A Process For Planning The Genius Hour Design Cycle

contributed by Nigel Coutts

In an ongoing effort towards polishing the edges, over the years we have continued to refine the processes we apply to the Personal Passion Project.

We have gained insights into the sorts of projects that work well and which will cause difficulties. We have added a degree of structure while maintaining the required degree of freedom necessary for a personalized project.

The results of this learning are presented (in the model above and the text) below.

1. Be prepared to be amazed

The quality of the students’ projects will go beyond what you expect. This is particularly important when a student comes to you with a grand idea that seems too hard or overly complex. If the student has the right level of passion for the project and an idea for how they will get started they will more than likely complete the project and complete it well.

2. Don’t let your fears get in the way

The students are almost certainly going to select topics that you have no knowledge of and don’t have the skills to support. At this point, it could be easy to let your fears and insecurities get in the way.

The best way to move forward is to listen to the student; do they know what they are doing? do they know which questions they need to answer? what problems do they need to solve? If the answers to all of this are positive, start looking for an expert to help when times get tough.

3. Some students need a push in the right direction

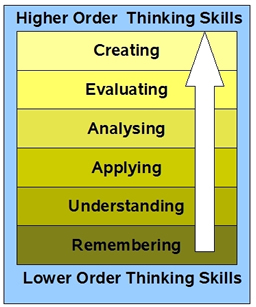

Some students will come up with projects that are too simple with answers that could be easily Googled. We introduced the students to ‘High Order Thinking Skills’ and built these into the planning forms students complete. Projects need to include elements of synthesis, evaluation, and creativity with the minimum requirement adjusted for individuals.

We provide students with a list of verbs appropriate for the top levels of Bloom’s taxonomy and help them use these in framing their topics.

4. Some students design a project that has nothing to do with their passion

A student might have a passion for surfing and decide they are going to write a book about the history of the sport. The problem is they have designed a project where they will need to be a historian, a researcher, a writer and you know they don’t enjoy doing any of this. Maybe with the right topic, they will gain a wider interest in these things but most likely they will quickly dream of days at the beach.

5. Some projects are just not possible

It can be hard to say no to a project but some are just not feasible. A classic example is a student who wants to design a better tennis racquet by selecting the right mix of shapes and materials. The problem is that the modern tennis racquet uses high tech composites and even with million-dollar R&D budgets the differences between one design and the next is hard to prove.

6. Time & Scale

Some projects will clearly take longer than you have available, others are simply too large in scale or will rely on the involvement of too many people. Setting manageable goals and working to an achievable timeframe is important. At the same time, you need to ensure that the concerns over time constraints are genuine.

Creating a detailed timeline with estimates of how long each phase will take is beneficial on many levels at this stage. For the students, the conversations around how long the project will take can include some rewarding reflection on how they approach tasks and can assist in their development of an understanding of their learning style.

Some students need time to talk about their project and unpack ideas socially, others need quiet time to think through the steps, some just dive in and fix mistakes and redirect their plans as they go. (See Learning Lessons From Albert Einstein for more ideas here.)

7. Too many changes

One of the challenges for some students has been the ever-changing project. They select one topic, discover they don’t like it, or encounter a problem they can’t easily solve and change to another topic. A week later and the process repeats. Setting a definite deadline after which there can be no changes is important. In the end, the students work out that they have to make their ideas work.

8. Just enough planning

Over the years we refined the level of planning the students were required to do before commencing on their projects in earnest. The initial version required great detail and length processes for developing focus questions and setting targets.

For some students and some projects, it worked well but for others it got in the way. Eventually, we got to a point where the planning had just enough detail, so we know the students have an understanding of their project and that we can support them along the way. View our simplified planning template

9. Relying on experts and building a team

Many of the projects students have explored over the years fall outside of the expertise of their teachers. I have no idea how to sew for example and have been of equally little help to students who are basing their projects around dance or music.

Across the school, we have found amazing partners with the skills we needed and in most cases, they are keen to spend time with a student who they share a passion with. Building a team of support around the project is key to its ultimate success. Being mindful of the workload within this team is also important.

We have had some colleagues so keen to help that they become overloaded and although they never complained we had to be careful in managing the demands on their time.

10. Collaboration & Self Organized Learning

Because this is a Personal Passion Project we have not included team projects. Nevertheless, collaboration between students is an important part of many projects. Where possible foster the opportunities for collaboration while allowing each student to maintain control of their project. The power of collaboration will lift the quality of the projects as students share ideas and encourage each other to go beyond expectations.

Collaboration will also solve some of the problems with projects outside the teacher’s comfort zone. This year I had a group of students focused on game development and their ultimate success was a direct result of the community of like-minded learners they created around their projects.

This is a perfect demonstration of students adopting a self-organized learning environment as they connect with their passions.

11. The invisible safety net

For the Personal Passion Project finding the right levels of scaffolding, teacher input, and guidance is one of the challenges. We want the students to feel that they are working independently while maintaining an appropriate level of support. In many ways, we are wanting to provide an invisible safety net that allows the students to take risks independently while having the support they require.

12. Documenting the process and ensuring time for reflection

Giving time to active reflection on the process has been important. Students need to be able to take a step back and assess what they have achieved and what remains to be accomplished. Sharing these ideas with peers is most beneficial and allows you to train the students in reflecting on their learning and in giving feedback to their peers.

The act of reflecting on the process has also benefitted many students when it is time to share their projects with the world as their audience is as interested in the process as they are in the product. This is particularly true for projects where the process is not obvious or is underestimated by the audience. A good example is game design projects in which the finished product does not reveal the level of knowledge and effort that was required.

13. Real Audiences

For all learning adding a real audience for the students is critical, too much of what students do is produced for an audience of one. The Personal Passion Project presenting to an audience at the end of term ‘Gallery Walk’ has been critical in ensuring the success of the projects. The students gain a real sense of achievement from this day and the feedback is always genuinely positive.

In the future, we are planning to move to a ‘Genius Hour’ model with students engaging in a scaffolded program of project management skill development throughout Semester One that leads into planning for and completing a Personal Passion Project across Semester Two. The difference will be that the learning experience will be distributed across the year, one hour per week.

We hope that this fits with the demands of the new syllabus from a time perspective while retaining the best parts of the present model. Certainly at the end of the year, we will reflect and share what has been learned.

Part 1 of this 2-part series can be seen here; note that some of the language has been slightly revised from the original post by Nigel. He uses the term passion projects, which is very close to Genius Hour and Passion-Based Learning. The differences across the three terms are often a matter of individual use and interpretation, a point we wanted to help clarify by using the three terms interchangeably even though they may not be exactly the same–passion projects needn’t use a Genius Hour format, nor does passion-based learning necessarily need to take the form of projects. In that way, the above model can be used for any of the three, but it felt most precise as a model for teachers to use to design Genius Hour projects. So, here we are. You can (and should!) read more from Nigel at thelearnersway.net.

Graphic courtesy of ©International Baccalaureate 2007.