Cognitive Load Theory: A Definition

by Terry Heick

Preface: I’m (very clearly) not a neurologist. While I often have dedicated a lot of thought and research into things I write, sometimes I write about things in order to understand them–or understand them better. This is one of those times.

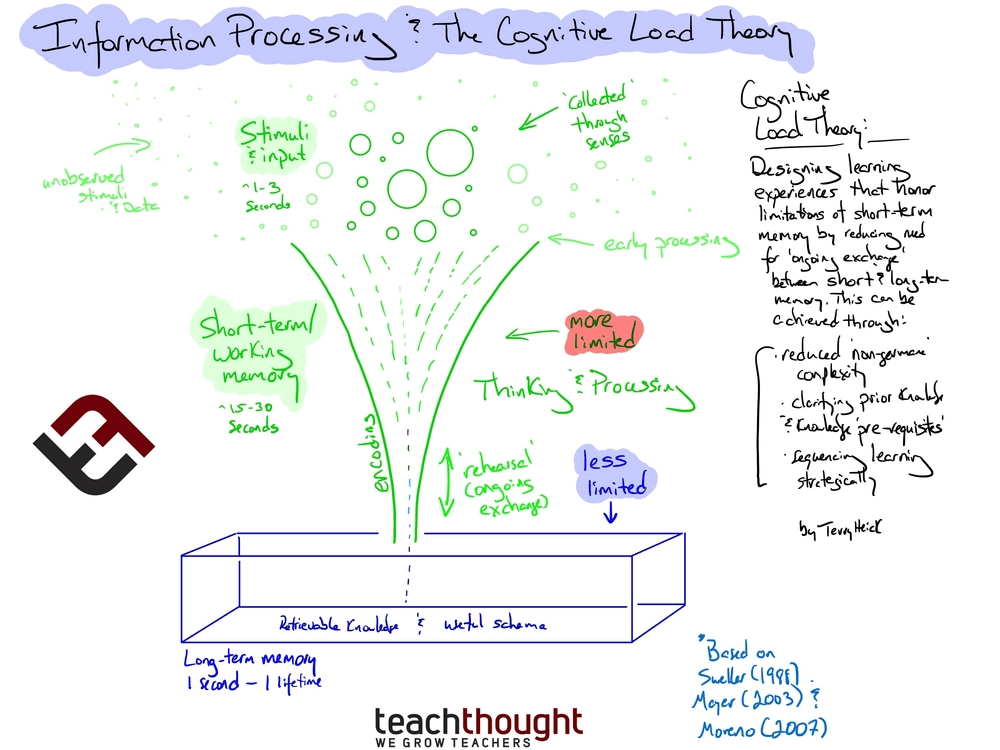

Generally, the Cognitive Load Theory is a theory about learning built on the premise that since the brain can only do so many things at once, we should be intentional about what we ask it to do.

It was developed in 1998 by psychologist John Sweller, and the School of Education at New South Wales University released a paper in August of 2017 that delved into theory. (I’ve linked to the study three times and the URL has been moved three times so you’ll have to search to find it if you want to access it directly.) The paper has a great overview–and even stronger list of citations–of the theory. They also, obviously, define and explain it:

‘Cognitive load theory is based on a number of widely accepted theories about how human brains process and store information (Gerjets, Scheiter & Cierniak 2009, p. 44). These assumptions include: that human memory can be divided into working memory and long-term memory; that information is stored in the long-term memory in the form of schemas; and that processing new information results in ‘cognitive load’ on working memory which can affect learning outcomes (Anderson 1977; Atkinson & Shiffrin 1968; Baddeley 1983).’

Put another way, the Cognitive Load Theory says that because short-term memory is limited, learning experiences should be designed to reduce working memory ‘load’ in order to promote schema acquisition.

Since both can’t be done well at the same time, teachers can be specific about not just what is being learned (e.g., content knowledge versus procedural knowledge) and the sequence of the learning (e.g., learn about a ‘thing,’ then how that ‘thing’ works, then how to use that ‘thing’ critically and creatively) it is, but also the nature of what’s being learned (e.g., domain-specific knowledge and definitions versus design thinking through knowledge and definitions).

For example, if you asked a student to critically examine various economic systems (higher-order thinking) while also defining and ‘making sense of’ what an ‘economic system’ was and how they worked, you’d be overloading short-term memory. Because the student doesn’t yet ‘understand’ economic systems, they would need to consistently access their short-term memory while processing–while ‘learning.’ The concept of ‘economic systems’ is not yet in their long-term memory, so as they ‘create knowledge’ (moving new ‘information’ into existing or emerging schema), their short-term memory becomes cluttered because it is the primary ‘ground zero’ for the learning.

The student could likely still learn under these circumstances, but the instructional design in this scenario is non-optimal–the student would literally be fighting the way their brain works in order to learn.

Or so says the Cognitive Load Theory anyway.

Of course, a teacher doesn’t want students fighting an uphill battle just to acquire new knowledge. We want students to grapple with complexity, but that’s very different than defying neurology and making things unnecessarily complicated. This creates a poor feedback loop for learning for the student.

Another (Slightly Longer) Definition For Cognitive Load Theory

Wikipedia has one of the best (though slightly longer) definitions for the Cognitive Load Theory I’ve seen.

‘Cognitive load theory provides a general framework and has broad implications for instructional design, by allowing instructional designers to control the conditions of learning within an environment or, more generally, within most instructional materials. Specifically, it provides…guidelines that help instructional designers decrease extraneous cognitive load during learning and…refocus the learner’s attention toward germane materials, thereby increasing germane (schema-related) cognitive load.’

The Theory In Sweller’s Own Words: A Psychologist’s Definition

In 1988, Sweller himself wrote that:

‘Cognitive load theory has been designed to provide guidelines intended to assist in the presentation of information in a manner that encourages learner activities that optimize intellectual performance. The theory assumes a limited capacity working memory that includes partially independent subcomponents to deal with auditory/verbal material and visual/2- or 3-dimensional information as well as an effectively unlimited long-term memory, holding schemas that vary in their degree of automation. These structures and functions of human cognitive architecture have been used to design a variety of novel instructional procedures based on the assumption that working memory load should be reduced and schema construction encouraged.”

See also Is The Cognitive Load Theory The Most Important Thing Every Teacher Should Know?

Ultimately, the Cognitive Load Theory also suggests that ‘knowing things’ is necessary to think critically about those things–or at least is most efficient when that is the case.

This further suggests that two of the primary information processing ‘activities’ here (knowledge acquisition and problem-solving) should be considered separately, oftentimes focusing first on schema, then on problem-solving with and through that schema.

Sweller continues, “It is suggested that a major reason for the ineffectiveness of problem-solving as a learning device, is that the cognitive processes required by the two activities overlap insufficiently, and that conventional problem-solving in the form of means-ends analysis requires a relatively large amount of cognitive processing capacity which is consequently unavailable for schema acquisition.”

Put another way, the reason problem-solving and domain knowledge aren’t directly proportional is because of how the human brain works. Problem-solving takes up crucial ‘brain bandwidth,’ reducing what’s ‘left’ to ‘learn new things.’

Of course, this has significant implications for how teachers might design lessons, units, and assessments, and for how curriculum developers use instructional design elements that brain-based learning.

A Few Thoughts About The Theory

The paper from NSW offers a slightly confusing ‘cognitive load-friendly’ strategy:

‘Cognitive load theory supports explicit models of instruction, because such models tend to accord with how human brains learn most effectively (Kirschner, Sweller & Clark 2006). Explicit instruction involves teachers clearly showing students what to do and how to do it, rather than having students discover or construct information for themselves (see Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation 2014, pp. 8-12).

I’m honestly not sure what to take away from this bit–maybe that the nature of explicit instruction is ‘Cognitive Load Theory’-friendly because students are less frequently overloading short-term memory…maybe because the teacher is reducing ‘load’ by modeling and explaining and being extremely clear and explicit? In which case, the brain is free to ‘learn’ the specified learning objective?

That sounds great, but by being so narrow and ‘clear,’ it leaves very little room for personalization unless the teacher:

1. Was crystal clear–from the academic standard to the curriculum map to the unit to the lesson objective–what was was being learned and the cognitive level it was being learned at. For example, any academic standard that require the student to evaluate the bias in an author’s position, for example, would itself need to be parsed to separate

2. Had fresh and accurate assessment date evaluating the prior knowledge each student came to that lesson with

3. Designed some way to accommodate a wide variety of existing understandings so that the ‘load’ was reduced per student rather than per standard or content topic

And there’s zero chance of that happening consistently–which suggests education be looked at with fresh and honest eyes of how the brain works, and everything else–from curriculum to classrooms–be designed in response.

Conclusion

Anyhow, there you are. A definition for and brief discussion of the Cognitive Load Theory.

There are scores and scores of ‘theories’ worth looking at, but this one stood out to me because it doesn’t mean exactly what it sounds like it means, and in a neat and tidy way, kind of frames how all teaching and learning most naturally happen: in small movements, building in small increments of progress until something close to mastery emerges and learners can see what the value of the ‘learned thing’ is, and what the true utility of that knowledge might be.

What Is The Cognitive Load Theory? A Definition For Teachers