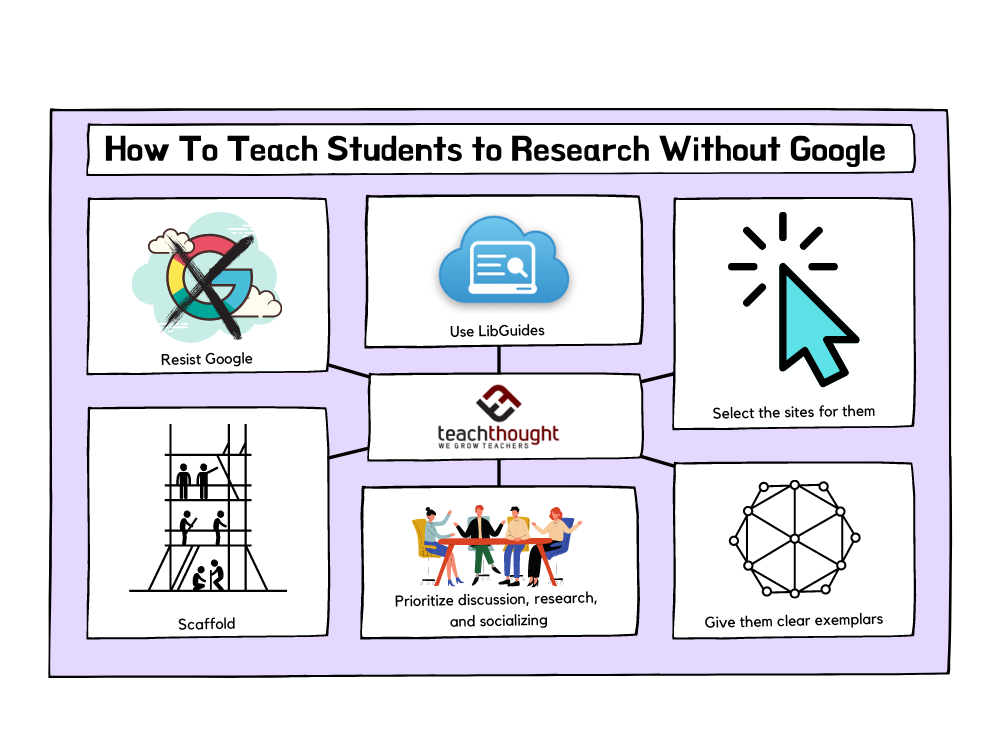

Teaching Students To Research Without Using Google

contributed by Jane Healey, Ph.D

Inquiry-based learning is one of the current buzz phrases, meaning students should ask and answer questions as a primary method in the classroom. It’s a great initiative, but it puts teachers on the hot seat.

Most people teaching today weren’t trained to instruct students about researching in a technologically advanced world. Many need a quick refresher course or tutoring packet on successful student research. The tips below are meant to help teachers and students get off to a good start as they embark on an inquiry adventure.

1. Resist Google

Most adults in a school environment can easily use Google to search for information. We understand the search engine’s purpose, we know it’s a commercial entity, and we can quickly scan a list, culling for the most credible and relevant sites. We even have patience to look at a second or third page of results.

Students don’t know how the search engine works or makes money, and they usually can’t judge a site’s credibility even while using it. My favorite example was a site that ‘looked good’ according to the students, but when I hit the ‘Who We Are’ tab, a cat laying on a computer keypad greeted us.

Google isn’t ‘bad’; everyone, including students uses it for general information answers. But more serious questions like those of research need more precise methods to find answers. (See our post on How Technology Impacts Curiosity.)

2. LibGuides

Many schools use LibGuides to keep students off popular search engines and focused on a specific range of useful resources. These lists provide students with previewed credible sites to search for materials on a topic.

Teachers customize the lists of sites for a specific class, tailoring the available resources to suit the research topics. In this manner, students become familiar with appropriate ‘go-to’ sites, learning how to recognize ‘good’ sites. The hope is that when another opportunity to search arises, students will seek the helpful, credible ones they know instead of the ‘easy’ search engines they really don’t know.

3. Select The Sites For Them

If a LibGuide isn’t available, teachers create a customized list for students or upload links on the class website. In my US History course, I upload a guide that includes the National Archives, the Library of Congress, the National Park System, Smithsonian Magazine as well as the museums and more. By the end of the year, no one would consider using a source beyond the lengthy list of good ones.

Every subject has a similar cache of reputable places to look for information. Medicine? The CDC and National Institute of Health. Art? The National Gallery, The Met, MOMA. Some teachers’ LibGuides are available online, and they provide great ideas. In addition, brainstorming with colleagues helps develop a full list.

4. Give Them Clear, Exemplar Models

Students tend to stop looking for articles after they locate secondary sources like encyclopedias. Diving into more diverse sources seems difficult for them and beyond the realm of their notions of ‘research.’ I lean on the method of document based questions from history courses. I gather a wide collection of ‘documents,’ and during class, students practice analyzing materials and answering questions.

An English teacher reading Catcher in the Rye might ask students to respond to questions about the experience of boarding school. Groups get a packet that includes photos, attendance profiles, prose descriptions, biographies of headmasters, layouts of campuses, and other documents. After digging into two or three of these packets, students value the significance of visual documentation, first-person narratives, maps, and other information well beyond encyclopedias.

As I’ll propose below, during these reviews of a variety of sources, the students talk to each other while they read, review and analyze. They like to note an odd fact, ask if others knew a strange story, and shout surprise at huge numbers. When the time comes for them to find patterns or themes, they discuss the materials again, supporting their comments by referencing a document. The conversation raises the learning curve for all the students.

5. Discussion–>Research–>Socializing

Researchers don’t hide in archives for months at a time emerging with finalized reports. They share work with colleagues who help shape the project with their reactions. Discussing projects at intermediary stages offers students a chance to get feedback before they commit to a culminating report.

To mimic the ritual of reading groups, teachers ask students to verbally provide a daily update that offers teachers a way to check on their progress and allows peers to offer help. Often, one student shares a source with another, and soon they are asking each other for ideas. This method also elicits more questions than asking, “Are there any questions?”, because everyone is asking someone something.

6. Scaffold!

Before assigning the Big One, students often need mini-projects that slowly introduce categories of resources one at a time. For example, a course might start with an assignment to write a biographical sketch that requires an encyclopedia and a dictionary of famous people. Now they’ve covered general reference items.

Next, a cultural review assignment might require the same two or similar general reference materials plus two pieces from a newspaper, a magazine, online media outlet or other mass reference source. (PBS, NPR and the major news organizations are great for this step.)

With this foundation in basic knowledge searching, the students can tackle a project requiring a point of view or argument and finding at least 6-8 sources, including at least one university offering. The students have practiced the elementary stages of research and can now spend their intellectual energy struggling with locating and reading university-level materials and crafting a strong culminating event.

Students find research overwhelming so slowing the process down and isolating one skill at a time or one resource at a time builds their confidence, the quality of their larger projects, and the teacher’s pleasure with the process.

“Resist Googling” & 5 Other Strategies For Meaningful Modern Research; How To Teach Students To Research Without Google