Differentiated Instruction: A Definition For Teachers

For teachers and administrators, a useful definition of differentiated instruction is “adapting content, process, or product” according to a specific student’s “readiness, interest, and learning profile.”

It can be first that of as a matter of contrast–‘differences.’ This student needs something different than that in pursuit of a given learning goal.

We’re not sure it is a matter of fact how personalized learning, personal learning, and differentiated instruction compare, but we tend to think of differentiated instruction as the process of optimizing the packaging of academic content for individual students, while the former ‘personalized’ and ‘personal’ learning can also involve the changing of the content itself.

That is, this student needs to learn this content, while differentiation is a matter of tailoring teaching for each student to reach the same content.

In the context of creating instruction that actually meets learners “where they are,” differentiated instruction is a bit of a pioneer. Like Grant Wiggins’ work with backward-planning, and Robert Marzano’s focus on research-based strategies, differentiation has had champions of its own, and among the leaders of that niche in teaching is Carol Ann Tomlinson, Chair of Educational Leadership, Foundations, and Policy at the Curry School of Education at the University of Virginia.

Tomlinson has published extensively with ASCD on the topic of differentiation (including a book that discussed differentiation in the context of Wiggin’s UbD), where the goal for differentiated instruction was given:

“The goal of a differentiated classroom is maximum student growth and individual success. As schools now exist, our goal is often to bring everyone to “grade level” or to ensure that everyone masters a prescribed set of skills in a specified length of time. We then measure everyone’s progress only against a predetermined standard. Such a goal is sometimes appropriate, and understanding where a child’s learning is relative to a benchmark can be useful.

However, when an entire class moves forward to study new skills and concepts without any individual adjustments in time or support, some students are doomed to fail. Similarly, classrooms typically contain some students who can demonstrate mastery of grade-level skills and material to be understood before the school year begins—or who could do so in a fraction of the time we would spend “teaching” them.

These learners often receive an A, but that mark is more an acknowledgment of their advanced starting point relative to grade-level expectations than a reflection of serious personal growth. In a differentiated classroom, the teacher uses grade-level benchmarks as one tool for charting a child’s learning path. However, the teacher also carefully charts individual growth. Personal success is measured, at least in part, on individual growth from the learner’s starting point—whatever that might be.”

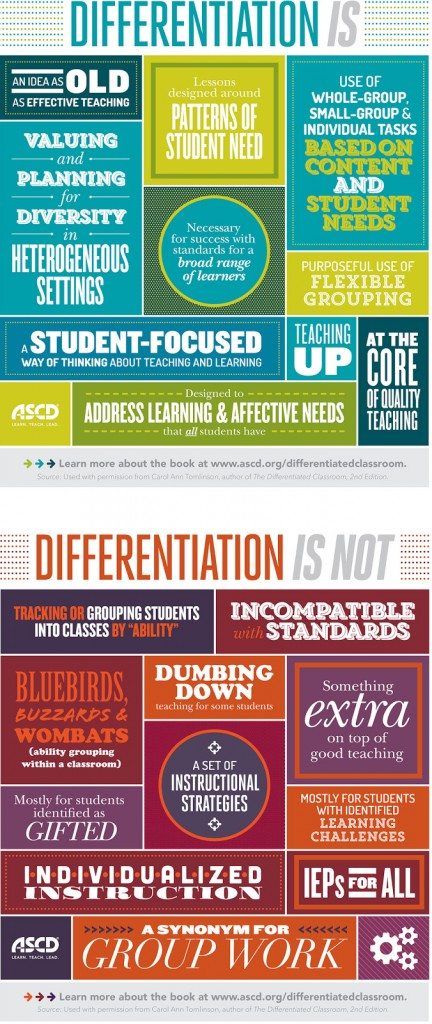

The following graphic from ASCD offers several examples of what differentiated instruction is–and is not. The information here comes from Carol Ann Tomlinson’s newest book,The Differentiated Classroom: Responding to the Needs of All Learners, 2nd Edition.

What Differentiated Instruction Is–And Is Not: The Definition Of Differentiated Instruction