What It Was Like To Meet Wendell Berry

by Terry Heick

“Because of the penmanship.”

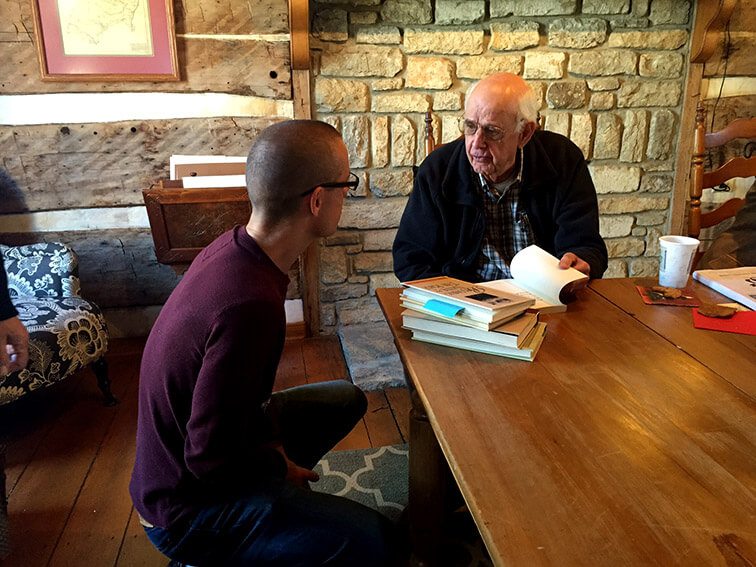

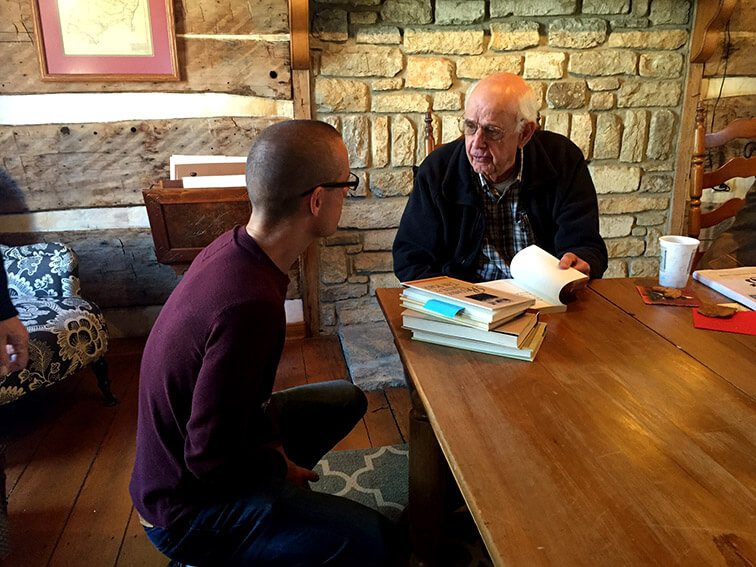

The man I’d been chasing for ten years now had been speaking with two authors seated next to him at what appeared to be a wooden supper table, but covered in books and coffee. After a decade of endless and painful reconciliation between belief and behavior, for me, a new sort of marker was here.

I was at a book signing, and between books to sign, there sat Wendell Berry, 18 inches from me, trying to explain that he read recently of a group of students studying the Declaration of Independence, but the students couldn’t read it. The other authors he was speaking to seemed to think that was because of their inability to understand. It seemed (to me) to be Wendell’s point that the penmanship was the issue, so I offered that up to jut my way into things. I had waited too long for this moment.

Wendell turned towards me, first with his eyes, then head, then the rest of his body. “That’s right.”

“They don’t teach cursive in school anymore,” I offered. I didn’t bother to tell him I thought that was probably a good thing. I was spineless.

There was no line behind me, which turned out to be quite the boon. The signing was 3 hours long, and here 20 minutes before it ended, there were only 8-10 people left milling around and talking quietly.

How I got to this cabin in Henry County, Kentucky on a sunny December morning, involves, maybe more than any other principle, the matter of place. I was teaching English in Spencer County, Kentucky, when the social studies teacher I often talked pedagogy with asked me if I had read Wendell Berry. Being an English teacher from Kentucky, I knew saying no would destroy my credibility, but I’ve never had much of that anyway, so I was honest. I knew the name, I explained, but hadn’t read anything.

Berry is known nationally as an author, but in rural Kentucky he means something different. His work as a farmer was the same as the work of any farmer. He was a Kentucky farmer before he was Wendell Berry. He was his father’s son, and his grandfather’s legacy. This place made him the way sunlight makes a forest. Being an author and advocate and teacher and farmer made him—in this place—something different than he would be in say, New York or San Francisco. William Faulkner is different in Biloxi than he is in Toronto.

So one day soon after, said social studies teacher brought me a book by Berry. I can’t recall which one. Maybe The Agrarian Essays? Reading the first two or three pages, I knew I was doing more than reading. It was like being shaven at first. I’d read and feel the words scrape across my mind, only it was a bit more jagged. Disruptive. Agitating soil may be a better metaphor. I read and felt haunted.

This was unsettling at first. And Kafka said reading should be unsettling.

“I think we ought to read only the kind of books that wound or stab us. If the book we’re reading doesn’t wake us up with a blow to the head, what are we reading for? So that it will make us happy, as you write? Good Lord, we would be happy precisely if we had no books, and the kind of books that make us happy are the kind we could write ourselves if we had to. But we need books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone, like a suicide. A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us. That is my belief.”

The word suicide resonates. Part of me was dying. For the first time in my life, I had read something that deeply affected me. And my first reaction was to chase it. So I did.

I read voraciously. I ladled out ideas onto pages and pages of white paper and concept maps. I talked to others to see if they’d read Berry. I copied his writing—not plagiarized it, but tried to reproduce it the same way a doctor’s child may grab a stethoscope to be like his mother or father. I did so to better understand what I was reading, so I could better understand who I was.

I pulled my children from public school and started homeschooling them, hand-picking everything they read and did. I started TeachThought. I renewed my vows with my wife. I shopped local and tried to explain ideas like scale and interdependence to my children. And for the first time in my life, I was aware of exactly who I was, partly as a function of where I was. The Kentucky streets I had grown up in weren’t streets at all, but places.

I won’t explain how or why (you’d have to read to understand, and the point of this isn’t to get you to read Berry.) But in turn I developed fierce anxiety. It was all too much, too fast. It was awful. 10 MG of Celexa every evening awful. What had I done? Why had reading broken me? It probably has something (a lot?) to do with my personality. I am pre-wired to swoon or cry or mistake emotions for thoughts. I’m a wreck of a person.

But as I began to reorganize my behavior in alignment with a new sense of self, I also felt the urge to actually see the man that had wheeled me to this precipice. Reading him agitated and tore at me. It was like the shatter of thin glass. It shrieked and writhed and squealed. It stained and bruised and punctured. I had to thank him for nearly killing me. After 10 years of reading, and dozens of counseling sessions and personal epiphanies, here I was standing beside the author of my own anxiety.

“I saw you at Actor’s Theater last year with Gary Snyder,” I stammered. “Gary said the first thing we should teach all children is proper penmanship. I asked you about education? What we should teacher students in school?”

His eyes lifted as he finished signing the first book. More than anything else, his presence came off as comforting.

“I’m not sure what good it is to teach children the things we do,” he explained.

One of the most significant opportunities for growth in education, in my small mind anyway, lies in curriculum. Content. Standards. The what of learning seems more important than other more popular topics, like how and where. So of course I agreed.

“What good is any kind of knowledge without self-knowledge to shape it?” I responded.

“Absolutely right. You’ve got that right. Yes,” He agreed with enough enthusiasm to make me wonder if someone else had their hand in the back of my head and used my body like a Ventriloquist. Better introduce myself.

“Mr. Berry, my name is Terry Heick, and I’m a teacher. Your work has influenced me greatly. One of the things I do is take your ideas, and help contextualize them for other teachers. Or try anyway.”

“Well, I’m not sure I’ve had any ideas. These ideas aren’t mine. I got them from other people, who got them from other people. And so on.”

“In that way, you’ve also brought me to other authors—Wes Jackson, for one” I say, nodding towards the “Becoming Native to this Place” on the desk between us. Jackson spoke of place like a character, setting, history, and matter of eternal human conflict.

You can’t be aware of what you’re doing without being aware of what you’re undoing.

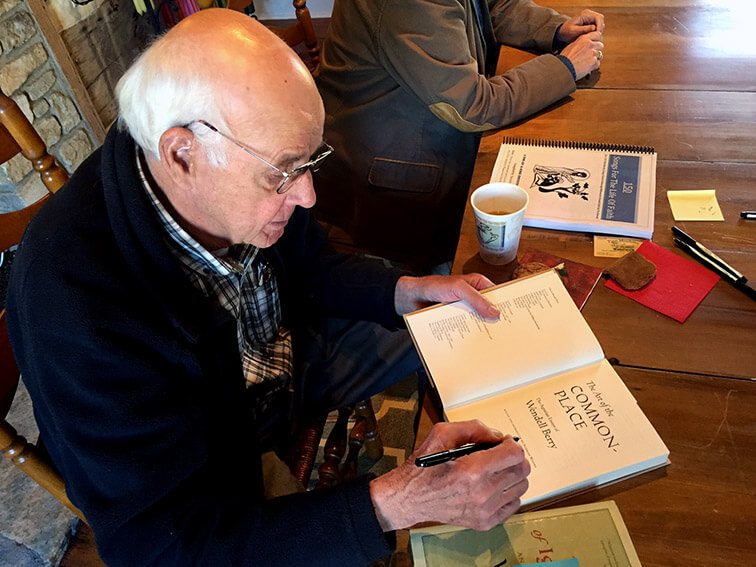

Wendell didn’t respond, continuing to sign the four books I had placed in front of him, his pen motioning soundlessly across the page.

“I’m sorry,” I said.

“For what?”

“For asking you to sign so many books.”

“Well, it is much easier to sign them than it was to write them.”

I was aware at one point that my talking might be keeping him from signing, so I stopped and just rocked back and forth on the sides of my feet, not knowing what I should be feeling.

The man I had chased for years sat in front of me. I’m not sure what I expected. He was simple in conversation. Had a pleasant smile. Drank plain black coffee. His eyes were calm and satisfied. He wore a plaid shirt and wire-rimmed glasses, and had a pleasing southern drawl. When he was done signing, I felt the urge to hug him. And even though he was sitting down, I did. He patted my arm and thanked me, and I floated out of the room in a small bookstore that was suddenly empty and quiet.

And that was that. After waiting for ten years, as a moment in the present anyway, it was all over. Meeting Wendell Berry was somewhat about meeting a person that had changed my life. I was star struck for sure. It was also about me confronting myself and my tendency to manufacture my own suffering effortlessly. Meeting Wendell Berry also finished something for me. This wasn’t a matter of destination—me arriving here to meet him. It was a matter of place.

I had taken his ideas formed here and integrated them there–into my place. My home and my community and my family and my work. Necessarily so. Where else can I be but in the place that I am? In that way, he had affected countless places in and around St Matthews and Clifton and Middletown, Kentucky by lighting them up in my mind.

And today, I had driven out to Henry County, to his place. This was the bookstore of his foundation. Of his life’s work. Close by was his farm—also his place. This was land he had worked for decades, and his father and grandfather before him. His affection and effort and skill had turned that field into a place. It was uniquely known to him. It was the setting for struggle and knowledge and other narratives that would die with him when he passed.

Places change as people remember and misremember, ignore and forget. Sometimes, they completely disappear. If you’ve seen Gangs of New York, the ending gets at this idea some. (You can see it here.) All of the factions and characters and human upheaval, all quieted by time. The ending shot shows the graves of the characters as the modern New York City erupts around it, so many stories—and so many places—dying with them.

Near the brick road in Clifton, Kentucky where I had grown up—State Street—was where I had my first kiss. That was a place, and I knew it well. I can see it as it stood 26 years ago clearly in my mind. That place doesn’t exist for many other people, I’m sure. And as a place, it exists only inside of me. When I die, as a place that spot on that wall will quietly disappear. No one will notice. The tree I used to climb, as a place of security and solitude to me as a boy, will also, as a place, disappear.

In meeting Wendell Berry, my crude vision of him as a sage, mad farmer had died. Wendell Berry the man juxtaposed cleanly with Wendell Berry the writer. They were markedly different. The former is sedate and affable; the latter full of vision and angst. But they were all a matter of meaning—meaning constructed in my mind through schema gathered in my place. They were the same.

When I read Berry, I create meaning with my own native schema. (Native schema is a bit redundant, because where else can it come from?) He is the hand, and my own people and places are the sock puppets. As a reader, I have to transfer his ideas into mental language I can relate to. Symbols recognizable to me; spaces that are places to me.

Just as experience turns spaces into places, meeting Berry had turned him from an author I was influenced by, to a man I could sit and have coffee with. A man who had trouble hearing, and smiled easily, and waited for people to get his jokes without rescuing them with an explanation. And this wasn’t a he puts his pants on one leg at a time like everyone else moment, but something more contextual and full. The many scars and layers and angles and stories and missing buttons of a man merged to become something whole.

Wendell Berry had leaped from my mind–where I chased him endlessly without ever gaining an inch—to a plain chair with a wicker back and a stain a shade darker than the table in front of him, his pen marking book after book as the people talked quietly around him, smiling and nodding and reconciling meaning of their own.