather represents a person’s ability and tendency to communicate and be communicated to.

4. Through practice, literacy skills will change with or without academic guidance. Thus, promoting literacy is a matter of transforming that reckless change to growth.

Put another way: Through practice, media users will, for better or for worse, ‘get better’ at communicating through technology. Through analysis, planning, modeling, scaffolding, and practice of our own, as educators we can facilitate more strategic growth.

See also The Underlying Assumptions Of A Curriculum

5. Literacy is unique in that it affects almost all other formal and informal learning, across all content areas, grade levels, and professional fields.

Put another way: Literacy is foundational.

6. Digital technology changes literacy–becomes digital literacy.

Put another way: Technology isn’t just about connecting; ideas are like fluid, adapting to the vessels that hold them. Reading is reading and writing is writing but publishing that writing or accessing that reading is context-dependent.

7. Among these changes in the shift from literacy to digital literacy are the quantity, frequency, endurance, and tone of how we communicate.

Put another way: Abundance changes everything. When you can communicate almost any thought anytime, anywhere, things change. (See screen addictions, whimsy, snark, cyber-bullying, passive aggressiveness, skimming-abuse, inability to focus, changed personal values/sources of dopamine/self-worth, devaluing of quality data and content, and other effects of this abundance.)

8. Holistically, then, literacy is literacy; on a more practical level, however, digital literacy creates slightly unique needs in terms of both skills and understandings.

Put another way: If literacy is different, what developing readers and writers need to know is different.

9. This could mean a lot of different things, from knowledge of the nuance of social media platforms to acronyms (e.g., ‘lol’), to quicker transitions between ideas (e.g., constant deluge of suggested ‘content’), to unique text structures (e.g., shorter paragraphs) and sentence structure (i.e., generally simpler), to social ‘dynamics’ imposed on almost everything.

Put another way: Media literacy (which isn’t a new concept) is part of digital literacy and it’s all complicated and only going to get more so.

10. Eventually this will produce new genres of literature and media (e.g., augmented and virtual reality as ‘standards,’ gamified social experiences, blurring of video games and movies, blurring of blogs, books, podcasts, videos, live streaming, transcriptions, etc.)

Put another way: See #7.

11. For now, this requires we as educators to reconsider what it means to read and write.

11 Underlying Assumptions Of Digital Literacy