All About Feedback Loops In Learning

by Terry Heick

A feedback loop in learning is a cause-effect sequence where data (often in the form of an ‘event’) is responded to based on recognition of an outcome and that data is used to inform future decisions in similar or analogous situations.

In everyday life, feedback loops for each of us occur naturally–usually in the form, ‘When I do X, Y happens.’ That’s a kind of feedback loop in the learning process.

In fact, it’s at the core of the learning process and how the human brain learns.

The Definition Of A Feedback Loop

Feedback loops are important parts of machines, electrical circuits, computer coding, statistical analysis, and economic processes but are often associated with geoscience and natural ‘systems’–namely biological processes from evolutionary science to cellular biology, ecosystems, and more.

For our purposes, let’s focus on the human brain as a kind of computer. So rather than think of a person learning, we’re going to think of a brain learning. The brain is a kind of computer where input becomes output. The processes through which this occurs are largely predictable. The brain has identifiable qualities (such as the cognitive load theory) and characteristics that, as teachers, we have recognized and use to help students learn more effectively.

Critical in understanding feedback and feedback loops is understanding the structure and shape of them, something I’ll cover in a separate post. For now, let’s focus on a broad definition so that we can begin to understand their role in learning. Later, we can look more closely at the different types of feedback loops and their distinctive shapes, and then follow that up with strategies for implementing them into your classroom, curriculum, instructional design, eLearning, and other related areas.

According to Wikipedia, in a feedback loop, the ‘feedback’ occurs when “outputs of a system are routed back as inputs as part of a chain of cause-and-effect that forms a circuit or loop.”

This is true because of the nature of these systems as self-regulating. The article continues, “A feedback loop is the part of a system in which some portion (or all) of the system’s output is used as input for future operations. Feedback loops can be either negative or positive. Negative feedback loops are self-regulating and useful for and maintaining an optimal state within specific boundaries.”

See also What Is Social Learning?

Four Steps Of A Simple Feedback Loop

A feedback loop is the part of a system in which some portion of that system’s output is used as input for future behavior. Generally, they have four stages.

Step 1: The learner receives ‘input’—as an external stimulus or observation of some kind, for example

Step 2: That input is stored as data

Step 3: That data is analyzed and conclusions are drawn by the learner

Step 4: The learner anticipates future application of those takeaways in future decisions

That’s a feedback loop.

And that feedback loop—coupled with an ongoing and fluid system of increasingly complex pattern recognition—is how the human brain learns.

Five Basic Examples

So, how about some simple examples of very basic feedback loops?

When I go to bed early (the event), I feel well-rested (the outcome).

When I flip a light switch on (event), the light comes on (outcome)

When I touch something hot (event), I burn my hand (outcome).

When I don’t pay a bill on time (event), I am charged a fee (outcome).

When I eat poorly (event), I gain weight (outcome).

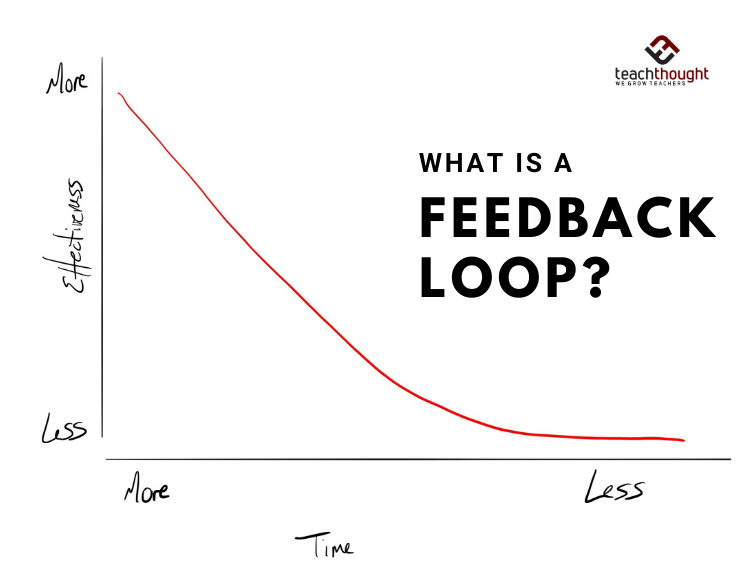

The Timing Of Feedback Loops

Generally speaking, the shorter the duration of time between an event and a learner’s recognition of that ‘event’, the more effective the loop is for learning.

The last example above is useful in understanding this and the general importance of timing in effective feedback loops.

When I eat poorly (event), I gain weight (outcome).

The outcome is ‘data’ that you can use to inform future behavior. When you eat poorly, you don’t gain weight right away. For most people, it takes weeks or longer for poor eating habits to result in observable, sustained weight gain. This makes the cause-effect less noticeable and even when it’s ‘known,’ the psychological effect of the ‘knowing’ is reduced.

Consider a slightly ‘tighter’ feedback loop: When I eat spicy food, I experience heartburn. The duration is shorter, which makes the behavior easier to adjust.

Or, consider an example even more direct: When I eat hot food, I burn my mouth. This ‘learning feedback’ here is almost instant. As far as effective learning experiences go, it’s about perfect.

And so it’s easy to see how extraordinarily effective well-timed feedback is in learning. You avoid hot food because the pain is immediate and memorable even though the impact on your health and well-being is generally worse than a minor burn on your tongue.

For weight gain, the feedback loop is just too indirect and ‘loose’ to hold our attention without strong discipline–or healthy habits to begin with that don’t require moment-by-moment ‘discipline.’

For feedback loops to be effective, a lot of other elements have to exist–cues, observation, recognition, and memory among others. I’ll write more about these soon.

As far as what this looks like in your classroom, that’s also a much longer topic I’ll address in a follow-up post, but for now, consider how you respond to student behavior, respond to writing, or grade quizzes and exams.