Create An Inquiry-Driven Classroom With These 6 Strategies

contributed by Irena Nayfeld

Teachers of young children juggle a lot.

There are literacy, math, science, social and emotional development, learning standards, the needs of each child, materials to make activities engaging, safe, and educational…the list goes on. More and more, researchers are finding that Habits of Mind and ‘21 Century Skills‘ such as curiosity, persistence, collaboration, growth mindset, critical thinking, and creativity are malleable and, when fostered, improve learning across all academic domains.

Curiosity is a powerful catalyst for learning. Young children want to understand the world around them, and naturally reveal their interests by asking questions – sometimes even too many questions! As educators, we may feel pressure to keep going with our intended lesson plan or to get to our ‘point.’

This may lead us, as teachers, to push ahead instead of listening to a child’s question, or to answer it briefly and move on. The goal of education should be to nurture and grow minds that are ready to solve problems and think critically, and asking questions is a necessary skill in that process.

For this reason, we want to prioritize the asking of great questions and place it at the forefront of our mission for our classrooms and our students.

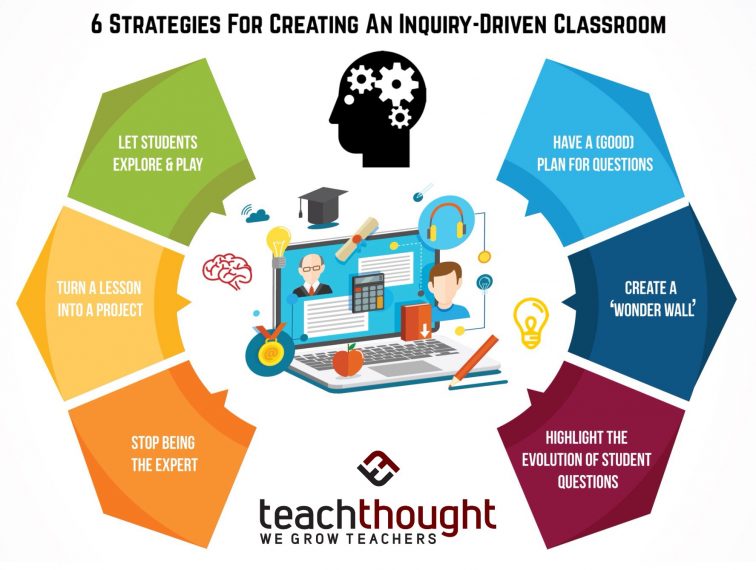

6 Strategies For Creating An Inquiry-Driven Classroom

Given all of the other responsibilities and priorities, how can early childhood educators create environments and experiences that encourage curiosity and inquiry to flourish?

1. Let students explore and learn through play

Imagine you are at a professional development workshop, and the facilitator hands you a bunch of materials for your next project. Before you’ve had the chance to take them in or figure out what’s what, the facilitator says “Okay, what questions do you have?”

Besides “What are these?”, it is hard to come up with in-depth, meaningful questions about the materials or project you have not had any time to explore. Once you have had a chance to examine them closer, touch them, move them, make sense of their relationship to each other, you will likely make observations and start exploring more purposefully; now you are ready to ask some questions and take your understanding of this project to the next level.

Keep this in mind whenever you introduce a new activity to your students- we cannot expect children to ask meaningful questions if they do not have time to explore and play first.

See also 8 Critical Skills For A Modern Education

Spending a whole small group on playing with new materials may seem like ‘wasting time’ but this exploration will pay off – the next day when you are ready to introduce the activity, their desire to touch and play has been fulfilled the day before. This lets them focus on your instructions better and brings in that prior experience as a foundation, which means more engagement, more thoughtful questions, and more lasting learning.

2. Turn a lesson into a project (or project-based learning opportunity)

Often, we feel that every lesson we do has to have a ‘point’ or something concrete that the children created or learned or accomplished. We want to be able to say, ‘Here is what I taught them today. Here is something we can show the parents. Here is a lesson I can check off the list.’

The truth is, real learning takes time, and experiences that gradually build on each other over time can create investment, interest, and understanding that is impossible to create in a one-day lesson.

Creating a whole project might sound intimidating at first. Still, teachers actually find that a project-based mindset takes a lot of pressure off, gives them room to explore children’s interests and use their questions as springboards for exploration while still meeting their requirements and objectives.

Let’s say it’s Halloween and you want to talk about pumpkins. One lesson on pumpkins can become a week-long of science and math activities where children explore the pumpkins first, cut them open and observe the insides, compare them to other fruits and vegetables, measure their size, circumference and weight, and then generate some questions that lead to an ongoing experiment.

What else do we want to know about pumpkins? Maybe one child wants to know what happens if we leave it out – will it rot? How long will it take? Another might wonder how a pumpkin becomes pumpkin pie. A third might ask about where, or how, pumpkins grow.

As the teacher, you can then take that curiosity and pick a question to investigate, teach children how to use find answers using books or technology, and, most importantly, show them that their questions can lead to experiments and explorations and new knowledge!

3. Stop being the expert

Once a question is asked, there are three paths a teacher can take:

1. Ignore the question or tell the student now is not the time.

2. Answer the question as best as you can and keep going with your lesson.

3. Say “I don’t know, but that’s a great question… how can we find out?”

It’s okay not to know the answer! In fact, that can lead to richer, more in-depth and more interesting discussions. When you are not sure of the answer, use it as an opportunity to model curiosity.

Tell the kids you are not sure of the answer and ask for suggestions of how we can find out! They might come up with reading books, watching videos online, using Google, or conducting an experiment to figure out the answer!

Think how much more powerful and lasting this learning will be when the students take ownership, and when the whole class is actively engaged in building the knowledge together!

4. Have a (good) plan for questions

Step 1 is to create a classroom environment where great questions are welcomed. However, if we allow every question to lead to a new discussion or investigation at that moment, we will never finish any lesson we start.

This is why it’s important to have a question action plan or a system in your classroom for how questions are handled. Depending on when the question is asked, answering it or starting a conversation might work just fine.

However, what about questions that are on topic, but would take longer to answer fully? How about questions that would take the lesson too far off course to be addressed at the moment? To empower children and communicate that questions are important, we want to think about where these questions fit in, when they are answered, and by whom.

In an inquiry-driven classroom, questions drive the learning, and students drive the questions.

5. Create a ‘Wonder Wall.’

One way to accomplish this is to help students create a ‘Wonder Wall.’

A Wonder Wall is a great space to “park” questions, but it is only great if children know that there is a set time and procedure for when those questions will be reviewed. Perhaps you pick 1-2 questions to answer during morning circle.

Perhaps you review them yourself during independent work time and then raffle off who gets to find the answer of the computer.

Create a consistent system that works for you and your classroom, and make it a regular part of the routine so that questions are a vehicle for, not a distraction from, learning.

Ed note: Terrell Heick added the item below to add to the author’s ideas.

6. Highlight the evolution of student questions

Similar to the Wonder Wall, consider highlighting not just questions but the evolution of questions–or even publish them somehow to relevant audiences.

How questions change is a strong indicator of understanding. Consider the following scenario:

A student begins a lesson on immigration with a ‘Question Journal Entry,’ What exactly is immigration? After reading an article about immigration they might ask, ‘Do some countries have more immigrants than others? If so, why?’ That’s a great question.

What if they kept building, asking, ‘What problems does immigration cause and solve?

How should governments ‘respond to’ immigration? Should they encourage it? Discourage it?

What sorts of cultural shifts lead to shifts in immigration patterns? For example, how has technology changed immigration? How do policies from world leaders affect immigration?

How should citizens of a nation respond to immigrants? What is the difference between the rights of an immigrant and the rights of a citizen?

How would I feel if I had to immigrate to another country? Does that matter? Who decides? Is that fair that they decide? Does ‘fair’ matter? Who gets to define ‘fair’?

All of these questions indicate higher levels of understanding than the first; questions are outstanding assessment methods.

6 Strategies For Creating An Inquiry-Driven Classroom