What Are The Best Strategies To Promote Curiosity In Learning?

by Terry Heick

Curiosity is crucial to learning.

For years, education has responded by admonishing teachers to ‘engaged’ students with ‘engaging content,’ but engagement and curiosity are decidedly different. An engaged student may very well be curious, but such curiosity isn’t necessary for engagement. Engagement is more than paying attention but doesn’t demand an empowered thinker forging into new ideas with an open-mind through inquiry and questioning.

That’s curiosity.

In 8 Strategies To Help Students Ask Great Questions, Terry Heick said:

“Questions can be extraordinary learning tools. A good question can open minds, shift paradigms, and force the uncomfortable but transformational cognitive dissonance that can help create thinkers. In education, we tend to value a student’s ability to answer our questions. But what might be more important is their ability to ask their own great questions–and more critically, their willingness to do so.”

Where Curiosity Comes From

The stages of curiosity come from the learner in an inside-out pattern.

This is a crucial distinction; It means it doesn’t happen by dangling flashing, singing, and dancing carrots in front of students. Rather, curiosity stems from past experience and current knowledge, then leaps out as the neocortex seeks patterns it recognizes, then rewards itself with dopamine when it finds something it either understands or seeks to understand, branching out to new domains, applications, and opportunities for transfer.

“A good question can…force the uncomfortable but transformational cognitive dissonance that can help create thinkers.”

But how does one ’cause’ curiosity? This is the challenge of instructional design, lesson design, curriculum mapping, project-based learning templates, and a thousand other factors.

Any modern movement in progressive learning systems should at the absolute minimum be aware of what tends and does not to tend to stimulate curiosity, and how its surplus and absence can affect the learning experience overall. Curiosity can be seen as part of the student themselves rather than a kind of ‘brain emotion’: the student, their unique curiosities, and their patterns of self-direction as they seek to understand things because their brain wants to understand.

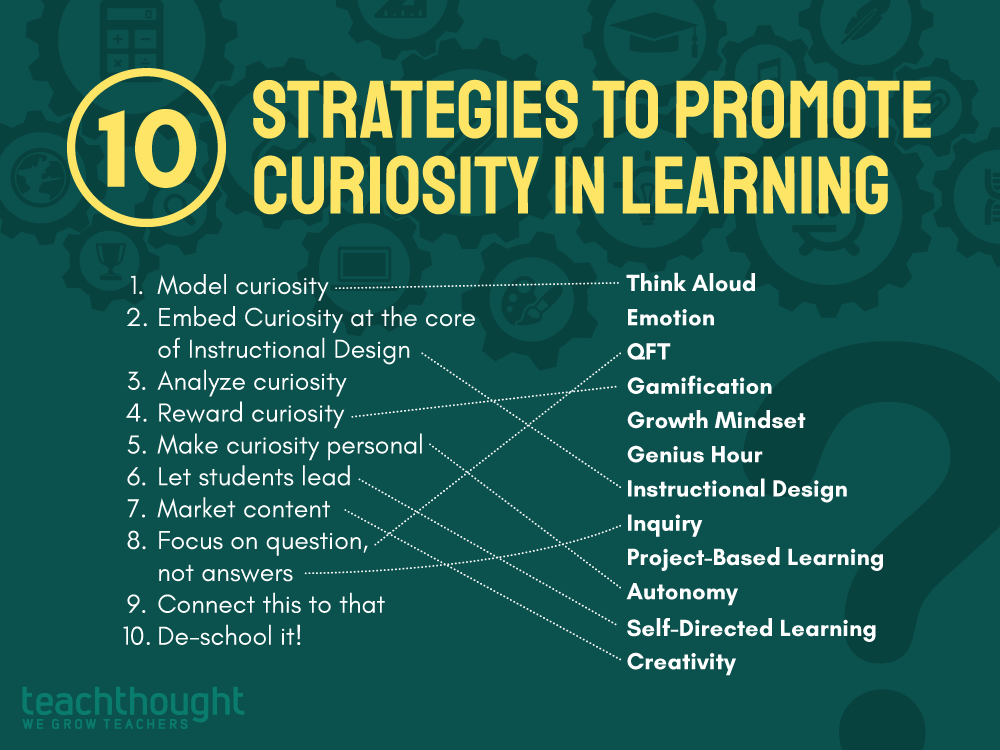

10 Strategies To Promote Curiosity In Learning

1. Model curiosity in its many forms.

Curiosity is a human instinct but like most instincts, it can be refined through observation and practice.

Example: Think-aloud while reading an illustrated picture book, watching a video, or even having a conversation. As long as you can ‘pause’ to ‘think out loud,’ you can explain how and what and why you’re thinking what you’re thinking, questions you have, things that pique your interest—and most crucially, the courage to follow that curiosity wherever it takes you.

2. Embed curiosity at the core of the instructional design process.

Example: An inquiry-based learning unit in which the lessons and activities ‘don’t work’ without curiosity. One example could be a QFT session.

3. Analyze curiosity. Help students see its parts or understand its causes and effects.

Example: Consider using the TeachThought Learning Taxonomy in designing these sorts of tasks.

4. Reward curiosity. If you want a plant to grow, you feed it. Curiosity is the same.

Example: Gamification is one approach. While not intrinsically motivating, one under-appreciated effect of gamification is visibility. By identifying desired outcomes and visualizing progress and achievement towards those outcomes, those desired outcomes–including curiosity–can be developed and enhanced.

See How Gamification Uncovers Nuance In The Learning Process

5. Make curiosity personal.

Example: Require students to choose a topic for an essay, then refine that topic/theme until it’s authentic and personal to them. You could start with a general topic—climate change, for example—and then have each student refine that topic based on their unique background, interests, and curiosity until it’s truly personal and ‘real.’

6. Let students lead. It’s difficult to be curious if the learning is passive and the student doesn’t have any control.

Example: Allow high school students to use our self-directed learning model—or one like it—to create their own project-based learning unit.

7. Spin content. Frame content like a marketer–as new, controversial, ‘frowned upon,’ etc.

Example: Teach a book that’s been ‘banned’ from a book list somewhere.

Be careful with this one—use your best judgment and choose something that’s going to draw interest and possibly agitate, but nothing that will cause problems for students or yourself.)

Being ‘compelling’ is required for many fields and industries, but is often simply ‘encouraged’ in education. While it’s not a ‘teacher’s job’ to entertain students, if you can’t frame what you teach in a way that’s interesting, every day you’re going to be wadding up and throwing away a lot of opportunity for student growth.

8. Focus on questions, not answers.

Example: Questions are an excellent indicator of curiosity. Create a unit-entry lesson and give points for questions—quantity, quality, refinement, etc. The questions are not only evidence and practice of curiosity but can be used as an assessment tool as well. The quality of a question not only reveals curiosity, but background knowledge, literacy level, confidence, student engagement, and more,

9. Connect this to that.

Connect what students don’t know with what they do. This approach can help them activate familiar schema to make sense of new ideas. The more approachable they feel content, projects, or other activities are, the more likely they are to be curious about it.

Example: Compare a historical disagreement between government leaders to a conflict between celebrities on social media, or even ‘beef’ in hip-hop or classic rock and roll.

10. De-school it. Let the content stand on its own.

Example: If there’s a backstory, tell it. For example, on the surface, Arabic numerals (as a topic in and of themselves) don’t seem inherently interesting, but if students understand that as a system it was ‘adopted’ from Hindu scholars by Arab mathematicians and its specific origin is somewhat up for debate, it suddenly becomes more interesting.

In school, we tend to ‘schoolify’ things so that they ‘work’ in a classroom. This often means that whole and full and interesting ‘things’ lose their heads and tails so that we can squeeze them into a timeframe, assessment form, or the like. By returning some content to its more natural ‘state,’ curiosity can be encouraged.