by TeachThought Staff

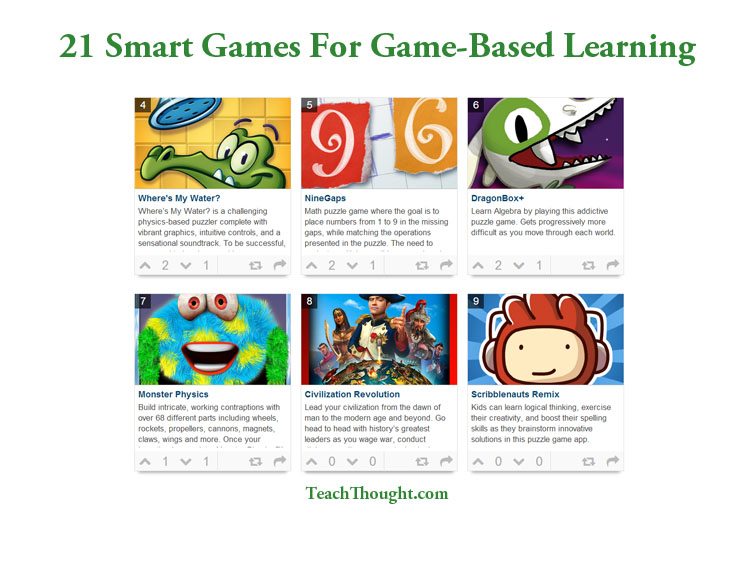

There is a difference between gamification and game-based learning, and this post focuses on the latter.

Essentially, game-based learning means to learn through games.

Learn what and how–and through what games–is the less straight-forward part.

There is seemingly a disconnect between what students learn while playing games (e.g., problem-solving, visual-spatial thinking, collaboration, resource management) and the pure academic standards most teachers are interested in promoting mastery of.

But there is also the simple truth that few things are as engaging–for adults and students alike–as a well-designed video game, which might just make the following list of smart video games for learning useful.

If you’re looking for somewhere to start, might we suggest Civilization VI (this is the link for the Nintendo Switch version but it’s available for iOS and other platforms) or Portal 2 (this is PS3 version, but it is also available for other platforms)?

This post contains affiliate links. This means we receive an absurdly small % of any sales made from clicking a link. If you want to make sure Amazon or other retailers receive all of the profit, just search the respective retailer’s store to find the item. You can read more about this policy here.

14 Games For Game-Based Learning By Grade Level

1. Minecraft: Education Edition

Subjects: Math, science, literacy, art

Why: A flexible sandbox platform with curriculum-aligned worlds that promote creativity, teamwork, and cross-curricular learning.

https://education.minecraft.net

2. Osmo (Various Games)

Subjects: Math, spelling, coding

Why: Combines physical interaction with digital play for early learners. Excellent for foundational skills and hands-on exploration.

https://www.playosmo.com

3. Prodigy Math Game

Subjects: Math

Why: Gamifies math practice with a role-playing adventure format, adaptive questions, and curriculum alignment.

https://www.prodigygame.com

4. Zoombinis

Subjects: Logic, pattern recognition

Why: A classic puzzle game that strengthens deductive reasoning and early computational thinking through charming and challenging gameplay.

https://www.zoombinis.com

5. Toca Life World

Subjects: Storytelling, social-emotional learning

Why: Open-ended creative play helps children develop narrative and interpersonal skills in a risk-free digital environment.

https://tocalifeworld.tocaboca.com

6. SimCity EDU

Subjects: Civics, environmental science

Why: A city-building simulation that tasks students with managing pollution, energy use, and community well-being, encouraging systems thinking.

https://www.glasslabgames.org/game/simcityeduhc

7. The Oregon Trail (Modern Version)

Subjects: History, literacy, decision-making

Why: Teaches historical context, risk management, and narrative through a simulation of 19th-century frontier life.

https://apps.apple.com/us/app/the-oregon-trail/id1538909280

8. Kerbal Space Program

Subjects: Physics, engineering, astronomy

Why: A complex space flight simulator that lets students experiment with design, thrust, gravity, and orbital dynamics.

https://www.kerbalspaceprogram.com

9. Scratch (by MIT)

Subjects: Computer science, storytelling

Why: A free platform where students learn the basics of coding through interactive stories, games, and animations.

https://scratch.mit.edu

10. DragonBox Algebra 12+

Subjects: Algebra

Why: Uses visual metaphors and game mechanics to intuitively teach abstract algebraic concepts.

https://dragonbox.com/products/dragonbox-algebra-12

11. Civilization VII

Subjects: History, geography, economics, government

Why: A turn-based strategy game where students lead a civilization across eras, promoting critical thinking and understanding of historical cause and effect.

https://store.steampowered.com/app/289070/Sid_Meiers_Civilization_VII/

12. Portal 2

Subjects: Physics, logic, engineering

Why: A visually engaging, story-driven puzzle game that strengthens spatial reasoning and problem-solving. Includes level creation tools for added challenge.

https://store.steampowered.com/app/620/Portal_2/

13. Assassin’s Creed: Discovery Tour

Subjects: History, art, architecture

Why: Offers non-violent, interactive explorations of Ancient Egypt, Greece, and the Viking Age using museum-like tours built into AAA game environments.

https://www.ubisoft.com/en-us/game/assassins-creed/discovery-tour

14. Democracy 4

Subjects: Civics, politics, economics

Why: A simulation where players manage policy decisions, budgets, and voter satisfaction, providing insight into real-world governance.

https://www.positech.co.uk/democracy4

15. Human Resource Machine

Subjects: Programming logic

Why: A quirky, code-based puzzle game that introduces the fundamentals of computer programming through logic and visual sequences.

https://tomorrowcorporation.com/humanresourcemachine

Play FreeCell Solitaire Card Game Online

14 Games For Game-Based Learning By Grade Level