Why Study Skills Classes Matter Now More Than Ever

Why Study Skills Classes Matter Now More Than Ever

by Jane Healey, Ph.D.

A recent article in the Chronicle for Higher Education addressed the Freshman Seminar experience and applauded the high ideals while reporting on the “mixed results.”

The issue is an aged-old quandary: schools want entering students to collectively learn the necessary skills for their academic journey, but measuring the effectiveness of those courses is complex. How do we know if an entry-level course meant to provide basic instruction for success in other classes works? The variables and slippery nature of measuring skills (not content) requires a creative approach for judging success.

I teach at an independent school that emphasizes inquiry-based learning throughout the four years of curriculum. To support that goal, students enroll in a freshman course to learn about teachers’ expectations and ways to meet those goals. I can imagine the eyebrow raising, eye rolling and cynical nodding about the traditional “study skills” class that teachers and students abhor.

Let me explain.

We designed a course about critical thinking and research. Many current commentaries suggest that while educators celebrate the significance of critical thinking, we assume students know what we mean when we instruct them. We think critically without recognizing how we do so just like a basketball player completes the crossover dribble without thinking—after she learned it and practiced it for several years. We decided to slow down and break the process down: teach students what “critical thinking” means and how to do it along with having them practice it.

The materials in the freshman course teach the students thinking routines that they experiment with to develop effective habits for framing challenges in ways that can be conquered. We move from thinking into questions that matter and the best ways to ask them. (The QFT, mentioned in many posts on this site figures prominently in this stage.) The rest of the work focuses on answering questions, primarily through research of all kinds—interviews, surveys, archives, and more.

Recently, I shared the curriculum with other faculty, and I expressed the ultimate goal of the first-year course: to elevate the intellectual conversations for freshman across the disciplines. Afterwards, an administrator asked me how we’ll know if the course succeeded. The Chronicle seemed to suggest we can’t know if these courses work, and we must accept that reality. I think that as professionals, we recognize the effectiveness of those classes though we may not tie what we witness to that skills-based curriculum.

Study Skills Classes In Action

When colleagues adopt a protocol or method from an entry-level class in their own courses—regardless of discipline—I consider the freshman curriculum successful.

We know that interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary content helps to reinforce the material in students’ memories, and thus they learn it better. The same must be true of skills. When teachers reinforce an exercise or practice from the 9th grade course in other 9th grade classes, the students must be learning it better than if that bridge doesn’t exist.

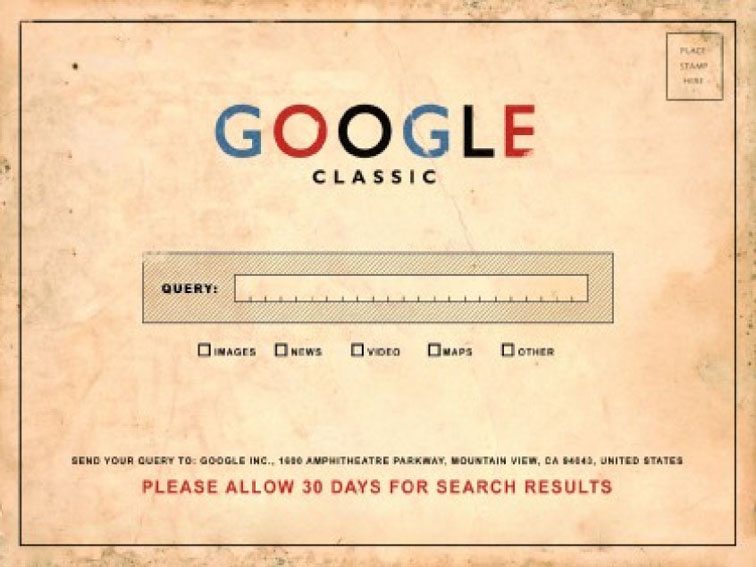

Further, if the method teaches question formulation or a thinking routine, the students will learn to craft better questions and think more critically. For example, during recent faculty meetings, a member of our team demonstrated the QFT with her colleagues using a phrase meant to start a conversation about research options: “Google is great.”

She ran through the protocol of brainstorming, examining open and closed questions, and prioritizing. Watching my peers earnestly engage in the activity was rewarding; listening to stories of successful uses in biology and history was truly meaningful.

Many “entry-level” skills-based courses live outside of the subject matter courses. They move on a parallel track that doesn’t connect to the activities of other classes. Teaching skills without content is difficult enough, but teaching skills without content and without addressing traditional “core” courses makes the novice student an alien entity.

Many schools try to link skills in these courses to material in subjects, but collaboration between teachers is difficult in already busy schedules. The research focus of our 9th grade course is the perfect invitation to traditional classes to come and play. In the fall, a biology unit requires the freshman to find answers to questions through research in credible sources. While the students work in the biology time period on the questions and answers, they work on credibility and citations in the freshman course. The work in the skills class directly impacts the success of the project in the content class.

In the spring, World History teachers expand the research realm with multiple types of sources, meaning a less focused search and potentially a wild set of results. But again, in the freshman seminar the students learn how to find a range of sources from academic search engines—not Google—how to evaluate the materials, and how to use footnotes, endnotes and a bibliography. With such specific assignments, the world history teachers can cede more control to the skills teachers who email questions or send students to the class with questions.

The success of these two examples has prompted other departments like modern and classical languages to link up with the research curriculum as a means of helping the teachers who aren’t experts in searching and evaluating. When departments open their curriculum to a skills team seeking a partnership—not vice versa—most educators would consider the collaboration a success.

Finding Teachers

Staffing freshman courses devoted to learning skills is usually an awful task. The course typically lands in the learning support arena where teachers who didn’t create the curriculum and don’t teach subject areas are forced to tackle freshmen who label the material as “not a real class.” Thus, study skills classes suffer from lethargy on both sides of the desks.

What if teachers of subject matter asked to teach in the entry-level course?

The examples of collaboration above free up the teacher from needing to cover search engines and citations—the bane of most teachers’ year—and reap volunteers from subject area faculty to play a role on the 9th grade team. Currently, two learning support teachers, a history teacher and a Latin teacher comprise the course staff. Ideally, cycling content teachers through the skills course produces organic communication with faculty as well as includes their expertise to hone the curriculum with feedback and energy.

While not every school emphasizes research as much as this one, the task will become essential to the role of education in general. Information is ubiquitous to students these days, so more and more teachers need to shift into the job of guiding students to search, evaluate, analyze, organize and share.

Housing the responsibility in a 9th grade seminar staffed with some content teachers using methods practiced by colleagues throughout the curriculum will enrich students, teachers and schools. That seems like a success no matter how we measure it.

Image attribution flickr user dotmatchbox; Why Study Skills Classes Matter Now More Than Ever