How Learning Is Different Than Education

by Terry Heick

Ed note: This post has been updated from an early 2013 post.

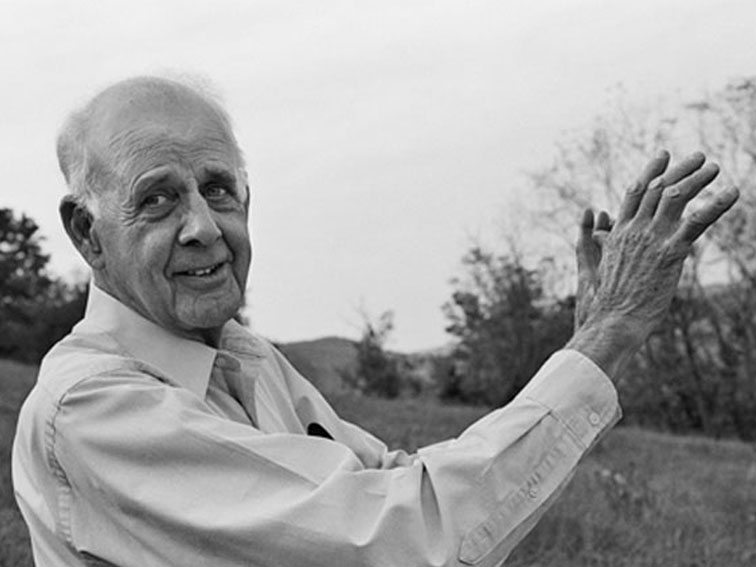

“…all our problems tend to gather under two questions about knowledge: Having the ability and desire to know, how and what should we learn? And, having learned, how and for what should we use what we know?”

Wendell Berry, likely America’s greatest living writer and certainly its most compelling essayist, succinctly captures the challenge of education in this excerpt on an essay from a (mostly) unrelated topic from “People, Land, and Community.”

But in the quote, Berry (whose ideas we’ve used to reflect on learning before, including this Inside-Out School Learning Model) has given us the ingredients for an authentic system of learning.

The challenge of the ability and the desire to know is well enough established. While education as a system has (for the most part) moved long past concepts of “intelligence” and ability on the surface, academic progress and proficiency are literal linchpins for all education reform, at least in the United States. Establish a curriculum, agree on how to measure the learning progress of that curriculum, and then promise to stakeholders that all students will meet that level and “not be left behind.”

The How and What of learning—which immediately brings to mind instructional strategies and curriculum matters—are really much more complicated. This complexity—of how to parse the world and “cause literacy”—and literacy of what—has been homogenized in the United States with the adoption of Common Core academic standards, so that all students will study the same material, in much the same ways and with the same remediation patterns as suggested by the same assessment forms.

The last bit of his thought is a bit more troubling. “Having learned, how and for what should we use what we know?”

To educators, this likely sounds like “career readiness,” but just as learning is much different than education, the “work” a person does in interacting with the world is much different than a “career.”

Learning:Education::Work:Career.

The use of project-based learning and place-based education to help students address authentic personal and social problems is becoming more common—or at least more visible.

But helping students understand how to meaningfully interact with the communities and networks and issues and tools that are most important to them often means we have to bring them to communities and networks and issues and tools both familiar and unfamiliar, and to re-contextualize issues they think they understand.

This kind of intellectual agitation cannot possibly be purely academic, as academics do not exist outside of classrooms.

A push for “career readiness” makes sense in light of decaying workforce skills in a world that increasingly demands more. But a school can no more teach a child to have a conscience than they can train their minds for the work of their life.

This suggests the need for deep and persistent and meaningful and equitable interaction between schools and the communities they serve. For the communities to have the capacity to truly support 21st-century learning, they need to be a part of the process from the beginning, not detached receivers of lukewarm project-based learning artifacts.

Schools can no longer martyr on promising miracles while spending billions and working teachers into the ground.

Learning is different than education. One can be self-directed but supported; the other is led and caused. One is driven by curiosity and the joy of discovery; the other is metered and measured, and a matter of endless policy and mechanization.

Education and all of its bits and pieces–with some modesty and connectivity–can become the ultimate learning tool in any community. Teachers can be the champions of the gift of learning and the power of well-wrought education, but only if they can find mirrors of themselves in communities–symmetrical in both form and function.

21st-century learning must be, if nothing else, interdependent and communal, and sensitive to these distinctions.