What Are The Most Common Misconceptions About Bloom’s Taxonomy?

by Grant Wiggins & The TeachThought Staff

Admit it–you only read the list of the six levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy, not the whole book that explains each level and the rationale behind the Taxonomy. Not to worry, you are not alone: this is true for most educators.

But that efficiency comes with a price. Many educators have a mistaken view of the Taxonomy and the levels in it, as the following errors suggest. And arguably the greatest weakness of the Common Core Standards is to avoid being extra-careful in their use of cognitive-focused verbs, along the lines of the rationale for the Taxonomy.

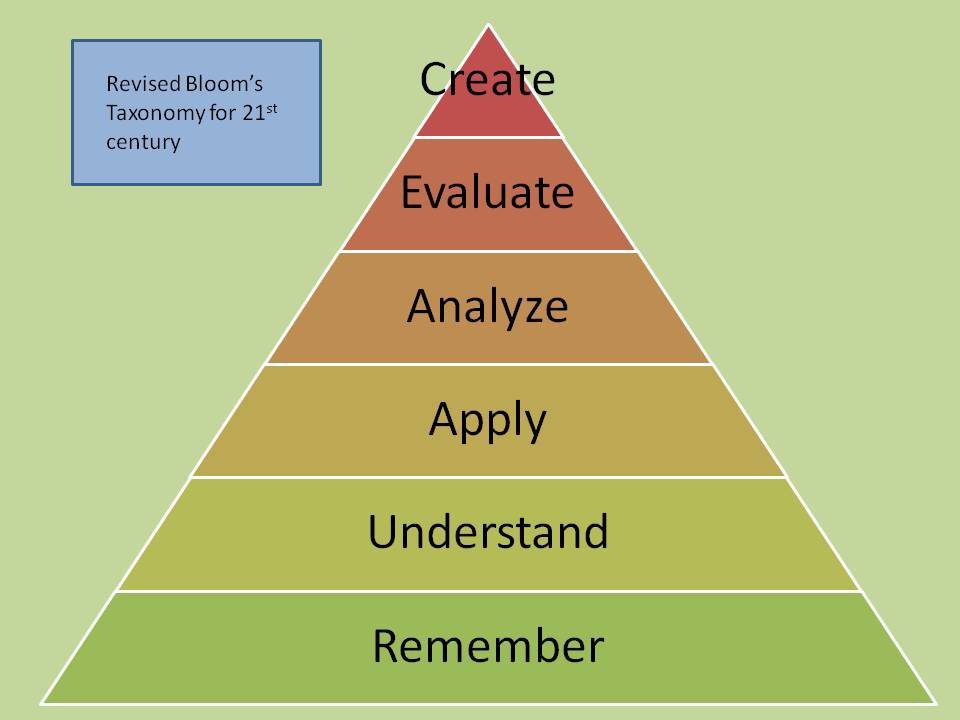

1. The first two or three levels of the Taxonomy involve ‘lower-order’ and the last three or four levels involve ‘higher-order’ thinking.

This is false. The only lower-order goal is ‘Knowledge’ since it uniquely requires mere recall in testing. Furthermore, it makes no sense to think that ‘Comprehension’ – the 2nd level – requires only lower-order thought:

The essential behavior in interpretation is that when given a communication the student can identify and comprehend the major ideas which are included in it as well as understand their interrelationships. This requires a nice sense of judgment and caution in reading into the document one’s own ideas and interpretations. It also requires some ability to go beyond mere rephrasing of parts of the document to determine the larger and more general ideas in it. The interpreter must also recognize the limits within which interpretations can be drawn.

Not only is this higher-order thinking – summary, main idea, conditional and cautious reasoning, etc.–it is a level not reached by half of our students in reading. And by the way: the phrases ‘lower-order’ and ‘higher-order’ appear nowhere in the Taxonomy.

2. “Application” requires hands-on learning.

This is not true, a misreading of the word “apply”, as the text makes clear. We apply ideas to situations, e.g. you may comprehend Newton’s 3 Laws or the Writing Process but can you solve novel problems related to it – without prompting? That’s application:

The whole cognitive domain of the taxonomy is arranged in a hierarchy, that is, each classification within it demands the skills and abilities which are lower in the classification order. The Application category follows this rule in that to apply something requires “comprehension” of the method, theory, principle or abstraction applied. Teachers frequently say, “If a student really comprehends something then he can apply it.”

A problem in the comprehension category requires the student to know an abstraction well enough that he can correctly demonstrate its use when specifically asked to do so. “Application,” however, requires a step beyond this. Given a problem new to the student, he will apply the appropriate abstraction without having to be prompted as to which abstraction is correct or without having to be shown how to do it in this situation.

Note the key phrases: Given a problem new to the student, he will apply the appropriate abstraction without having to be prompted. Thus, “application” is really a synonym for “transfer”.

In fact, the authors strongly assert the primacy of application/transfer of learning:

The fact that most of what we learn is intended for application to problem situations in real life is indicative of the importance of application objectives in the general curriculum. The effectiveness of a large part of the school program is therefore dependent upon how well the students carry over into situations applications which the students never faced in the learning process. Those of you familiar with educational psychology will recognize this as the age-old problem of transfer of training. Research studies have shown that comprehending an abstraction does not certify that the individual will be able to apply it correctly. Students apparently also need practice in restructuring and classifying situations so that the correct abstraction applies.

Why UbD is what it is. In Application problems must be new; students must judge which prior learning applies, without prompting or hints from scaffolded worksheets; and students must get training and have practice in how to handle non-routine problems. We designed UbD, in part, backward from Bloom’s definition of Application.

As for instruction in support of the aim of transfer (and different types of transfer), the authors soberingly note this:

“We have also attempted to organize some of the literature on growth, retention, and transfer of the different types of educational outcomes or behaviors. Here we find very little relevant research. … Many claims have been made for different educational procedures…but seldom have these been buttressed by research findings.”

3. All the verbs listed under each level of the Taxonomy are more or less equal; they are synonyms for the level.

No, there are distinct sub-levels of the Taxonomy, in which the cognitive difficulty of each sub-level increases.

For example, under Knowledge, the lowest-level form is Knowledge of Terminology, where a more demanding form of recall is Knowledge of the Major Ideas, Schemes and Patterns in a field of study, and where the highest level of Knowledge is Knowledge of Theories and Structures (for example, knowing the structure and organization of Congress.)

Under Comprehension, the three sub-levels in order of difficulty are Translation, Interpretation, and Extrapolation. Main Idea in literacy, for example, falls under Interpretation since it demands more than “translating” the text into one’s own words, as noted above.

4. The Taxonomy recommends against the goal of “understanding” in education.

Only in the sense of the term “understand” being too broad. Rather, the Taxonomy helps us to more clearly delineate the different levels of understanding we seek:

To return to the illustration of the term “understanding” a teacher might use the Taxonomy to decide which of several meanings he intended. If it meant that the student was…aware of a situation…to describe it in terms slightly different from those originally used in describing it, this would correspond to the taxonomy category of “translation” [which is a sub-level under Comprehension]. Deeper understanding would be reflected in the next-higher level of the Taxonomy, “interpretation,” where the student would be expected to summarize and explain… And there are other levels of the Taxonomy which the teacher could use to indicate still deeper “understanding.”

5. The writers of the Taxonomy were confident that the Taxonomy was a valid and complete Taxonomy

No they weren’t. They note that:

“Our attempt to arrange educational behaviors from simple to complex was based on the idea that a particular simple behavior may become integrated with other equally simple behaviors to form a more complex behavior… Our evidence on this is not entirely satisfactory, but there is an unmistakable trend pointing toward a hierarchy of behaviors.

They were concerned especially that no single theory of learning and achievement–

“accounted for the varieties of behaviors represented in the educational objectives we attempted to classify. We were reluctantly forced to agree with Hilgard that each theory of learning accounts for some phenomena very well but is less adequate in accounting for others. What is needed is a larger synthetic theory of learning than at present seems available.

Later schemas – such as Webb’s Depth of Knowledge and the revised Taxonomy – do nothing to solve this basic problem, with implications for all modern Standards documents.

Why This All Matters

The greatest failure of the Common Core Standards is arguably to have overlooked these issues by being arbitrary/careless in the use of verbs in the Standards.

There appears to have been no attempt to be precise and consistent in the use of the verbs in the Standards, thus making it almost impossible for users to understand the level of rigor prescribed by the standard, hence levels of rigor required in local assessments. (Nothing is said in any documents about how deliberate those verb choices were, but I know from prior experience in New Jersey and Delaware that verbs are used haphazardly – in fact, writing teams start to vary the verbs just to avoid repetition!)

The problem is already on view: in many schools, the assessments are less rigorous than the Standards and practice tests clearly demand. No wonder the scores are low. I’ll have more to say on this problem in a later post, but my prior posts on Standards provide further background on the problem we face.

Update: Already people are arguing with me on Twitter as if I agree with everything said here. I nowhere say here that Bloom was right about the Taxonomy. (His doubts about his own work suggest my real views, don’t they?) I am merely reporting what he said and what is commonly misunderstood. In fact, I am re-reading Bloom as part of a critique of the Taxonomy in support of the revised 3rd edition of UbD in which we call for a more sophisticated view of the idea of depth and rigor in learning and assessment than currently exists.

This article first appeared on Grant’s personal blog; Grant can be found on twitter here; 5 Common Misconceptions About Bloom’s Taxonomy; image attribution flickr user langwitches