The Elements Of A Successful Responsive Schoolwide Behavior Program

contributed by Matt Renwick

Every building has its issues with student behaviors and how to support kids who struggle socially and emotionally in school. We sometimes refer to these students as ‘frequent flyers’ as they are repeat visitors to the office. The usual reasons include noncompliance, disruption, disrespect, and physical aggression, at least at the elementary level.

Schools that focus on responsive language, common expectations, and a coherent approach to addressing behaviors usually experience success with 80% – 85% of the student body. So what about the 15% who need additional support? It’s easy to administer consequences that stop these behaviors in the short term: Detention, suspensions, even police referrals. But these are not strategies that help students over time. They are quick fixes but do not address the root of the problems that students are experiencing.

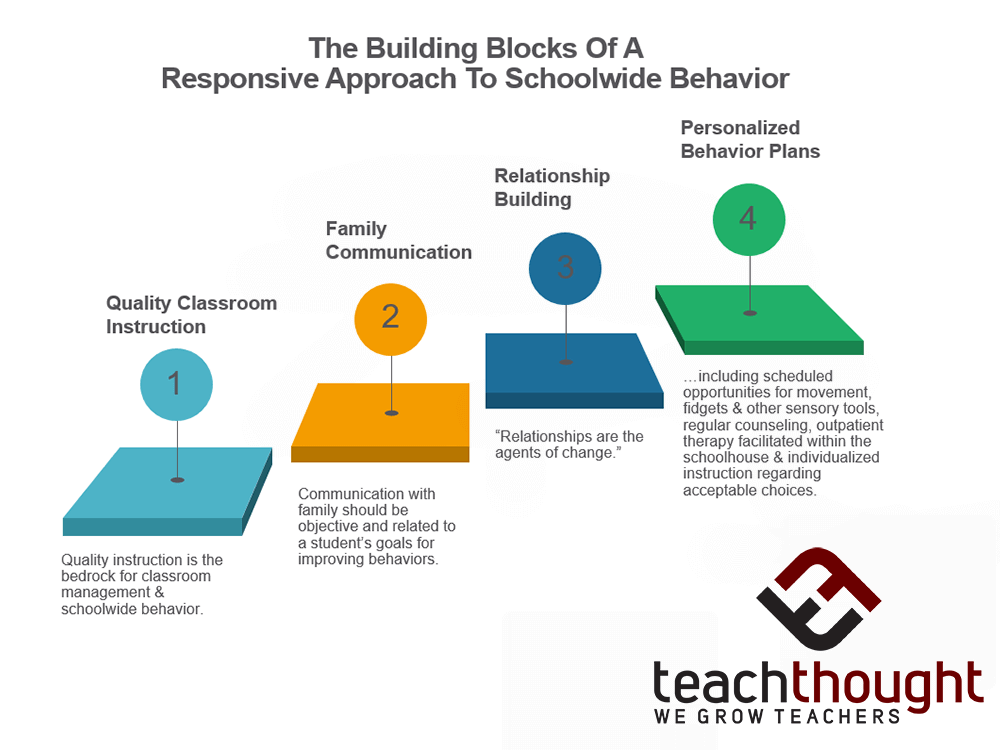

Here are four strategies our school has found to be effective for our students with the highest needs. They are not prescriptive. Schools should make informed, professional judgments about which approach(es) might best address the situation.

See also The Benefits Of Technology In Teaching And Learning

Quality Classroom Instruction

This is sometimes the elephant in the (class)room. In the case of a poor teacher, a student might be acting out because they are bored or they do not have a good relationship with the adult. It falls back on not having high expectations and/or not taking the time to build trust and a community with the students. This requires that the principal is in the classroom more often, offering coaching and feedback to improve instruction.

Also, a factor in classroom instruction is how a school places students into classrooms the prior spring. My predecessor started a process where every teacher notes the level of academic and behavioral support each student needs. This is communicated with next year’s teachers, who then place students so there is a mix of high, medium, and low needs in both areas across the grade level. Of course, this is a challenge with smaller schools.

To help monitor classroom instruction, we ask all staff members to complete an office discipline referral form in the situation of a student misbehavior. This form is not a ‘write-up’ or similar documentation that treats the student as a problem to be fixed. Staff are instructed that this referral form is a data collection tool to help us find patterns and trends in a student’s behaviors if it becomes an ongoing issue. There are consequences for student’s negative choices, but they usually only address behaviors in the short term.

Family Communication

If the instruction is of high quality and the general level of classroom community is strong, yet a student still struggles with behaviors, we have found that frequent family communication is key to seeing improvements. (We use the term ‘family’ instead of ‘parent’ because we have such a wide range of home situations where a parent is not necessarily the primary guardian.)

This isn’t simply a note going home anytime a student has a bad day. For students who fall in that 15%, families need regular feedback about how school went for their child. It should be objective and related to a student’s goals for improving behaviors. One approach we have found effective is Check in-Check Out. This is borne out of the Positive Behavior Intervention and Support system. It involves the student checking in and checking out with an adult in the building about how their days are going with regard to their goals.

Students receive ratings for every part of the day on their performance regarding areas they need to improve upon. This data is put into software to see how students are faring over time. Staff and families can monitor how the child is progressing. Once students meet a certain threshold for success, such as an 80% success rate, they are exited out of the program.

Relationship Building

Dr. Bruce Perry said it well: “Relationships are the agents of change.” All of the feedback and structure we might provide will not be successful in the long term for our students with the most needs without a caring person who they can trust in their life. Relationships are the foundation in which all other successes are built, both academically and socially/emotionally.

Going back to Check In-Check Out, we have found that it is this scheduled time with an adult who shows interest in and listens to the student to be the largest factor in improved behaviors and school performance. When a student is doing well, the adult celebrates the efforts that led to their success. When a student is having an off day, the adult is taught to inquire about why he or she is struggling. They also help the student connect where they have been successful during the day to the situations with less success. The hope is the student will start to generalize these positive habits of mind to all areas.

Relationship building has become a part of our acknowledgment system when noticing positive behaviors during the school day. In our school, students receive paw prints (our mascot is the bulldog) at unexpected times when they display expected behavior in sometimes problematic areas of the school. Instead of trinkets or prizes, students can bank these paw prints to have lunch and play a board game with the counselor or principal, help the custodian scuff out black marks, or work with the library aide to check-in and reshelve books. As they work and play with the adults, a relationship is developed beyond the formal student-teacher connection that often occurs in schools.

Personalized Behavior Plans

For those few students who do not respond to interventions and supports limited in duration and intensity, a school services team needs to come together and decide how to address an ongoing, chronic situation where a student is losing valuable instructional time and even preventing the teacher from being successful in his or her classroom. Although each child is different, most of these issues are either a) an outcome of a child’s home environment, or b) a mental health issue that is not being adequately treated.

We usually administer a functional behavioral analysis when beginning the development of a plan. This assessment helps determine why a student is acting the way they are, when and where this is usually happening, and what happens before and after the behaviors occur. It gives a school team more specific information about how to design an approach for this student to help him or her experience more success at school.

These plans detail the goals for the students, describe how often the team will reassess growth, and offer specific strategies that both the family and educators can utilize to help this student now and in the future. Strategies we have found successful in the past include frequent breaks, scheduled opportunities for movement, fidgets, and other sensory tools, regular counseling, outpatient therapy facilitated within the schoolhouse, and individualized instruction regarding acceptable choices.

Students are involved in every step of this plan development to help ensure buy-in and a sense of ownership.

If all else fails…

If a student has not experienced long-term success after a considerable amount of time, effort and supports have been provided and implemented, we know within reason that a student is going to need more accommodations than what is currently available within the regular education programming. At this point, we might look at a special education referral for an emotional or behavioral disability, hopefully with parents in agreement.

Having a system in place that creates consistency with instruction and is flexible enough to accommodate a student’s needs allows for a school to properly address almost any situation in the building. In the end, a student will receive what they need. It’s a matter of determining what that need is and monitoring the progress of the implementation of the intervention and other supports. The ultimate goal is to help every child be able to experience and build upon success as well as see themselves as a learner.

Matt Renwick is an elementary school principal in Mineral Point, Wisconsin and author of multiple books, including 5 Myths About Classroom Technology: How do we integrate digital tools to truly enhance learning? (ASCD, 2015). Learn more about Matt on his website, mattrenwick.com, and by following him on Twitter @ReadByExample; this article was originally posted to Matt’s website.