A Writing Strategy That Works For Every Student, Every Time

by Terry Heick

Writing is difficult to teach, if for no other reason than it is also difficult to do.

Put simply, writing is the documentation of thinking. Because it’s been done in so many different formats for so many different reasons for so many years, writing has become extraordinarily nuanced. Readers are conditioned not to just decode and interpret, but to recognize the purpose of even the most mundane choices–in diction, for example.

See also What’s The Writing Process?

That there is a marked difference in aesthetics and tone between ‘O.K.,’ ‘OK,’ Ok,’ ‘okay,’ ‘k,’ and ‘k.’ (lowercase ‘k’ with a period after to more abruptly stop the thought) underscores the versatility of language–written or otherwise.

Then adding in the truth that writing isn’t a single act but a sequence of acts–and thus a process–writing becomes complex to teach, and writing well becomes nearly impossible to do anything but vaguely describe and encourage.

As teachers of writing, we can only say, ‘Here are some things great writers do, so let’s pick a few of those things to practice and see what happens, and then I’ll grade your attempts. Sound fun?’

While writing is incredibly complex, like any act, its success must be measured most broadly by clarifying its effect: what is it supposed to do?

It’s difficult to evaluate a school unless we know what a school is supposed to do. Even if there’s no single standard, there has to be some kind of agreement on function and purpose.

How can we assess the economy as ‘doing well’ or ‘doing poorly’ without knowing what an economy is supposed to do? What it’s capable of, and how it’s intended to function? The same with a politician. Or a coat. Or an app or the accuracy of a meteorologist. ‘Good’ and ‘bad’ are worthless descriptions without some kind of ‘standard.’

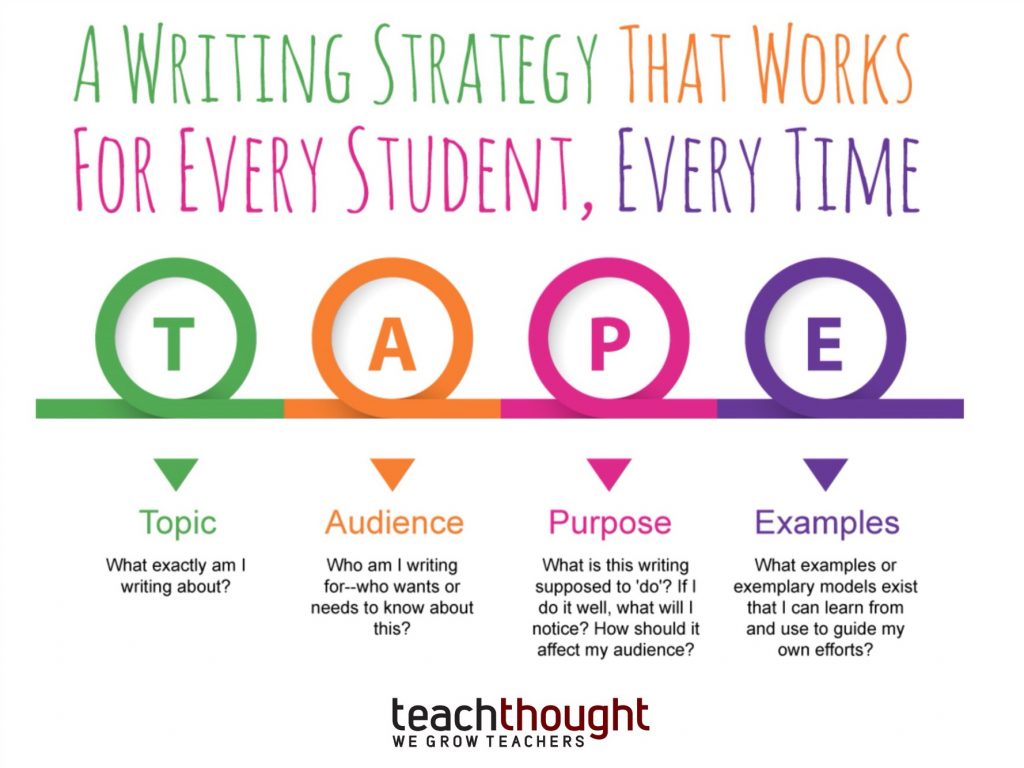

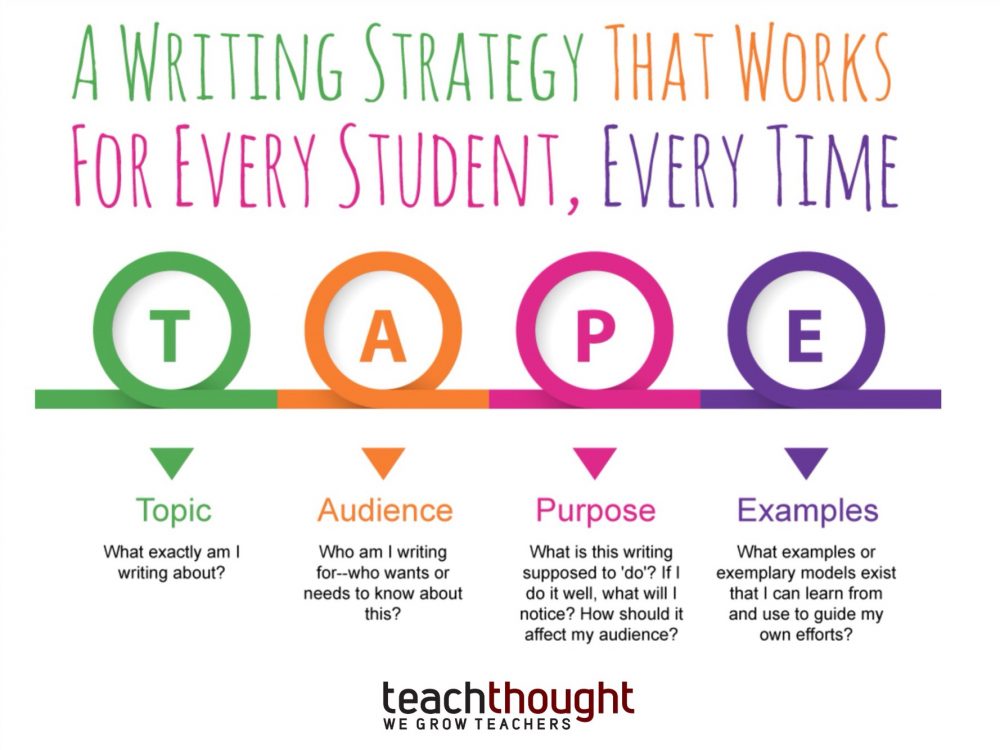

A Pre-Writing Strategy That Works For Every Student, Every Time

In writing, TAPE is simply a way of clarifying what you’re doing before you do it—or a way to help writers.

Topic: What exactly am I writing about?

Audience: Who am I writing for–who wants or needs to know about this?

Purpose: What is this writing supposed to ‘do’? If I do it well, what will I notice? How should it affect my audience?

Examples: What examples or exemplary models exist that I can learn from and use to guide my own efforts?

It obviously can get way, way more complicated than this, and depending on who you’re teaching writing to and why, you and your students may need to grapple with that complexity.

Form, idea organization, structure, transitions, tone, mood, syntax, pathos/ethos/logos, publishing platforms…

You can simplify it if you’d like–TAP:

Topic/Theme/Thesis: Immigration, freedom, symbolism, sentence structure, growth mindset, metacognition, etc.

Audience: Who wants or needs to know, obviously varying wildly by topic

Purpose: To inspire, to inform, to persuade, to reveal, to reframe, to expand, to draw attention to, etc.

A Pre-Writing Strategy That Works For Every Student, Every Time