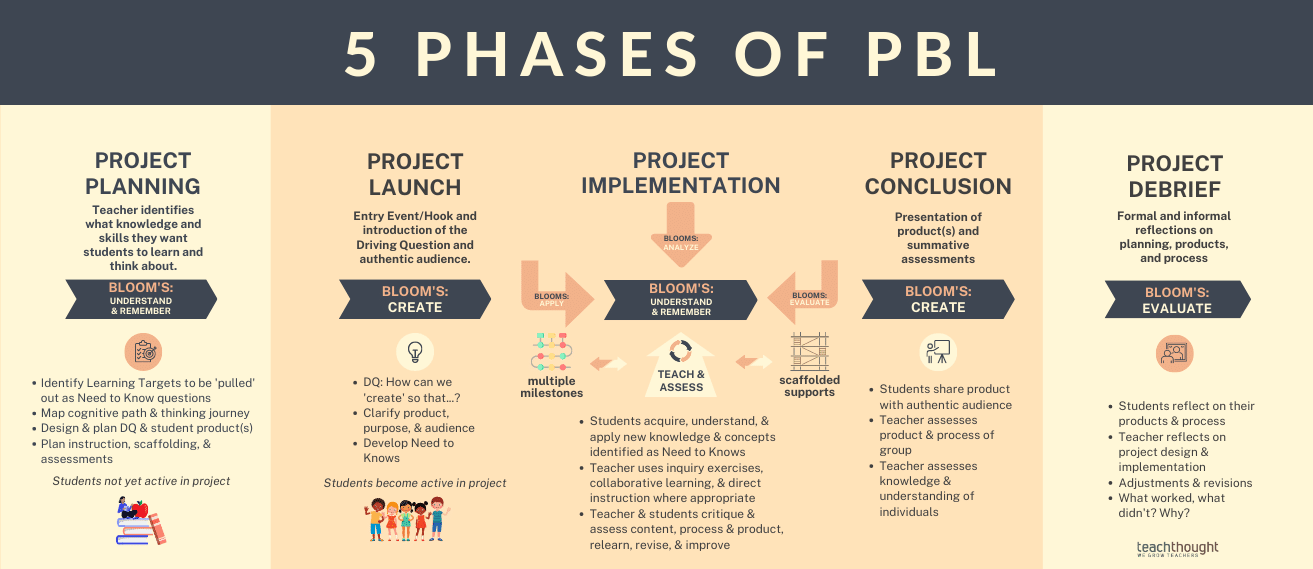

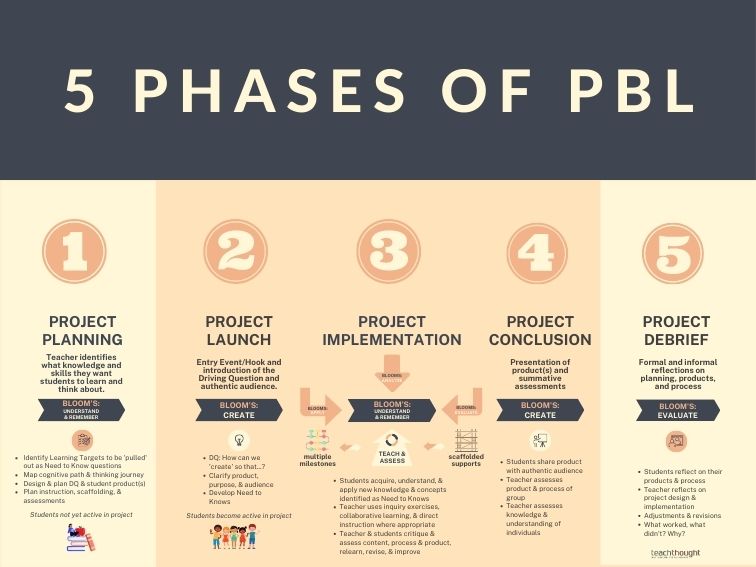

The 5 Phases Of Project Based Learning

contributed by Drew Perkins

Project-based learning experiences can range from highly complex in scope, scale, and timeline to much simpler versions with more limited complexity and sophistication.

The through-line in all of those instances is a set of steps or phases that include specific features and practices meant to help leverage specific outcomes. With that in mind, here’s an overview of the PBL process through the lens of five phases to help educators better understand the big picture so you can more effectively plan and implement the details within those phases.

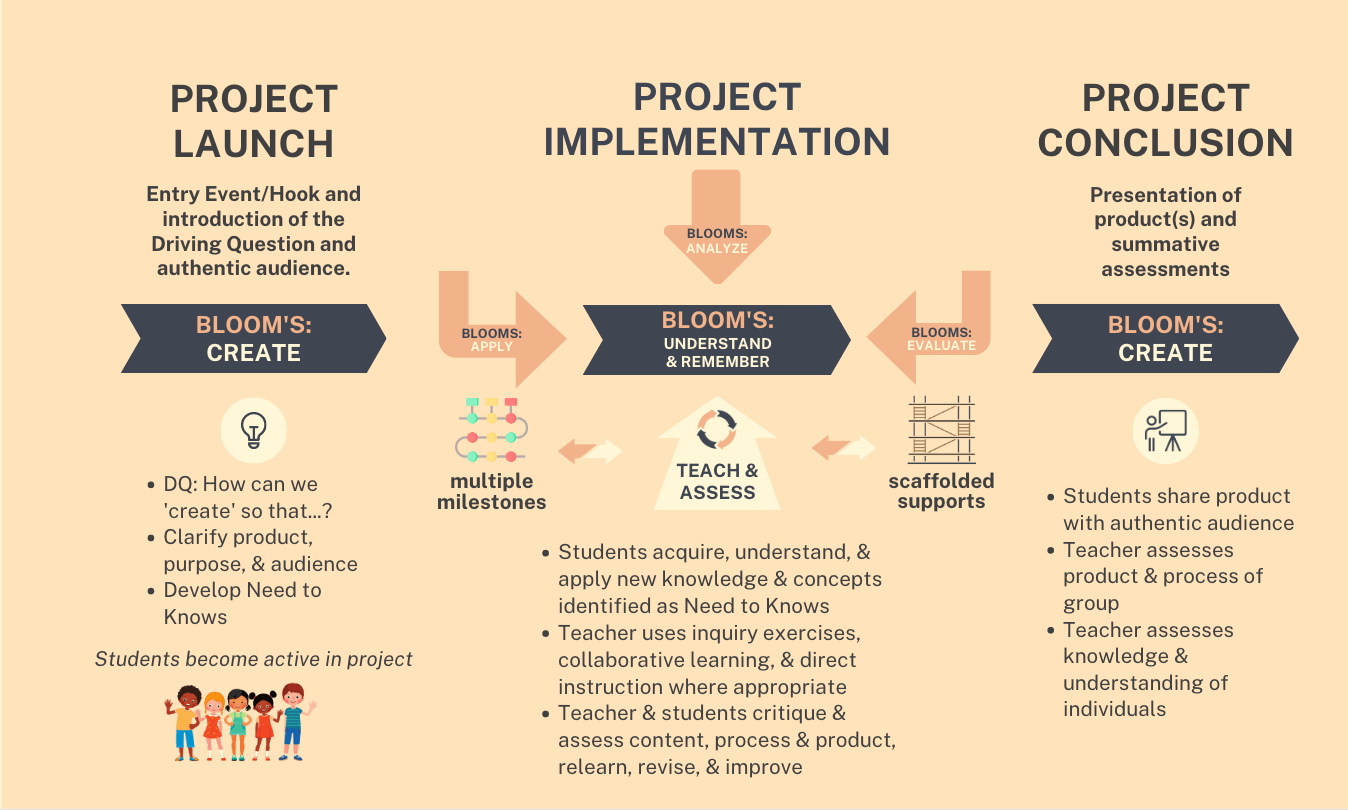

One of how we often talk about project-based learning in our Foundation of PBL workshops is by using Bloom’s Taxonomy as a sort of overlay. While there are some valid criticisms of this framework, and perhaps others that some may prefer, I think it is useful for its simplicity and the widespread teacher familiarity with it. In our workshops, when we discuss the idea of Using Project-Based Learning To Flip Bloom’s Taxonomy For Deeper Learning it often creates ‘a-ha’ moments. Thus I thought it would be useful to include in the accompanying graphic and a brief explanation of the connections in the last paragraph of each phase below.

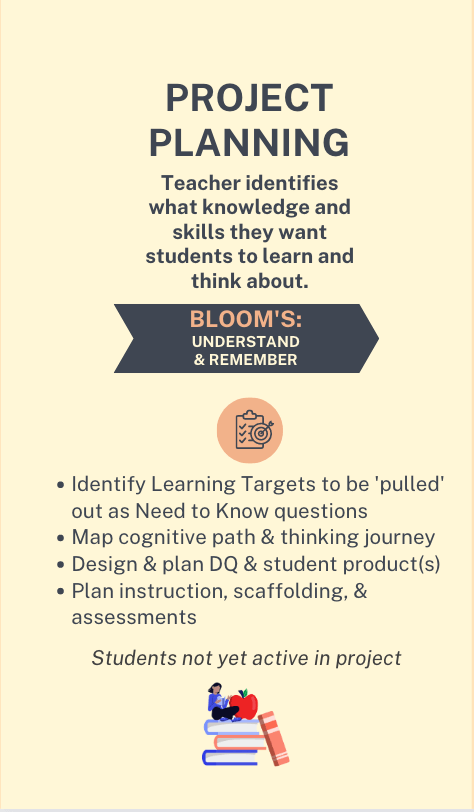

Phase 1: Project Planning

Before you begin your project with your students you’ll need to do the proper planning. This generally happens without student input although I have seen rare occasions where students can co-create PBL experiences with the guidance of an experienced educator. Most teachers have a set of content standards and learning targets they are responsible for and a risk of working with students to co-plan projects is the plan and project doesn’t end up including those outcomes, perhaps because the project aimed largely at what student’s found interesting.

Before you begin your project with your students you’ll need to do the proper planning. This generally happens without student input although I have seen rare occasions where students can co-create PBL experiences with the guidance of an experienced educator. Most teachers have a set of content standards and learning targets they are responsible for and a risk of working with students to co-plan projects is the plan and project doesn’t end up including those outcomes, perhaps because the project aimed largely at what student’s found interesting.

I’m not suggesting teachers shouldn’t consider student interest, quite the contrary, but the project planning phase is where teachers map the cognitive path and thinking journey they want their students to traverse. With that path clarified, and a Driving Question and student product(s) that align with those thinking and learning goals, it is time to plan out the timeline, including the scaffolding and assessments.

In this phase, students are not yet active in the project and teachers are identifying the things they want them to understand and remember (Bloom’s). This is the knowledge and concepts you’ll ask them to think critically about and with through the project, and you’ll want to consider which are just basic knowledge to be remembered and what lends itself to meaningful application toward deeper learning and understanding.

Phase 2: Project Launch

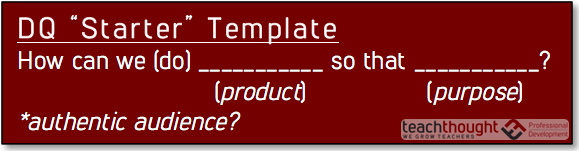

With your planning completed it is now time to invite the students into the project as active participants! The launching of a project can take a few forms and includes some sort of Entry Event or Hook to help create context for students and generate interest. From there you’ll want to introduce your Driving Question and authentic audience, both important tools to help unlock critical thinking.

With the students joining the project in this phase you’ll use your Driving Question to unpack (and model) the list of questions they’ll need to know to answer that DQ. This Need to Know list, and the process it demands, is a vital part of Why Creating A Culture Of Inquiry Is So Important. We advocate for clarity on product, purpose, and audience and a DQ that includes create (Bloom’s), or some synonym like design, develop, author, etc.

Phase 3: Project Implementation

In this phase of the PBL process you’ll be teaching, scaffolding, and formatively assessing as you ask students to learn, think more deeply about, and make connections with the content, skills, and knowledge that you identified (and likely more) in the project planning phase. Depending the scope and scale of your project you’ll have multiple milestones, both in terms of the process and product, but also in significant pieces of content to be learned.

In the project implementation phase you’ll engage students’ cognition with the planned teacher moves from phase 1 that include inquiry exercises, collaborative learning activities, and direct/explicit instruction where appropriate. While sometimes unfairly conflated, PBL is not the same thing as ‘Discovery Learning’. The role of an effective teacher is to determine when to use appropriate teaching strategies. While some may ask the question, PBL Or Direct/Explicit Instruction, What Works?, this is a false binary and students should not be left to figure out or ‘discover’ new knowledge on their own.

As the accompanying graphic shows, multiple pieces of Bloom’s Taxonomy are involved in this phase. It is in the project implementation that we ask students to do the apply, analyze, and evaluate critical thinking with the content and knowledge (what we want them to understand and remember).

Phase 4: Project Conclusion

As your project work wraps up students, and their groups, will be preparing to present their product(s) to the authentic audience. You’ll also want to summatively assess each individual to be sure they learned the content knowledge you intended. In our workshops we suggest some useful splits and balances in terms of grading and accountability but in general I suggest a much heavier weight on individual accountability than group.

As students share their findings and likely present to their authentic audience in service of what you’ve asked them to create (Bloom’s) we advocate for using a single-point rubric to help foster increased critical thinking. Once presentations and assessments of them are complete it is a great time to help students learn how to hold themselves and their peers accountable. These, sometimes hard, conversations can be valuable tools in developing collaboration skills but it is important to structure them for developmental appropriateness.

Phase 5: Project Debrief

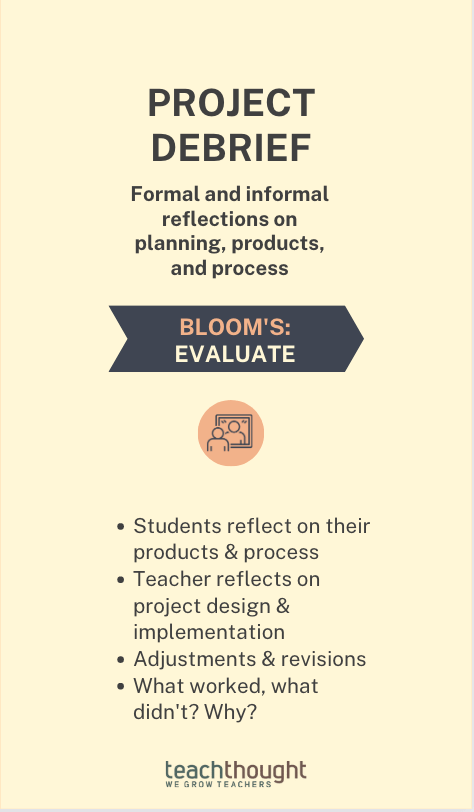

Once the dust has settled and the meat of the project is done it can be easy to move on but don’t forget reflection! Obviously, you’ll want to consider what went well in your project and what didn’t. What would you do differently if/when you used this project again? What adjustments and revisions might you make for future projects?

Once the dust has settled and the meat of the project is done it can be easy to move on but don’t forget reflection! Obviously, you’ll want to consider what went well in your project and what didn’t. What would you do differently if/when you used this project again? What adjustments and revisions might you make for future projects?

In addition to your professional reflections, there is much learning to be had by asking students to evaluate (Bloom’s) their performance and learning in the project. What worked for them and what didn’t, and why? This metacognitive process is a great way to consolidate learning and think about themselves more deeply as learners.

From Big Picture To Finer Details

The process of planning and implementing PBL is certainly more complex than this piece and the accompanying graphic illustrate. In our Foundations of PBL Workshops and supportive coaching conversations with teachers we’re better able to unpack those kinds of details and our free PBL Workshop Tools and Resources page that includes our planning documents and more can be useful as well. That said, without a clear overview and understanding of the entire process teachers can struggle to get PBL right and I hope this explanation and illustration are helpful in that regard.