How To Remove Poor Gamification From Learning

by Terry Heick

This post has been updated and republished

Leaving the classroom and becoming whatever it is that I am now has been a humbling experience.

I never grew up wanting to be a teacher, and didn’t even consider the possibility until I was almost 30 years old—and only then because I loved literature and writing and literacy and digital media and the increasingly tenuous but critical relationship between them.

So I was never pulled to teach through any sort of a calling or legacy. My parents were photographers, and my grandfather (law school) was the only person in my family to ever graduate from college. School was always an awkward kind of place for me. I did well academically, but from a purely human perspective, it was rough. I was introverted and sensitive and had trouble seeing myself in relation to others (still do), and the dissonance there gouged all kinds of fun insecurities for me.

And let’s be clear: school is first and foremost a social experience—and a thoroughly gamified one at that. Points for this, rules for this, letter for this, awards for that, motivation for this and this and demotivators for that. And when it’s all over, line them all up in descending order from valedictorian backward and tell them that’s the way the real world is.

The Gamification Of Life

Only, of course, it isn’t. Resiliency factors and ethics and charisma and a sense of self and purpose—and a dozen other factors–all matter a lot more than academic proficiency in terms of ‘college and career readiness.’ And somehow, reductively, that’s the postmodern vision for school—college and ‘career’ prep, which is horrific when you consider the growing popularity of competency-based education in the post-secondary world where the companies actually work with the colleges to tell them exactly what students should be learning in order to get a job at their corporation and no-one-seems-bothered-by-this-like-it’s-all-part-of-the-game.

Corporations handcrafting the education of human beings.

So, back to the social and gamified experiment that is school. Academic success and failure are hugely visible to everyone no matter who has access to the grade book. By the first week of school, it’s apparent to everyone where they stand in the classroom, first with one another, then with the teacher. I’m good at this, not good at this; willing to try this, but probably not going to reveal too much of myself here and here. I need to know the points so I can learn the bare minimum I need to do to survive while maintaining my self-image (or what’s left of it).

So most students know—or are learning–their lane and how to stay in it. You’ll be able to shift the habits and self-confidence and skill levels of the students, but a few days in, the game is set and the rest of the year is a matter of playing that game.

While you can’t remove the social part–nor would you want to–you can do something about the gamification part. Some of these elements may be less accessible to you than others. This is the game–and there are rules to that game that are deeply entrenched in the permafrost. These parts will stay downright untouchable until other competing systems of learning make them obsolete. But at least we can stare at them through the ice and wish they weren’t there.

Gamification Isn’t A Bad Thing

Note, I’m not arguing against gamification. In fact, I think it has significant potential in education. We’ve written before about adding gamification to your classroom–a few examples:

A Human Framework For Human Motivation

How Gamification Uncovers The Nuance Of Learning

But if you want to be more aware of what gamification is and how it’s working in your classroom, some of these quick examples might be useful if for nothing else than to be more intentional for how you do use it.

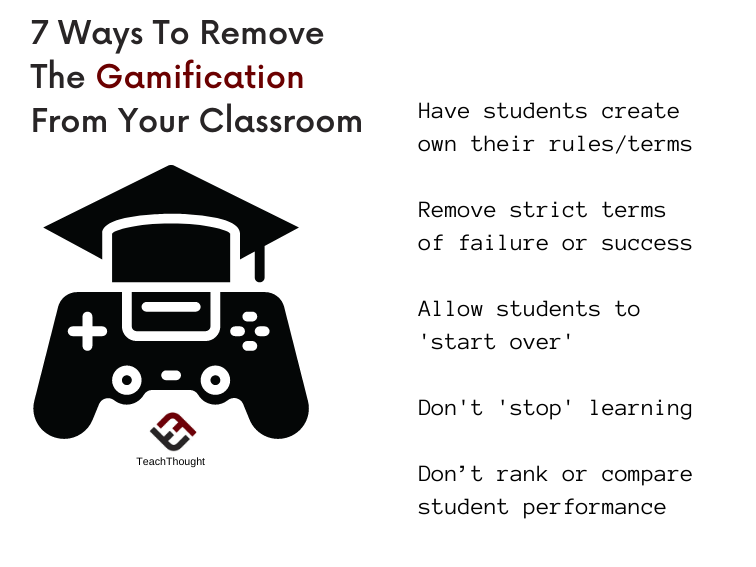

7 Ways To Remove The Gamification In Your Classroom

1. Have students create own their rules/terms

For an assessment, a project, an assignment, or even whether they pass or fail. If they make the rules, while there is still a game, they’ve had a hand in creating it.

2. Remove strict terms of failure or success

No minimum numerical value to pass–focus instead on progress, change, tactics, strategies, quality, iteration, and action.

Traditional game design is about playful barriers for players to achieve goals. It’s obviously experiential and constructivist. Early video games were more ‘pass or fail’: you either ‘beat the game’ or you didn’t. You finished the level or ran out of lives. Modern video games are focused more on an ongoing experience where players, over time, accrue experience and craft characters and journeys that fit their vision for the game.

3. Remove letter grades altogether

We have them because they’re iconic symbols that express academic success in a language everyone understands–but because of this universal-language-ness, they’re reductive, hurtful, and artificial. There are alternatives to letter grades, after all.

4. Remove artificial start and stop times

Instead, strive for always-on learning–like intellectual start-ups that are open 24/7. Chain units together beneath one comprehensive question or challenge. Only give ‘points’ for improvements to existing work, and constantly raise the quality bar so it’s more difficult each time to get the same credit.’

Life doesn’t stop by simulations of life do. So do more of the former than the latter.

5. Allow students to ‘start over’

This one is really making learning more like a game than less, but here it is nonetheless. If you’re not keeping score, every day is new. No such thing as a summative assessment. It’s all formative. And informative. Give them the space or flexibility to work from a clean slate whenever possible, even if they keep ‘failing.’ Instead, change the terms of failure.

6. Don’t rank or compare student performance

Yes, I know norm-referenced assessments rank students, as can criterion-based assessments. And yes, I know “the real world” will rank them. And so will colleges. Why are we in such a rush to introduce the heartbreakingly-broken ‘real world’ to precocious young minds that are trying to find their rhythm?

7. Remove points

No numbers or points–these are just symbols. Find a more personal way to give learning feedback.

Removing Gamification In Your Classroom