What Are The Best Strategies For Teaching Students To Listen Actively?

Active listening involves employing different behaviors to enhance understanding among two or more people in a conversation.

An active listener is present in the conversation. They hear the speaker’s words and pay attention to their body language in order to make connections. The brain is engaged, picking up on overarching themes or repeated phrases that indicate the essence of a speaker’s message. The fewer people engaged in a conversation, the more difficult it is to feign active listening.

Such a skill is particularly important for 21st-century learners. In an age of information overload and distractions galore, some may find it more difficult to sustain attention during a conversation. Active listening conveys empathy and understanding. It builds trust and confidence. It signals that the listener cares about the speaker and/or their message.

Active listening is, perhaps, the foundation to a successful Socratic Seminar, Fishbowl conversation, or round of Philosophical Chairs. Beyond class discussions, active listening is essential for assignments and activities that require students to read, listen to podcasts, interview subjects, provide peer feedback, and participate in restorative justice sessions.

We can set up a dichotomy between active and passive listening–it’s (mostly) obvious when someone is feigning interest, mildly distracted, or totally checked out of a conversation. Teachers and students alike can tell, when they are speaking, if someone is annoyed, preoccupied, or bored.

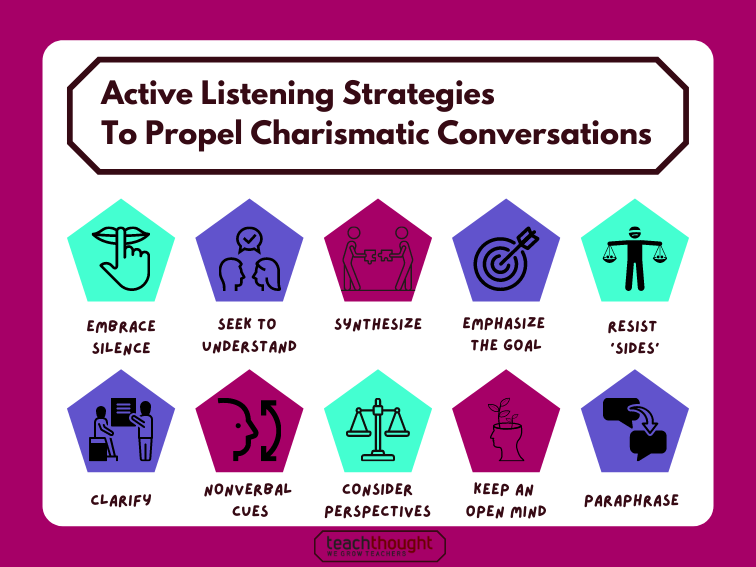

As teachers incorporate more elements of collaborative learning in their lesson plans, it is critical that they model active listening to their students. Modeling active listening is just as important at the high school level as it is at the elementary level–educators should never assume that their students are practiced in these seemingly simple skills. Below, we’ve listed ten strategies to model for students in order to improve their active listening skills. Students should have multiple opportunities to practice these skills, and we’ve included some ideas for how teachers can model each strategy. If any readers have used activities that we haven’t listed, we’d love to hear them.

10 Active Listening Strategies To Propel Charismatic Conversations Among Students (And Teachers!)

(1) Use affirming facial cues, body language, gestures, and nonverbal signs

With active listening, the listener is physically oriented toward the person speaking. Whether sitting or standing, the listener faces their body toward the person speaking. Their eye contact is focused on the speaker, instead of on other distractions or priorities. An active listener’s posture is upright and engaged, versus slouched or withdrawn. One way that we teach this most basic active listening skill is by pairing students up and posing a question, such as, “What was the most meaningful moment of your life?” “What do you look for in a friend?” “Describe your favorite vacation and explain what made it great.” Depending on the bond between the students, you may want to ask more low-stakes questions for less-familiar students, who may be hesitant to show vulnerability with a new peer. After you’ve given the pairs some time to think about their response, you then share that the first person will have an entire minute to share their answer, while the second person can only listen and communicate using their body. After a minute, they switch roles. In this minute, the listener can nod, raise their eyebrows, lean forward, clasp their hands, smile…but they cannot speak. It is quite entertaining to watch the listeners, on the one hand, struggle with not being able to chime in with their own experience–but that’s exactly the point. Forcing them to refrain from speaking helps them focus on the behaviors they can employ to show empathy and understanding. On the other hand, more reticent speakers may struggle with filling an entire minute with speech. This struggle brings us to our next strategy.

(2) Embrace silence

Ahh, silence…usually paired with the adjective ‘awkward,’ silence in a conversation is where the magic really happens. Just because someone is not speaking doesn’t mean that they aren’t thinking. Silence is often an indicator of thought processing, metacognition, and introspection. In an activity like the one we just described, there is bound to be silence in the first round or two of practicing active listening. It may be wise for teachers to–after the first round–ask them how they felt about the silence. Did it make them feel anxious? Did it make the speaker feel frozen? Did it make the listener want to fill the gap? What is it about silence that makes us feel awkward? These are questions worth pondering. In the second round of the activity we’ve described, the teacher can direct the students to pay attention to the moments of silence in the conversation. The listener might consider why it is difficult for the speaker to continue elaborating or sharing. What might be holding them back? Fear? Distrust? Lack of experience or opinion? These kinds of considerations are the (literal) unspoken factors in a dialogue that can communicate volumes. Challenge the listeners within the pairs to amplify their nonverbal skills, depending on why they think the speaker is silent. This could be a time to maintain eye contact, offer a knowing glance, or give an encouraging nod.

(3) Summarize or paraphrase the speaker’s statements back to them using key words

Once students have gotten more comfortable with using their nonverbal communication skills, teachers can offer up a new prompt to discuss and a new challenge for the listeners. In this round, the listeners are able to speak. “Yippee!” they will surely scream…but not so fast! The focus is still on the speaker. This time, the only time the listener can speak is to paraphrase the speaker’s statements back to them. Paraphrasing is different than simply repeating what the speaker said, word for word. It involves paying attention to certain words that the speaker touches on in order to discern a theme. Based on the speaker’s language, what did an experience mean to them? How do they feel about a particular topic? What reasoning do they use to justify their actions? The paraphrasing does not have to occur at the end of the sixty-second round–the listener can paraphrase throughout the minute. The teacher may even double the speaker’s talking time in order to allow for more meaningful dialogue. Paraphrasing can be an incredibly powerful tool. It is a way to show that we are paying attention, that we care, that what the speaker is saying is important and we value their experiences and emotions. Each student should get several rounds of practice with this critical skill, which is essential for any job or relationship in the so-called ‘real world.’

(4) Ask probing or clarifying questions

Students who have had sufficient practice with paraphrasing the speaker’s words back to them can build upon their active listening skills by asking questions meant to clarify or prompt the speaker to elaborate. Truly another form of paraphrasing, asking questions demonstrates that the listener has attempted to process the sensory data they’ve received and are now intent on filling in the gaps. Asking questions is a way to participate in a conversation without dominating. In the next round of active listening practice, the teacher might ask a new question of the speaker, then inform the listeners that they are now allowed to ask questions. Ideally, they will ask open-ended questions meant to elicit more than a simple yes/no answer; that being said, yes/no questions certainly aren’t off limits! It is important that the teacher model this process. Depending on the nature of the prompt, it might be helpful for the instructor to offer sentence stems to the listeners. For example, let’s say the question for this round is, “What role do you play in your family?” Examples of sentence stems to respond to the speaker might include: “What makes you feel that way?” “How do you know?” “What do you like about your role?” “How would you like to change your role?” These questions compel the speaker to think more deeply about their response while conveying that the listener is paying attention and genuinely curious about the response.

(5) Acknowledge (or better yet, synthesize) a previous point before sharing your thoughts

Now it’s time to take the listening process a step further. In this next round of dialogue, the pairs can continue, or the teacher can combine two dyads to form a group of four. More participants means more information and emotion to absorb, which can be more challenging for students who are new to active listening. Regardless of student combinations, the next level of active listening challenges students to be both speakers and listeners at the same time. The one caveat is that–before sharing their own thoughts–each student must acknowledge a previous point first. Sentence stems are definitely useful in this round. Stems like “I understand how…” and “when you said…” and “I agree with” are a few helpful examples. By acknowledging the previous speaker’s point, the new speaker demonstrates that they are not merely chomping at the bit to share their own input. It shows that they take the previous speaker’s message into consideration and synthesize it with their own opinions, beliefs, or experiences, before speaking up.

(6) Seek first to understand, then to be understood

Readers may recognize this strategy, as it’s one of Stephen Covey’s 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. In fact, Dr. Covey considers this habit to be the most important principle he has learned in interpersonal communication. After practicing in a group of four, the instructor can then combine two groups into a large group of eight. Obviously, a minimum of five minutes is needed for a larger conversation. One strategy we’ve talked about before at TeachThought is the 3 Before Me strategy, where the student must seek input from three other students before asking for help from the teacher. We’re going to adjust that strategy for active listening practice, and stipulate that any one participant in the group must wait until at least three different people have spoken until they make another contribution. This strategy can be especially helpful before engaging students in a larger group discussion, like a Socratic Seminar. Many times, those who are new to student-driven conversations are so concerned with getting a good grade on a discussion-based assignment that they just spout off whatever statements they prepared without acknowledging the previous point. This kind of behavior often leads to a confusing, disjointed conversation, in which there is little synthesis of ideas. By implementing the revised 3 Before Me strategy, the student is challenged to truly hear, absorb, and synthesize what the other group members are sharing before making their own statement.

(7) Emphasize and refer back to the goal of the conversation

Speaking of disjointed conversations, it’s natural for students to veer off track in a larger group discussion. In these cases, the teacher (who is meant to serve as the facilitator) may feel compelled to pause or interrupt the conversation. Instead, we suggest using visual cues to remind students of the conversation purpose. One way of doing this is for the teacher to point to a verbal reminder displayed on the whiteboard. Ideally, the teacher can challenge the students to monitor themselves. Perhaps they can come up with an unobtrusive hand signal–since they will be facing each other in a student-led dialogue, it makes more sense for the students to remind each other without the teacher diverting attention away from the conversation. Of course, all of this is predicated on the notion that the instructor or group of students establish a purpose of conversation in the first place. The purpose can come in the form of a statement or an essential question, such as: “What can schools do to improve the learning experience for students?” We speak from experience when we say that many students may want to share personal anecdotes regarding teachers they dislike, subjects they despise, or times when they felt a sense of injustice. In these cases, students run the risk of veering off-topic from the purpose of the conversation. It’s not that their experiences aren’t valid or relevant, but perhaps the students aren’t taking their contributions a step further by offering a solution for avoiding the things about school that don’t work for them.

(8) Resist ‘sides’ and insist on both critical thinking and empathy

One way to generate substantial student dialogue is to ask relevant–hough possibly controversial–questions. These could be questions that relate to social, cultural, political, or economic ideas, such as: “How should we interpret the 2nd Amendment of the United States Constitution in the 21st Century?” or “Why are vaccine/mask mandates a good or bad idea?” or “What is considered ‘hate speech’ and to what extent should it be censored or not?” These are popular topics in today’s digital and physical society, and students may be eager to share their beliefs. On the flip side, students may also be more resistant to opposing ideas. That being said, if we are intent on producing actual solutions in the real world, we know that involves compromise and a merging of values. One idea to give students practice in resisting sides is to challenge them to take on the stance that opposes their personal beliefs. Teachers may be met with an onslaught of groans and protests, but they can then emphasize the purpose of the conversation (which, in this case, is to develop empathy and critical thinking skills). Naturally, students may need more time to prepare for these conversations–to research opposing viewpoints, gather data, and seek anecdotal evidence. How does this all help with active listening? By having to research the opposing viewpoint, the students are essentially priming themselves to receive information that counters their own experiences.

(9) Consider diverse perspectives and experiences

Considering different perspectives is different from resisting sides. While resisting involves preventing a type of behavior, considering involves welcoming a type of behavior. Resisting sides involves staying close to neutrality while considering diverse perspectives involves considering everything that exists outside of neutrality. In 50 Everyday Formative Assessment Strategies, we detail an activity called Ongoing Conversations, where students receive a piece of paper with a 2-column chart. In the left column are enough spaces for each student in the class; on the right side is an empty box large enough for a person to write 1-3 sentences. The teacher can ask a question or issue a prompt, and the students then have a given amount of time to discuss the question or prompt with a new partner. They summarize their partners’ responses in the right column next to that partner’s name. The challenge is for each student to talk to a brand new person in class before talking to one person twice. This is a great activity for classes where students tend to gravitate toward the same partners. It can also be useful as a means of ‘breaking the ice’ before a potentially intense conversation. Actively listening to (and summarizing) one response at a time can prime the student for what they might hear in a larger group discussion. Because all students have spoken to each other, and hopefully listened with intent, there is less pressure to insist on the validity of one’s own beliefs and more focus on empathy and critical thinking.

(10) Keep an open mind

There are many similarities between our last two active listening strategies. Considering diverse perspectives is representative of open-mindedness. What we want to emphasize here is how the body can ‘shut the mind off’ from receiving information that isn’t compatible with our well-established beliefs. With a young, impassioned group of students, it is likely that some may become upset, frustrated, sad, or even afraid in a more controversial conversation. When our sympathetic nervous systems are highly activated (aka, we are ”triggered’), we may go into fight, flight, or freeze mode. This involves a biological reaction in which the body prepares to go on the offensive, shut down, or run away. When we are on high alert, we may not be receptive to listening with empathy. We may not prioritize the importance of critical thinking. Something that was said or communicated nonverbally signals to us that we are in danger or that we are being judged. It may be helpful for the instructor to lead a class in mindful breathing techniques if they know that a conversation has the potential to get intense. In How Can You Teach Mindfulness To Your Students? we offer ten tips for helping students to practice patience, transfer, and using their imagination to maintain equilibrium of the nervous system. Prior to engaging in a large group discussion, it may be useful to teach students how to recognize when their own nervous system energy is increasing, as well as when others are getting worked up. It’s not that we necessarily want to prevent these spikes in energy–being able to recognize them and manage them can help us stay receptive. Not only are we learning how to actively listen to others, but we can actively listen to our own bodies.