What Is The Difference Between ‘Learning Styles’ & ‘Multimodal Learning’?

The learning styles debate has been going on for some time.

We saw the concept of learning styles experience significant popularity in the late 20th century. Many teachers have likely seen or distributed a learning styles inventory as a first-day-of-school activity. In the last several years, many have asserted that learning styles are actually a myth.

We have written about learning styles before–and we’re not ready to abandon the concept just yet. That being said, we do believe that the term ‘learning styles’ is often misunderstood, misused, and misrepresented. In this post, we’re setting out to separate myth from reality (based on research).

What Is The Learning Styles Theory & Where Did It Originate?

According to the learning styles theory, a self-reported visual learner learns best through interacting with visual content, a self-reported auditory learner learns best through hearing content, a self-reported reader/writer learner learns best when they read or write content, and a kinesthetic learner learns best by physically manipulating new content or moving in some way.

‘Learning styles’ were recognized as early as 334 BC by Aristotle, who espoused that “each child possessed specific talents and skills” (Reiff & NEA,1992). Future researchers have since come up with their own theories about learning. For example, Lev Vygotsky believed that learning is social, and Jean Piaget believed that cognitive development is a precursor for learning. Howard Gardner’s multiple intelligences theory proposes that students can be categorized as a composite of distinct learning styles (visual-spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, interpersonal, intrapersonal, linguistic, and logical-mathematical). Neil Fleming developed the VARK questionnaire – which stands for ‘visual, aural, read/write, and kinesthetic’ to determine someone’s ‘learning style’–the preference of students in how they absorb and share information.

It is here, perhaps, where the concept of learning styles started to take on mythical proportions.

How Did The Idea Of Learning Styles Gain Popularity?

Perhaps the naturally appealing notion of being able to understand one’s own brain processes with just a few questions on the VARK questionnaire is why learning styles morphed into a misunderstanding. Some believe that the ‘Everyone is Special’ self-esteem movement of the 80s and 90s is responsible.

The current conception of learning styles is not so much mythical as it is an incomplete perspective that persists in modern education. A 2017 study conducted by researchers at the University of Houston and the University of Denver recruited over 3,800 people (including 598 teachers) to take a survey on brain myths. The researchers found that 93% of the public, 76% of teachers, and 78% with neuroscience education endorsed the idea that each person has one primary mode of learning.

Education leaders are unsure why the incomplete perspective of learning styles remains popular. Some wonder if teacher education programs are promoting the idea. In a literature review of scholarly research on learning styles, 94% of the research papers include a positive view of learning styles (in its limited conception), and 89% endorse its use in higher ed. Others propose that teachers may be repeating the strategies their own teachers deployed in their personal K-12 experience.

What Are Educators And Education Leaders Missing When It Comes To Learning Styles?

So what’s the problem? Does every person out there in the world have a different learning style? Yes. Is it important for teachers to know how their students learn best in order to plan for instruction? Yes. Should teachers prompt students to think about how they learn best as a way to approach a task? Yes.

HOWEVER…

Can the complexity of how the brain learns be so simply boiled down as to one of three distinct modalities? No. Should teachers label students as strictly visual learners, auditory learners, or kinesthetic learners? No. Should teachers design your entire curriculum and tailor instruction according to results from a basic learning styles inventory? No.

There are two immediately obvious problems with the popular conception of learning styles.

First, recent neurobiology research suggests that, as we learn, our brains are constantly wiring and rewiring connections–this phenomenon of the brain is called neuroplasticity. Our software is constantly updating, which means that how we learn is also constantly evolving. More accurately, we use a combination of auditory, kinesthetic, visual, and reading/writing faculties to learn, depending on the purpose, our motivation, and audience. We may learn differently depending on the level of complexity our brains are being tasked with navigating.

Second, if we could label and categorize students based on their learning styles, that assumes that a student’s effort and ability are not connected to their success; rather, the teacher’s ability to identify and cater to their learning style is paramount. Learning just isn’t that simple.

Learning Styles And Multimodal Learning, Not Versus

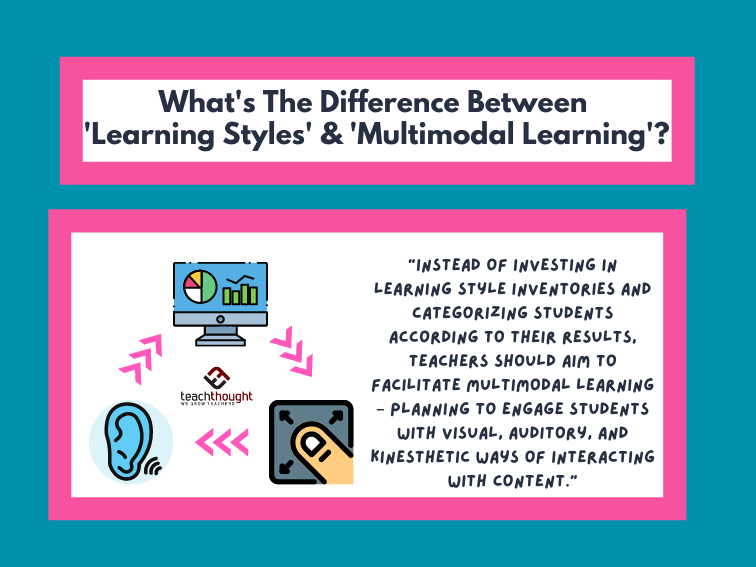

Instead of investing in learning style inventories or categorizing students according to their self-reported learning styles, teachers should really be aiming to facilitate multimodal learning – planning to engage students with visual, auditory, and kinesthetic ways of interacting with content. That’s what the original conception of learning styles was all about.

Let’s set up an analogy. Imagine that you’re making pasta bolognese. If the elements of the sauce symbolize the ways in which we learn, then we know that not everyone’s pasta is going to taste the same! In some iterations, the ground beef, pork, or veal are the prominent elements. Other chefs may rely more on the onions, celery, carrots, and mushrooms. Others, still, may want the tomato sauce to outshine the other elements. It comes down to a matter of preference and wiring, but without all of the ingredients I just listed, there’s not going to be a delicious bolognese.

Research clearly indicates that significant improvements in learning can be reached through the effective use of multimodal learning. We know the following to be accurate:

- Learners retain more through words and pictures versus through words alone

- Learners retain more when words and pictures are close in proximity

- Learners retain more when words and pictures are presented simultaneously

- Learners retain more when extraneous words, pictures, and sounds are omitted

- Learners retain more from animation and narration versus animation and on-screen words

- Learners retain more when redundancy is avoided

When planning for curriculum and instruction, look inside your teacher toolbox and consider:

- Which tools, activities, and interactions are best suited for helping students retain new content?

- How do my current multimedia materials aid or hamper the learning process?

- How can I get my students to think about their own learning?

The mutation of the concept of learning styles challenges teachers with being all things for all learners, which isn’t what students need. The best way to foster learning in your classroom is to give students multiple avenues to interact with new content in meaningful ways through multimodal learning.

References

Reiff, J. C. (1992). Learning styles. What research says to the teacher, 7. Washington, DC: National Education Association.