A Taxonomy For Transfer: 14 Ways Learners Can Transfer What They Know

by Terrell Heick

What is transfer?

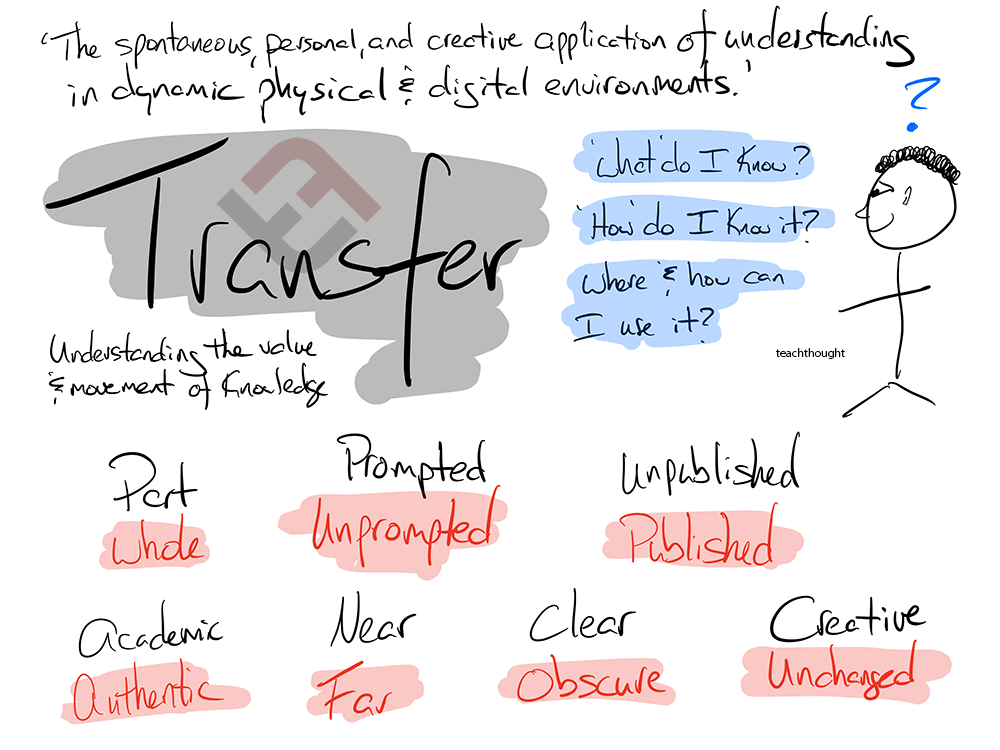

In “Using Self-Transfer To Drive 21st Century Assessment,” I offered that transfer was “the practice of applying knowledge or meaning from a familiar context to an unfamiliar context.”

Further, “This movement requires re-contextualizing what they know, which first requires that they strip ‘what they know’ of all context, consider it in isolation, then adapt it to work elsewhere, a cognitively demanding practice. Of course, this doesn’t happen by admonishing students to “transfer their knowledge,” but rather is the result of transfer-by-design: continuously providing scaffolded learning opportunities for students to prove understanding–and make deeper meaning–by ‘moving’ their understanding…

Transfer is important, but let’s not think just about transfer– let’s think first about the learner, then about their native environments. Then, further, let’s hope for the self-initiated application of knowledge. Unprompted. Unformatted. The spontaneous, personal, and creative application of understanding in dynamic physical and digital environments.”

In “Clarifying Transfer And How It Impacts What We Think Students Understand,” Grant Wiggins went into further detail.

“Students are typically required to make four different cognitive moves to transfer learning successfully: 1) independently realize what the question is asking and think about which answers/approaches make sense here; 2) infer the most relevant prior learning from plausible alternatives; 3) try out an approach, making adjustments as needed given the context or wording; and 4) adapt their answer, perhaps, in the face of a somewhat novel or odd setting (e.g. if the unit of analysis demands rounding or simplifying the result, though this is not needed in these two examples.)

So, ‘content’ can involve merely acquisition goals or both acquisition and transfer goals. It all depends upon our goals for learning that content. And vice versa: just because students are asked to do a complex performance does not mean that any real transfer is demanded. If the task is completely scripted by a teacher – say, memorizing a poem, performing a Chopin Prelude that one has practiced many times, with coaching, or writing a formulaic 5-paragraph essay – then there is no transfer of learning taking place. Transfer only is demanded and elicited when there is some element of novelty in the task and thus strategic thought and judgment is required by the performer.“

Why Is Transfer Important?

Transfer is usually framed in terms of assessment, as it is a kind of marker for understanding. But considered differently, transfer can become a powerful framework to design projects, lessons, units, performance tasks, curriculum maps, self-directed learning projects, and more. It forces the student to consider important questions, including:

What do I know?

How do I know it?

Where and how can I use what I know?

(These kinds of questions are central to the TeachThought Self-Directed Learning Model.)

In short, at the core of transfer is understanding the value of information. We can push this idea further, then, to include the concepts of the adaptation and ‘movement’ of knowledge. Since transfer is, at its essence, about applying knowledge to new and unfamiliar contexts, we can personalize that transfer by seeing it differently–breaking it apart into ‘types’ of transfer. The net result, done well, is a more personalized, authentic, rigorous, and creative learning experience for students.

Below I created 14 categories of cognitive transfer–that is, 14 ways students can transfer their understanding. There are, obviously, hundreds more; if you begin to come up with some on your own, you’ll see what I mean–and maybe understand transfer a bit better yourself.

14 Types Of Transfer Of Learning

Near: Near transfer occurs when there is little ‘distance’ from how the content was learned to where it’s applied (the transfer target)

Example: When a student learns fractions by using blocks as manipulatives and then demonstrates understanding by using LEGOS or pieces of pie or pizza, etc.

Far: Far transfer occurs when there is great ‘distance’ from how the content was learned to where it’s applied

Example: When a student learns fractions by using blocks as manipulatives and then demonstrates understanding by having a conversation about the concepts of fractions or specific strategies in calculating them. Note, this example is also more complex than the setting it was learned within. While the act of ‘transfer’ is inherently more complex than the original learning, ‘Far Transfer’ doesn’t necessarily have to be significantly more complex.

Clear: Clear transfer is when the opportunity for transfer is obvious.

Example: When a student learns fractions by using blocks as manipulatives and then demonstrates understanding by divvying blocks fairly during playtime later that afternoon.

Obscure: The ‘opposite’ to ‘Clear Transfer,’ Obscure transfer is when the opportunity for transfer is not obvious.

Example: When a student learns fractions by using blocks as manipulatives and then demonstrates understanding by using income tax percentage as an example of a kind of ‘fraction.’

Prompted: Prompted transfer occurs when the learner is reminded or required to attempt transfer

Example: When a student learns fractions by using blocks as manipulatives and then demonstrates understanding only when they are asked to do so.

Unprompted: Unprompted transfer occurs when the learner is reminded or required to attempt transfer

Example: When a student learns fractions by using blocks as manipulatives and then demonstrates understanding on their own without being prompted to do so. (This will also almost always be more authentic to the student, too.)

Unpublished: Unpublished transfer is when the act or product of transfer is not made public

Example: When a student learns fractions by using blocks as manipulatives and then demonstrates understanding by showing their parents at home later that evening.

Published: Published transfer is when the act or product of transfer is made public

Example: When a student learns fractions by using blocks as manipulatives and then demonstrates understanding by making a short video to share on FlipGrid or YouTube.

Creative: Creative transfer occurs when the student has or chooses to creatively adapt or alter what’s being transferred

Example: When a student learns fractions by using blocks as manipulatives and then demonstrates understanding by making a stop-motion video or recognizing music half and quarter beats as types of fractions.

Unchanged: Unchanged transfer occurs when the student simply apples what has been learned to a new and unfamiliar situation

Example: When a student learns fractions by using blocks as manipulatives and then demonstrates understanding by cutting a cake evenly in 8 pieces.

Academic: Academic transfer occurs when the transfer is from one academic context to another

Example: When a student learns to calculate percentages using a calculator during a quiz and then demonstrates understanding by the same thing on a test or during a learning station task in the classroom.

Authentic: Authentic transfer is when the transfer is from an academic to an authentic context

Example: When a student learns about symbolism by learning about government logos and then demonstrates understanding by creating their own logo for a project they are working on.

Part: Part transfer occurs when only a portion of what was learned is transferred

Example: When a student learns fractions by using blocks as manipulatives and then demonstrates understanding by counting blocks or making separate piles of blocks that may or may not be evenly distributed.

Whole: Whole transfer occurs when the content transferred is done so in whole

Example: When a student learns fractions by using blocks as manipulatives and then demonstrates understanding by using all of the skills or concepts learned previously in a new and unfamiliar situation.

Categories Of Cognitive Transfer: 14 Ways Students Can Transfer What They Know