How To Teach With Art In Any Subject Area

contributed by Nicola Giardina

Art inquiry is a powerful way to engage students with diverse learning needs, improve critical thinking and social-emotional skills, and make learning relevant to students’ lives.

Yet many teachers shy away from teaching with art, which causes their students to miss out on these potentially transformative learning experiences. Teaching with art creates opportunities for novelty in the classroom, stimulating students’ minds and activating different ways of thinking and learning.

In my work with teachers, I always emphasize that teaching with works of art doesn’t require specialized knowledge in the field of art. It does require the willingness to look at your curriculum through a creative lens to find new and unexpected connections to the content you teach. If you are looking for a way to enliven your curriculum, the five steps below will help you leverage the power of art to improve your teaching practice and students’ learning.

1. Choose a Work of Art

Because art tells the story of human history, there is no curriculum topic that works of art can’t support. With your curriculum in mind, explore museum websites. A great place to start is The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s website, metmuseum.org, where you can download high-resolution images of thousands of works of art from their encyclopedic collection. Brooklynmuseum.org and moma.org are also excellent resources for art images. When selecting works of art to teach from, consider these three questions:

- Does this artwork spark my interest?

- How does it relate to my students’ lives?

- How does it relate to our curriculum?

If the work of art you choose satisfies all three of these criteria, you have the foundation for a successful art inquiry experience.

2. Think Thematically

Use a theme or essential question to support connections between the work of art, your students’ lives and your curriculum. Effective themes and essential questions are intellectually engaging and universal; they provide an entry point into challenging content by supporting personal connections between students’ experiences and academic content. For example, a middle school teacher used the theme “Friend or Foe?” to support her students’ study of John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men.

In the classroom, she showed her class portraits in which the artist and the subject had a complicated relationship. Exploring the theme through the paintings while connecting to their own lives deepened her students’ understanding of a central theme in the novel.

See also What A Thematic Unit Looks Like.

3. Develop Open-Ended Questions

Open-ended questions inspire critical and creative thinking. By engaging your students in open-ended inquiry with works of art, you affirm their unique ways of seeing the world while teaching them to value the diverse viewpoints of their classmates. To ensure your questions are open-ended, challenge yourself to think of multiple responses to each question.

If you can come up with at least three possible responses, the question is open-ended. If you expect one ‘correct’ answer, the question is closed. Try rephrasing the question to make it open-ended. Your questions should also encourage close looking by requiring students to use visual evidence to support their ideas. This will ensure that the conversation remains grounded in the work of art.

For resources and tips here, see our Updated Guide To Questioning In The Classroom.

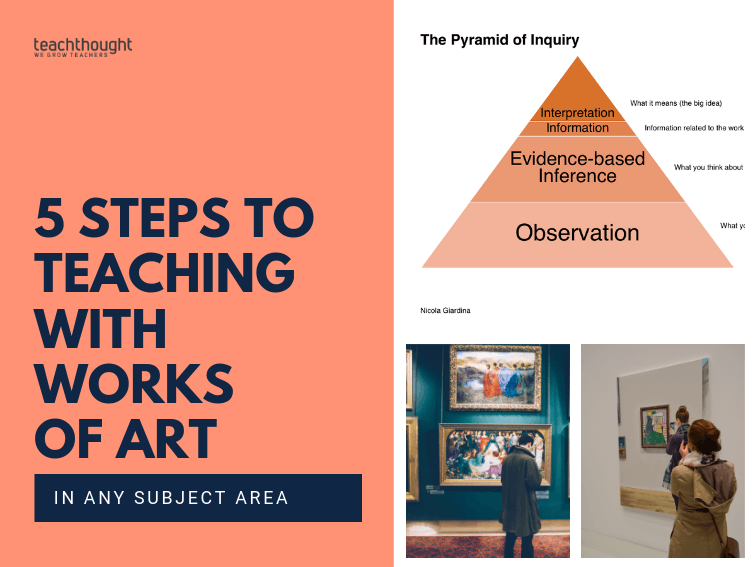

4. Use the Pyramid of Inquiry to sequence your questions

The Pyramid of Inquiry is a flexible framework that can be used with any work of art to facilitate inquiry experiences that develop critical thinking skills. The foundation of the Pyramid is observation: students begin by looking closely through an open-ended prompt such as, ‘What do you notice?’ or a multimodal approach such as sketching the object. Observation is the critical first step in the inquiry process because the information gathered in this phase will support the development of inferences and interpretations that are grounded in visual evidence. The next level of the Pyramid is evidence-based inference.

See also Stop Looking For New Tools And Start Looking For New Ideas

This could be prompted by a question along the lines of ‘What’s going on in this painting’ or a movement activity that asks students to take the pose of a character in a painting and infer how the character feels, using evidence from the artwork to support their ideas. At this point, you will introduce relevant contextual information about the work of art. Once students have absorbed this information, the conversation builds to the interpretation phase, where students synthesize this new information with their previous ideas about the work of art.

Interpretation can involve a big question such as ‘What do you think is the message of this work of art?’ or an art-making activity that asks students to express the meaning of the artwork in a creative way.

5. Expand learning beyond the classroom

Whenever possible, bring students to a museum or gallery to explore works of art in person. These kinds of experiences yield powerful results for student learning (Greene, Kisida & Bowen, 2014), and seeing a work of art in person is a vastly different experience than viewing it on a screen. Reach out to the museum’s education department before you visit; they exist to support teachers and students and offer a wealth of resources to support your teaching. If museums and art galleries are not abundant where you teach, seek out local artists. They can be a rich source of information for your students and are often happy to take time to speak with young people about their work.

Finally, a word of encouragement: if you are new to art, don’t be intimidated! Use art inquiry as an opportunity to model creative risk-taking with your students. You will be rewarded with the gift of seeing works of art, and your students, with fresh eyes.

Nicola is the author of The More We Look, the Deeper It Gets: Transforming the Curriculum through Art.