“A voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles.”

That’s one very dry, but interesting way to describe play. The role of play in learning–given the chance–is incredible–both in intensity, duration, and impact everything else connected to the brain. The video below takes a look at play through the lens of games (along with a perhaps distracted two minute look at the origins of the word soccer).

It also offers some clarity on the difference between a toy, a puzzle, a conflict, a competition, and a game.

Interactive play with no goal is a toy.

Add a goal and a challenge and the toy is a kind of puzzle.

Add other agents, or involved participants, and suddenly the toy turned challenge turned puzzle is a conflict.

If you can’t interfere with other participants (like a marathon), you’re in a competition.

If you can interfere (as in basketball), it’s a game.

3 Criteria For A Game

To qualify as a game, it must (According to computer game designer Chris Crawford’s criteria), have 3 characteristics. They are:

1. Interactive

2. Goal-oriented

3. Involves other agents/participants who can interfere with and influence one another

So then, school and life itself. But then why aren’t school and life “fun”?

It has to do with delayed rewards (if any), changing rules, murky terms of success, and a lack of clear feedback. The video ends clarifying perhaps the most important function of games: to allow us to more quickly and efficiently “feel the (psychological) rewards we need without all of the unknowns of life.”

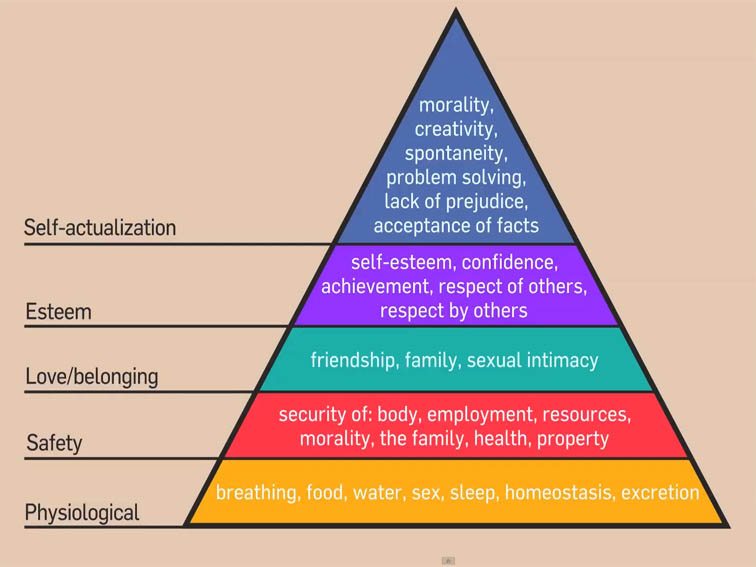

So what does any of this have to do with Maslow’s Hierarchy? We only tend to “play”–to freely interact, show curiosity, experiment, and self-manage–when other more critical psychological needs are met. And notice where self-actualization and esteem are in relation to physiological and safety needs.

Put simply, until fundamental human needs are met, play–and likely any kind of enduring, relevant academic performance–isn’t going to happen.