What Is The Purpose Of A Question?

by Terry Heick

What’s the difference between a good question and a bad question?

It depends, of course, on who you’re asking. But it also depends on both abstraction (i.e., the concept of ‘good’ and ‘bad’) and function (i.e., purpose).

You can’t, for example, measure the ‘quality’ of a ‘thing’ without knowing its standard or purpose or intent. To be able to say that someone gave you ‘good’ directions would require that A) the purpose of directions is to help you arrive somewhere you wouldn’t otherwise be able to without explanation and B) that the directions either did or could have enabled that to happen.

The same with anything else–cars, apps, books, dancing–but the more we leave pragmatism behind in search of abstraction, the less objective and clear our definition of ‘good’ likely is; it’s easier to say with confidence that a recipe’s instructions were good than the result of that recipe (i.e., the food) because in-between the recipe and the result (i.e., the cause and the effect) is human fallibility. Or just plain human nature.

Back to the difference between a good question and a bad one: What’s the purpose of a question? Never mind the aesthetics of the thing–what’s it supposed to do?

The Difference Between A Good Question And A Bad Question

Let’s first clarify our terms for now and agree to evaluate quality as merely ‘good’ or ‘bad.’

You likely have grades to grade, assessments to assess, and data to data-lyze, so let’s get straight to the point: For teachers, a ‘good question’ can be considered ‘good’ if it does what it’s supposed to do. And it’s really that simple.

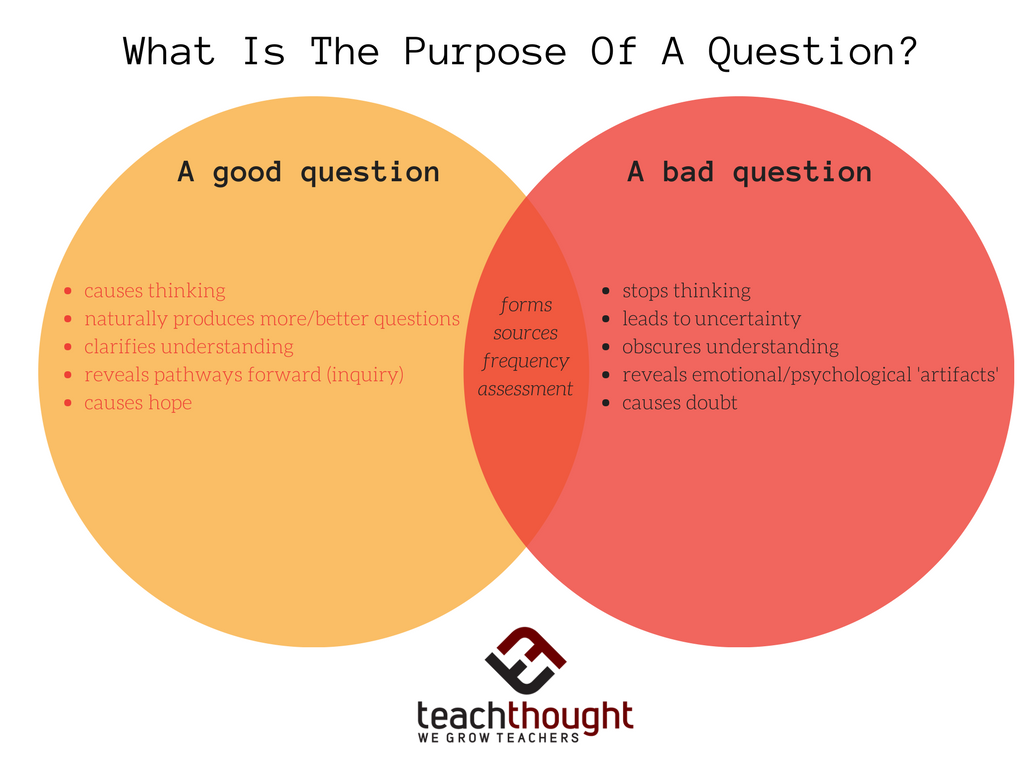

To be a little more abstract, a good question causes thinking–more questions. Better questions. It clarifies and reveals. It causes thinking, reflection, reconsidering, and maybe even a kind of hope.

A bad question stops thinking. It confuses and obscures. It causes doubt.

What Is The Purpose Of The Question?

Let’s look at what questions ‘do.’ Two of the most common functions of a question are to assess knowledge (evaluative) or cause thinking (rhetorical). This can be further drilled down into (a nearly infinite number of) subcategories:

Evaluative Questioning

Purpose: to assess knowledge

to assess strength/depth of knowledge

to identify gaps in knowledge

to identify the ability to transfer knowledge

Rhetorical Questioning

Purpose: to cause thinking

to cause thinking to cause emotion (for effect)

to cause thinking to cause further/extended thinking

to cause thinking during dialogic interactions

If the first step in evaluating a question is first understanding its purpose, the second is making sure it achieves that purpose. If it doesn’t, it’s ‘bad.’ (See also 8 Strategies To Help Students Ask Great Questions.)

(Note: not all questions exhibiting these characteristics are ‘bad’ and not all bad questions exhibit these characteristics. This is just a general overview of ‘questions that could be better.’)

8 Characteristics Of A Bad Question

1. Whether Evaluative or Rhetorical, the purpose of the question is unclear or it doesn’t achieve that purpose (e.g., the question isn’t aligned to a learning objective)

2. The question ‘centers itself’ and/or distracts from the content or thinking; the question is self-referential and self-centered

3. An abnormally high % of students miss the question (though the opposite isn’t necessarily true)

4. Students that have demonstrated mastery of the content/standard in other ways ‘miss’ or otherwise ‘perform/respond poorly’ to the question

5. The question seems to ‘halt’ or radically slow the learning/inquiry process

6. Successfully ‘answering’ the question doesn’t yield much more than having ‘gotten the question right.’

7. The wording of the question is confusing or unnecessarily complex (see #1)

8. The question doesn’t agitate students intellectually or move them emotionally

The Characteristics Of A Good Question

1. The question achieves a clear purpose (whether Evaluative or Rhetorical)

2. The question illuminates the nuance of existing knowledge (as opposed to limits itself to whether or not a student can ‘answer it’ or not), revealing either the genius of the content or the genius of the student

3. The question encourages understanding and transfer, not ‘success and performance’; it leads to extended and/or deeper thinking

4. The question lends itself well to its own refinement and improvement, or better questions altogether

5. The question (more often) comes from the student, not the teacher

6. The question causes positive emotion (again not all questions that do are good and that don’t are bad–these are just general principles) and/or useful connections (inter-personal connections between students, inter-content questions between bits of content, etc.)

7. The question requires students to synthesize multiple perspectives or interpret and unify multiple sources of information to create a quality response

8. The question can be answered in multiple ways

Good Questions In The Classroom

To summarize, if you’ve clarified the purpose of the question (e.g., Evaluative vs Rhetorical), all that’s left for you to do is to improve its quality.

But what makes a question ‘good’ in the ‘real world’ is a bit different than in school because of the roles assumed in most traditional classrooms. In the real world, good questions tend to be thought of as such because of their effect (e.g., if the person answering can’t do so, or it frames old information/circumstance in a new light, we might say ‘That’s a good question.)

In the classroom, students are typically burdened with proving what they know, so questions that imply that they ‘get it’ and don’t (identifying knowledge gaps and yielding ‘useful data’) are considered ‘good.’

To really create a climate of critical thinking in your classroom though, there has to be a shift from teachers and what they want to see to the student and what they want to ask. Questions are often considered more important than answers not in celebration of esotericism, but because they reveal so much. What students ask—when they do, in fact, ask—can be illuminating.

If, during the study of the Civil War, a student asks when a battle occurred, we can sense that they are trying to make sense of a detail. If they ask why soldiers fought a certain way, they are trying to make sense of strategy.

If a student doesn’t ask anything at all–well, this could ‘reveal’ a lot of things. It could be a lack of background knowledge or confidence or engagement, or that there really is no room or need for them to ask–or just that they’re assuming a passive learning role at the moment.

If they ask why the war was fought, they’re making sense of very complex macro concepts, including cause and effect.

If they ask ‘why they have to know this,’ they’re unclear on the utility of the content.

If they ask ‘Is this going to be on the test?’, they’re concerned with academic performance more than the content itself, much less critical thinking and inquiry.

But another reason these questions are good is due to the source and purpose: a student clarifying their own confusion or following their curiosity. An answer is a kind of culmination or performance–an ending, while a question is a beginning that could lead anywhere.

Questions are the pulse of any critical thinking classroom. The source, frequency, and quality of questions (not answers) in your classroom are among the best sources of data available to any teacher of any grade level and content area.

Other Notes

There are some things good and bad question share in common, including:

forms (e.g., multiple-choice, open-ended, true-false, etc.)

sources (e.g., students, teachers, curriculum developers, etc.)

frequency (e.g., by the minute, per class, daily, weekly, etc.)

…and finally, their most visible purpose and context, assessment.