Updating The Gears Of Education

by Terry Heick

I. Education is both industrial and fundamental; the product of engineering and affection.

II. This makes it a human process, full of incredible complexity that mirrors that complexity inside each of us. This, in turn, requires a response that is equally complex and decidedly clever.

III. In the first century of an increasingly global movement to provide public education, we have turned to our own rationality, and established systems.

IV. These systems parallel similar transitions from small farms to commercial agriculture, small shops into mega-stores, and interpersonal storytelling to seeking our ‘stories’ from Hollywood and social media, all increasingly driven by technology.

V. Evaluated with a rational mind, this is neither good nor bad but only change–or even ‘progress.’

VI. Education’s progression has led us to our current system. This system is designed to publish common goals that drive our common actions and performance.

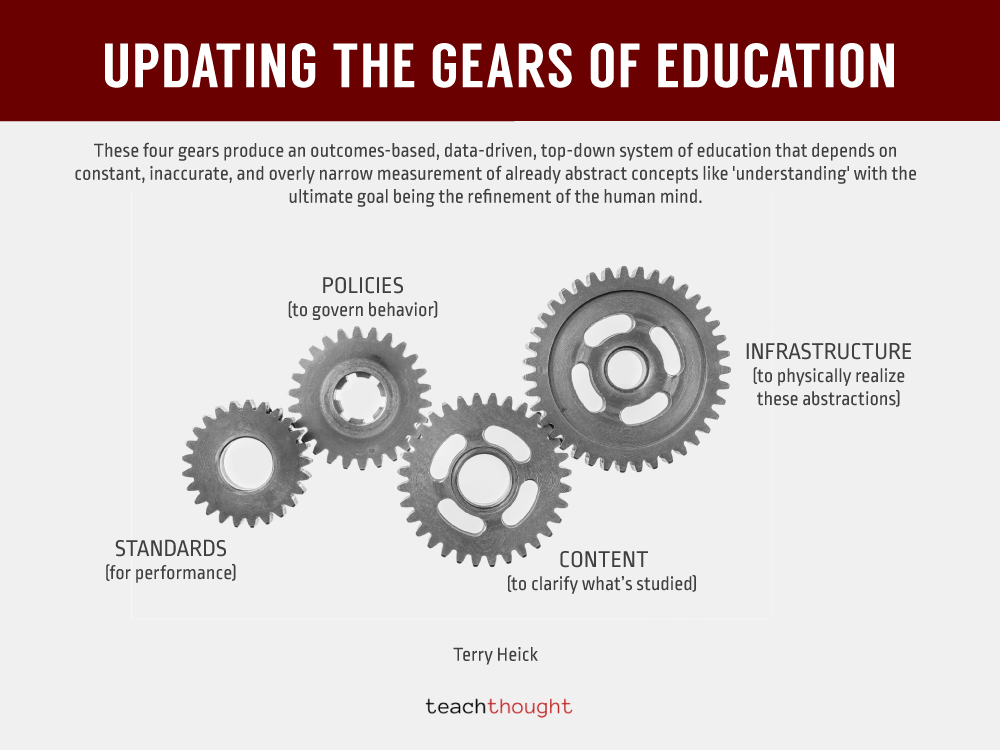

VII. Within this system, there are (at least) four subsystems. (These can be thought of as gears.)

- Standards (for performance)

- Policies (to govern professional behavior)

- Content (to clarify what’s to be studied)

- Infrastructure (to physically realize these abstractions)

VIII. Energizing the above gears are four catalysts:

- Strategies (to design and plan for learning experiences)

- Assessment (to measure the effectiveness of those experiences, and thus the planning and design)

- Data (to quantify progress and deficiency to inform necessary revisions)

- Collaboration (to both share and homogenize the entire effort)

IX. These four gears produce an outcomes-based, data-driven, top-down system of education that depends on constant, inaccurate, and overly narrow measurement of already abstract concepts like ‘understanding’ with the ultimate goal being the refinement of the human mind.

X. In the case of most schools, this translates to hundreds and even thousands of minds, each with their own stories, interests, insecurities, and needs. Thousands of spectacular complexities.

XI. The word ‘mind’ suggests something different than the current gears and catalysts provide. A ‘brain’ may seek an input to produce an output, but a mind is curious and wants to play.

XII. Performance on an assessment can be measured, but truly measuring understanding is less precise–and both fail to see the bigger picture: How can we help students see for themselves what’s worth understanding for themselves? Our curious solution so far has been to simply hand it to them endlessly until they leave for ‘jobs.’

XIII. An outcomes-based system of education seeks only to produce outcomes. Its self-correcting systems, which glean their corrections from those strategies, data, and collaboration above, test and probe—with perfect rationality—what works and what doesn’t so that we can do less of the latter and more of the former until the latter is all gone.

XIV. It is plain to see, however, that this is not what happens. The outcomes we seek to cause are first industrial—acquisition of catalogued knowledge parsed into content areas.

XV. Presumably—and this is where I could be wrong–the hope is that proficiency of this cataloged content will lead to citizenship, affection, good work, happiness, and after a lifetime of humanizing it all, wisdom.

XVI. These ideas—citizenship, affection, good work, happiness, and wisdom–are purely irrational—abstractions that counter-balance systems-thinking and scientific approaches.

XVII. This means that we have designed a system of education that both marginalizes and patronizes the abstractions it hopes to produce. And its inherent rational gears—especially assessment and data—are impotent to respond to that which is irrational.

XVIII. This is neither clever nor our best thinking.

XIX. This cleaving of the rational and the irrational—of art and science—mutes our collective complexity as human beings. This suggests that we might update our gears to once again marry the design of our system with the desired end result.

XX. To that end, we might consider updates these iconic gears and catalysts with new thinking whose cleverness and artistry mirrors our own as human beings–and we could do worse than to start with replacing our focus of standards and policies with students and communities.