What Does “College Ready” Really Mean, Anyway?

What Does “College Ready” Really Mean, Anyway?

by Terry Heick

Yesterday, I was talking to my 14 year old daughter yesterday about the kinds of skills that translate to academic success.

I also actually used the sterile phrase “academic success.” This was an important distinction, as she’s home-schooled (another term I dislike) and learns through a kind of hybrid approach–a self-directed learning framework coupled with inquiry, combined with traditional academic tools. So for her, learning can happen on her phone, outside painting, writing her own music, or within the boundaries of a scripted lesson or unit.

And while that’s true for anyone, her learning, on a day-to-day basis, is designed that way. So when she talks about what it means to “do well in school,” she has to shift her thinking. As teachers, we often think of our classrooms and schools as “learning,” but really it’s only one form of learning with very strong flavors and tone–one driven by the idea of coverage over mastery, with that mastery measured by mostly universal assessments, and with the motivation to learn mostly institutional–letter grades, certification, endorsements, titles, etc.

You can fail.

“Drop out.”

Get “kicked out.”

Be interviewed.

Be selected.

Be rejected.

This approach has alienated a significant number of potentially brilliant children who, for whatever reason, didn’t make the cut, which creates a useful context to rethink education. Right, so, with Madison (my daughter), I told her that the universal skills of “doing well in school” (college, in this case) were literacy (close reading, skimming, note-taking, argument analysis and formation, the writing process, etc.), research (inquiry, sources, citations, and–the big one–understanding the value of specific data, and how to package that in an argument of your own), resourcefulness (to know where to go for what, and when), and communication (working together with peers, teachers, and other university–and external–resources, getting help, etc.).

Of course, this is incomplete. I was standing over her on the deck while she read, not giving a formal presentation. Still, I was trying to make the case to her how you learn is more important than what you know.

What Does “College-Ready” Mean?

This begs the question, What should high school prepare students for? A job? College? These limited answers, to me, miss the point of education entirely, but I’ll get to that in another post. In K-12 we tend to focus on grades and content knowledge, success in college, and then within any “careers,” may have unique factors. Grit is often the face of these skills, to which we can add resourcefulness, communication, collaboration, time-management, and other famously “soft skills.” The first two years of an undergrad degree can be much different than the next two (or three). Before being concerned with a major, there are General Education Requirements to fulfill, which dictate that a student have specific skills in math or reading or language, and that strong or poor performance on ACT/SAT testing can increase or reduce this work. So to suggest that content knowledge doesn’t matter would be incorrect. It’s possible, though, that the hardest academic work might depend most on the softest of skills.

A student might be thought of as “prepared for college” when they are highly literate, research fluent, self-motivated, and eager to connect with the people and ideas and resources and opportunities around them. But that’s too broad for policy, apparently. Or too narrow. In an article on Politico, David T. Conley, a University of Oregon education professor who has researched both Common Core and college readiness, explains, “It’s not just that people don’t agree on what ‘ready’ means. It’s that most of the definitions of ‘ready’ are far too narrow, and we don’t gather data in many key areas where students could improve their readiness if they knew they needed to do so.”

Not sure this makes sense, though. We need precise definitions and indicators for each specific student and their apparent “college readiness”? Like high school readiness? Or middle? Or the most problematic–career readiness? All of the “key areas” parsed and visible for teachers to “plan learning experiences”?

The more ambitious the scale of our improvement, the more we lose sight of the student in front of us–the one seeking wisdom, or the science background that nurtures a love of medicine, or the creative expression to become an artist, or the sheer courage to farm. College is just a word. The reasons for going to college is a more specific group of words, but also misunderstood (see the college dropout rate, which is somehow attributed to lack of “prep” instead of the high cost or dubious utility of many college classes). This whole education-to-life connection is a bit murky.

College Isn’t For Everybody

Without something at least approaching the universe of this kind of thinking, college is often a matter of momentum and social expectation and rat race. And 18 is way, way too early to enter the rat race. As a culture, we have an odd infatuation with college instead of the currency and output and rhythms of knowledge and people. College-worship is a deadly practice–same with GPA worship and letters-after-your-name ego. It’s nutty. The truth is, you never really know if a student is ready for college, because the college may not be ready for that student and their needs and dreams and vision.

College isn’t for everybody. If we were all rich and privileged, we could send every student to a 4-year undergrad program that could help give them a broad foundation of somewhat-personalized learning that high school never could. But some teens have babies. Or anxiety. Or creative angst. Or a need to provide for their family. Or learning disabilities. Or no sense of themselves as writers or thinkers. Or ambition bigger than a university campus.

This can’t all be untangled in middle and high school.

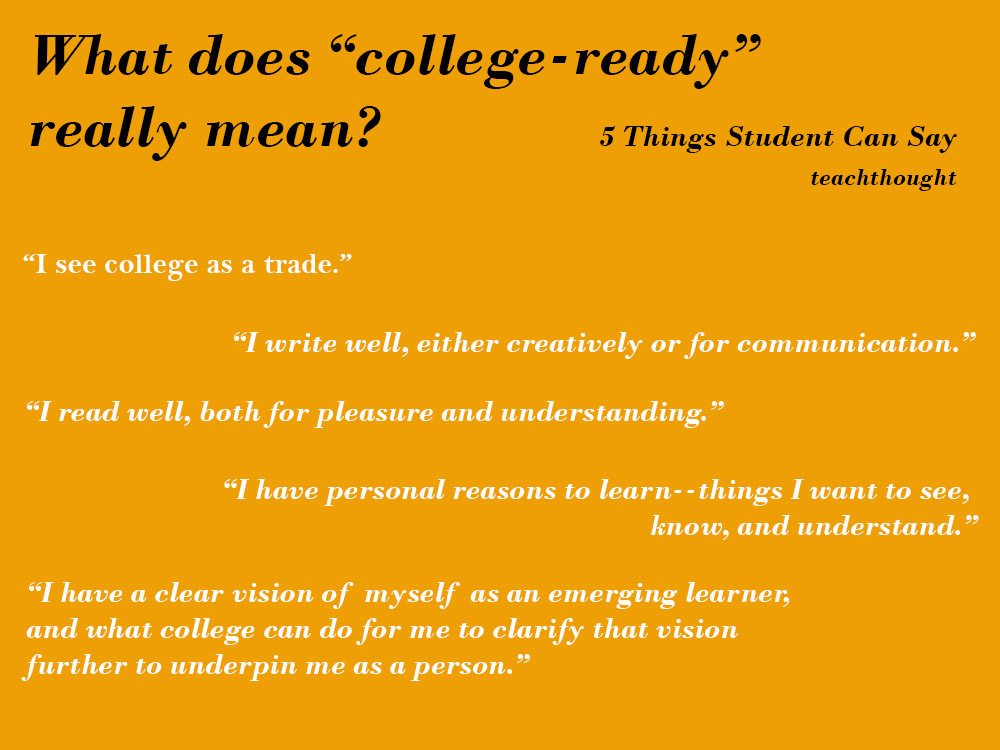

What A College Ready High School Student Can Say

So then, how can we recognize those students who might apply to, be accepted by, and otherwise excel in college?

A high school student might be ready for college when they can say:

- I read well, both for pleasure and understanding.

- I write well, either creatively or for communication.

- I understand how to research, extract key information, and evaluate its credibility and utility.

- I have personal reasons to learn–things I want to see, know, and understand.

- I see college as a trade–4-8+ years and X amount of dollars in exchange for something else. If that’s a good trade or a bad trade depends on my own measures that are personal to me and only me.

- I can either manage money, or am perma-funded by my parents or endless scholarships and loans that will drown me in debt.

- I am not scared of testing–or at least can test somewhat successfully.

- I know that people will project their thinking about college on me–what I should study, what’s “valuable,” why I should go, which one I should go to, etc. And that the more of this thinking I casually inherit (rather than think about and adopt), the more dangerous the takeaways.

- I have a clear vision of myself as an emerging learner, and what college can do for me to clarify that vision further to underpin me as a person.

- I can create and cultivate learning networks full of experts, mentors, peers, professionals, and educators.

- I can distinguish a teacher that’s there from a teacher that cares, and then get the best from each. (Because like it or not, teachers still dictate the terms of a student’s success in college no matter how motivated or demotivated a student might be.)

- I realize that knowledge precedes–and proceeds–vocation, and that the person precedes the knowledge.

If they can’t say these things, then they need to be able to say, with great certainty, “I have no idea what college is or why I might need it, but I trust myself to persevere and figure it out along the way.”

Or not go, and find their own path to their own good work.

What Does “College-Ready” Really Mean, Anyway? image attribution flickr user iksme