David Foster Wallace Taught Students To Respond To One Another’s Writing

by Terry Heick

One of my favorite genres of writing is the essay, and an essayist I enjoy is David Foster Wallace.

Wallace–or DFW if you’re okay with that–was equal part non-conforming, angst-ridden rebel and submissive lover of formal language and all of its rules and sentence-diagramming splendor. He was Jay Z and Strunk & White and Mark Twain all rolled into one, which made his writing a dizzying mix of all that as well.

Footnotes paragraphs, paragraphs pages long, novels a thousand pages long. Essays about tennis and state fairs and corn and hip-hop and academia and depression and cruises and the depressing and mesmerizing nuance of human existence all part of his muse.

With this kind of diverse background, his maniacal love for grammar and word choice and the precision of syntax and the right word fits right in, especially if you see language as a way to place rules on the species that has a way of bending them spectacularly. Language is a sort of caging and framing of the mind, which would annoy anyone who sat down and thought about it for long enough; it is somehow both volatile and impossibly sedate.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, DFW also dabbled in the teaching of writing. His mother also a professor, he was a TA at the University of Arizona in 1987, an adjunct professor at Emerson College in 1991, and most recently teaching English 183D Pomona in 2008 College. Recently, an anthology of his work was collected in the form of the David Foster Wallace Reader, a book I didn’t know I couldn’t live without. A sample? DFW explaining the idea of creative non-fiction.

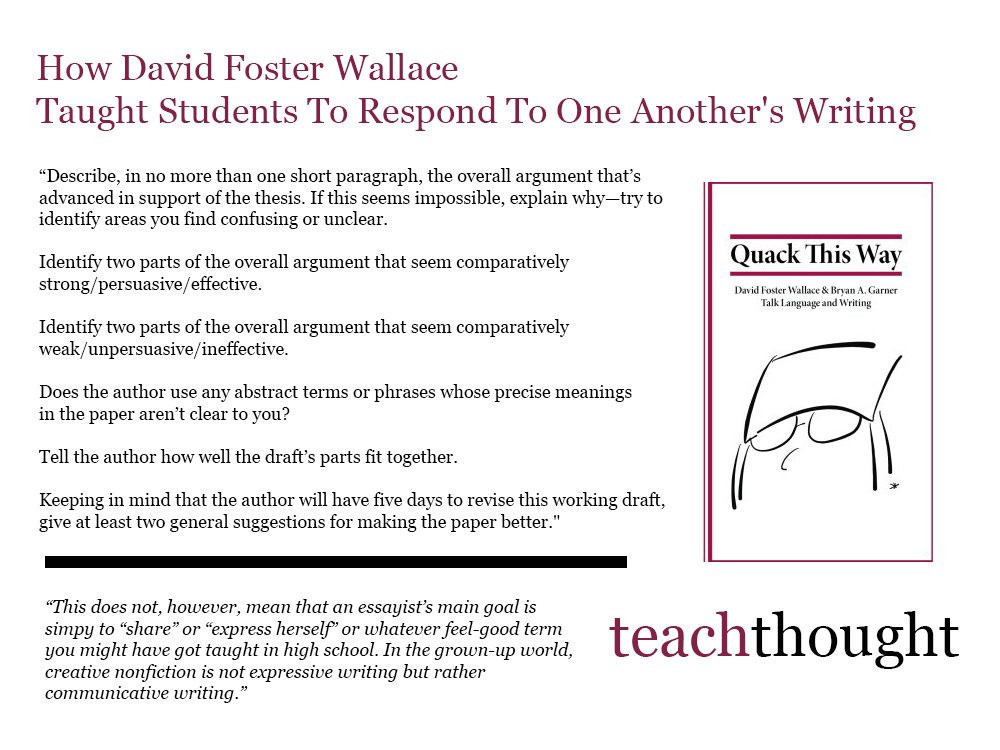

“Creative also suggests that this kind of nonfiction tends to bear traces of its own artificing; the essay’s author usually wants us to see and understand her as the text’s maker. This does not, however, mean that an essayist’s main goal is simply to “share” or “express herself” or whatever feel-good term you might have got taught in high school. In the grown-up world, creative nonfiction is not expressive writing but rather communicative writing. And an axiom of communicative writing is that the reader does not automatically care about you (the writer), nor does she find you fascinating as a person, nor does she feel a deep natural interest in the same things that interest you. The reader, in fact, will feel about you, your subject, and your essay only what your written words themselves induce her to feel.

So often students are taught how to write, but not why, and certainly not what’s possible. And if you read DWF long enough, if you find nothing else, you’ll find a timeless index of what’s possible when your focus is on the craft of writing.

Teaching Students To Respond To One Another’s Writing

Among the sections is one on teaching, which I was surprised to find (being that there’s an entire section devoted to it, and his interest in formal education rarely surfaced in his writing). While the “DFW Syllabus” is better-known (we’ll look at that another time–Google it if you’re curious), in the reader is also included a series of questions to act as a guideline for students to respond to one another’s writing.

It is both academic and authentic; it is practical and thoughtful; it is focused on writers, and on readers. In short, it acts as a wonderful distillation for DFW in general, and a potentially tool for you to consider as you teach the craft of writing in your own classroom. Helping students respond to one another’s writing in a meaningful way isn’t easy at any grade level.

More than anything else, he focused on specific elements of the craft of writing in a way that is very personal. Are the ideas interesting? Is language unclear? Does the writer seem to be doing this or this? Your partner really needs you for this, etc.

I hope, then, you find DFW’s approach to writing response useful.

“The David Foster Wallace Reader

November 11, 2014

Specs and Guidelines for Peer-Review Missive

1. Identify what appears to be the present draft’s thesis or overall point. If you aren’t sure just what it is, list the most likely possibilities.

2. Tell the author whether her thesis is interesting to you or not. Like, whether it adds anything substantive to your own reading(s) of the novel(s) in question. If it doesn’t, you might suggest ways to make the thesis more interesting.

3. If, on the other hand, the overall thesis seems to you implausible, or unconvincing, or if you can see serious objections to it that the author hasn’t addressed, tell her about them.

4. Describe, in no more than one short paragraph, the overall argument that’s advanced in support of the thesis. If this seems impossible, explain why—try to identify areas you find confusing or unclear.

5. Identify two parts of the overall argument that seem comparatively strong/persuasive/effective.

6. Identify two parts of the overall argument that seem comparatively weak/unpersuasive/ineffective.

7. Does the author use any abstract terms or phrases (e.g., “despair,” “gender,” “happiness,” “discover who she is”) whose precise meanings in the paper aren’t clear to you?

8. Tell the author how well the draft’s parts fit together. Is she doing a good job of moving the reader coherently from one part of her argument to another? If not, try to identify some places where you get disoriented or couldn’t figure out where in the discussion you were.

9. Tell the author whether her use of quotations from the novel(s) and or secondary sources seems effective. Do some of the quotations seem stuck in merely to satisfy the “Research” requirement? Are any quotations unnecessarily long? Are quotations introduced well, woven smoothly into the author’s own prose, or do they just seem to hang there awkwardly? If you’re already conversant with MLA format, are the quotations cited correctly?

10. Identify (in the margins of the draft if not in the letter) any basic syntactic errors you spotted that violate the Dept. Format and Style Sheet, or that have been covered in class during the semester. (Since final drafts that contain these sorts of errors will be severely penalized, you have a chance to do your partner a real service here.)

11. Keeping in mind that the author will have five days to revise this working draft, give at least two general suggestions for making the paper better.”