What Is The Role Of The Teacher In The Classroom Of The Near Future?

by Terry Heick

Schools, along with libraries and museums, are curators of culture.

That is, they survey various (metaphorical) landscapes and separate the stuff the stuff worth saving from the rest. This means that teachers are among the earliest curators of knowledge, taking a content area, deciding what’s worthy of further study, and distributing it for examination.

This is not a minor responsibility, being asked to weave a simultaneous affection and lasting intellectual lust for what is by definition academic ‘stuff’—factors of immigration, the Pythagorean Theorem, Homer’s Odyssey, etc.

See also The Big Picture: 8 Ways To Future-Proof Your Teaching

What Is Teaching?

Historically, teaching could be reduced to two simple questions: What’s worth understanding and how can I package that so that students may understand?

Increasingly, technology is being used to accomplish this. See the (Elements of a Digital Classroom). Whether it’s a learning management system used to gather and organize learning materials, a digital index of academic standards, a tool to visualize data, or an adaptive learning platform used to practice and assess concepts and skills, if public education wants to operate and perform at the scale it seems intent on operating and performing at, technology is going to have to play a critical role.

That said, if public education wants all students to master all content and succeed in every way every day no matter what the cost, teachers alone aren’t enough. Of course, from a philosophical standpoint, there’s a lot to consider. By deciding what stays and what goes—what’s worth understanding and what’s not—teachers have quite a bit of power, and like all power, it can be applied in various ways.

1. The ‘teaching’ can be a kind of social assimilation and cogntive conditioning where the teacher passes on both knowledge and bias.

2. It can be knowledge distribution—clinical and matter-of-fact, modeling skills and issuing facts.

3. Or, it can be based in an artful critique, where they ‘point where to look but don’t tell them what to see.’

Historically, as teachers have taken the world and shaped a curriculum out of it, they have done more numbers 1 and 2 than 3.

They’re knowledge curators, so they curated. Of course, in the modern era of outcomes and standards–based education systems where all content is indexed, catalogued, parsed, sequenced, aligned, assessed, and remediated, the learning process has taken on an industrial tone with work that mimics that of machines. The content is no longer up for debate, written in standards that, while more open-ended than they seem, aren’t up to the teacher to describe.

The original question of pedagogy– What’s worth understanding, and how can I package it so that they (whoever they are) may understand?—can now be reduced to How can I package these standards so that they may understand? That is a major difference, reducing the ‘curation’ to mere distribution.

But there’s a problem with this. As teaching and learning becomes more universal, it becomes less authentic. As it becomes more global, it becomes less local. As it becomes more everyone, it becomes more no one at all.

Place Matters

Place matters, because that’s where students come from, and where the result of learning is ‘applied.’

A teacher in New York needs to understand what makes New York different than Mumbai. The habits of the people and the shape of the place shape the content—what’s most important to know and how it is most ideally approached and understood isn’t the same everywhere.

As curriculum becomes an indexed lists of standards to be covered, and as literature becomes a suggested reading list that isn’t a ‘suggestion’ at all, the potential for the teacher to artfully relate students and content is reduced. Without an elegant and agitating and fantastic connection between learner and content, the whole thing becomes about measurement and procedure—an industrial and dehumanizing process that amounts to an intellectual force-feeding.

The net effect here is important. Every ‘place’–every community, neighborhood, and family has its own history; every student has their own affections and needs. Every student is wonderfully asymmetrical. This requires care.

Teachers, as humans, are a kind of mix between Google, pinterest, and YouTube—searching the world, saving what fits, and distributing it in compelling ways. Great teachers are master curators, uniquely able to see the content, each learner, and their ‘place’ in a way that literally no one else on earth can.

Even an adaptive computer algorithm.

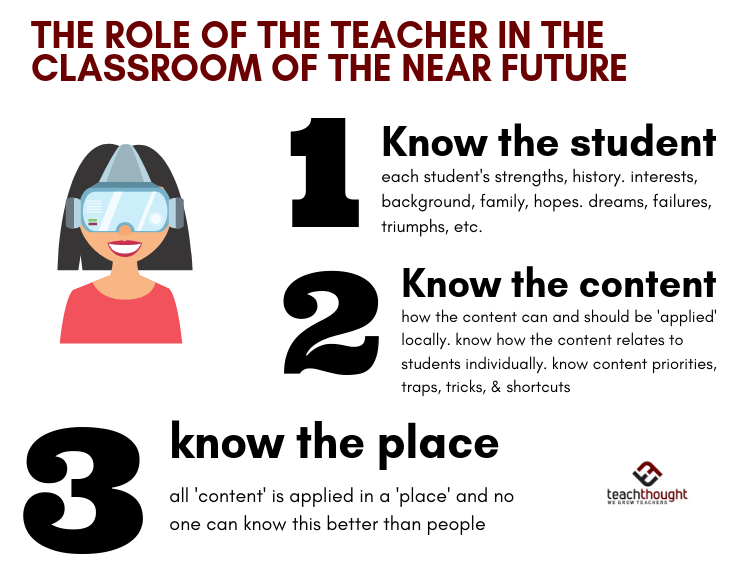

3 Roles For The Role Of The Teacher In The Near-Future Classroom

1. Know the student

The teacher will always be best at the ‘big picture’ of each student’s strengths, history. interests, background, family, hopes. dreams, failures, triumphs, etc. Working together with technology like artificial intelligence, teachers can reconcile data with the ‘human’ view of the student in front of them.

2. Know the content

The teacher will always be the best resource to understand how the content can and should be ‘applied’ locally. The teacher will ideally know how the content relates to students individually and know the ‘content’ well enough to see all priorities, traps, tricks, and shortcuts that make sense for that student in that place.

3. Know the place

All ‘content’ is applied in a ‘place’ and no one can know this better than people–and until an AI-driven robot can do this better than a human being, this will be best done by a teacher who themselves have a history and connection with that place.

The Role Of The Teacher In The Classroom Of The Near Future