What Should Students Learn? What Might They Learn In The Future?

by Terry Heick

This post is sponsored by Adobe Presenter 9. You can read more about our sponsored content policy here.

A lot is implied in the content areas we choose to disperse the world through.

That’s essentially what classes and content areas are–perspectives to make sense of the world. If the world changes, should they change?

These words and phrases that we now associate with schools, teachers, and assignments reflect our priority as a culture. This is the information and thinking we value and want our children to understand. It also implies what we think is useful, presumably (unless we’re intentionally teaching content that we think is use-less).

The Past

While that content changes some as students move from Kindergarten to 12th grade, in general, the kinds of things we ask our 2nd graders to study are similar to what we have our high school seniors study. In classic education (in certain parts of the world anyway), ‘content areas’ were essentially categories–the Trivium (or ‘three ways’): Grammar, Logic, and Rhetoric.

Grammar taught students the basics of language (the symbols we use to label the world).

Logic taught analysis and relationships between those symbols.

Rhetoric taught students the fine art of manipulation–argument, theories, and, well, manipulation

The ‘trivium’ was designed to precede the Quadrivium (you guessed it–‘the 4 ways’)–Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, & Astronomy. After tackling literacy and analysis as younger students, older students moved to systems of analysis. (This is a very broad overview, and not at all the point of this post–just bear with me.)

Somehow, most schools in modern times have settled on the Humanities and STEM, with a North American student’s courses usually including English, Math, Science, and Social Studies as a kind of core. These collections of content are curated by experts into standards that are then formed into curriculum, units, and lessons.

Teachers take up these lessons and, mixed with iconic ideas like the quadratic equation, the water cycle, and William Faulkner’s use of symbolism, become the face of what students learn.

Content Should Reflect Cultural Values & Trends

But content is also deeply philosophical.

If we consider science, for example, what is now a ‘class’ was at one time a world-shifting way of thinking about the world that helped spur the Age of Enlightenment, and in many ways derailed theology and character training as the drivers of education.

Just as advances in technology-enabled the growth of science, the extremely rapid growth of technology we’re experiencing today is impacting our perspectives, tools, and priorities now. But beyond some mild clamor for a focus on ‘STEM,’ there have been only minor changes in how we think of content–this is spite of extraordinary changes in how students connect, access data, and function on a daily basis.

What kind of changes might we expect in a perfect-but-still-classroom-and-content-based world? What might students learn in the future?

Of course, any response at all is pure speculation, but if we draw an arc from classical approaches to the Dewey approach to what might be next–factoring in technology change, social values, and criticisms of the current model–we may get a pretty decent answer. This assumes, of course, a few things (all of which may be untrue):

1. We’ll still teach content

2. That content will be a mix of skills and knowledge

3. These skills and knowledge will be thematically arranged into ‘content areas’

Note that these classes are arranged as a hierarchy, starting with content for younger children (around 6-8 years old), all the way to university age (18-24 years old). All classes would (speculatively) be taught to all students of all ages, with changes in priority available for personalized learning based on age, local values, etc.

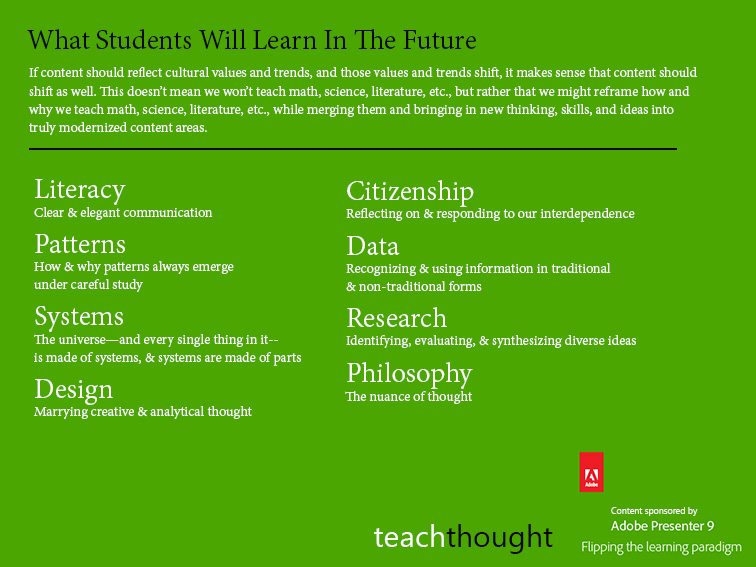

It’s also important to note that none of this means that in a system like this we wouldn’t teach math, science, literature, etc., but rather that we might reframe how and why we teach math, science, literature, etc., all while merging them and bringing in new thinking, skills, and ideas into truly modernized content areas.

What Students Will Learn: 8 Responsive Content Areas Of The Future

1. Literacy

The ability to read and write

Big Idea: Reading and writing in physical & digital spaces

Examples of traditional ideas and academic content areas included: Grammar, Word Parts, Greek & Latin Roots, The Writing Process, Fluency; all traditional content areas

2. Patterns

Repeated or recurring arrangements of elements, shapes, behaviors, or events that can be observed in nature, design, data, or systems, often revealing underlying order or structure.

Big Idea: How and why patterns emerge everywhere under careful study

Examples of traditional ideas and academic content areas include: Grammar, Literature, Math, Geometry, Music, Art, Social Studies, Astronomy

3. Systems

Organized sets of interrelated components or processes that work together to achieve a common goal or function within a larger framework.

Big Idea: The universe—and everything in it–is made of systems, and systems are made of parts.

Examples of traditional ideas and academic content areas include: Grammar, Law, Medicine, Science, Math, Music, Art, Social Studies, History, Anthropology, Engineering, Biology; all traditional content areas by definition (they’re systems, yes?)

4. Design

Design creates a plan or solution with purpose and intent, often blending functionality, aesthetics, and problem-solving.

Big Idea: Marrying creative and analytical thought

Examples of traditional ideas and academic content areas include: Literature, Creativity, Art, Music, Engineering, Geometry

5. Citizenship

The status and duties of a member within a community or nation, involving rights, responsibilities, and participation in civic and social activities.

Big Idea: Responding to interdependence

Examples of traditional ideas and academic content areas include: Literature, Social Studies, History; Civics, Government, Theology

6. Data

Information collected, measured, or observed that is used for analysis, interpretation, or decision-making, typically in a structured or raw form.

Big Idea: Recognizing & using information in traditional & non-traditional forms

Examples of traditional ideas and academic content areas include: Math, Geometry, Science, Engineering, Biology;

7. Research

The systematic and critical investigation into fundamental questions about existence, knowledge, values, and reason, often involving analysis, argumentation, and the exploration of different philosophical theories and perspectives.

Big Idea: Identifying, evaluating, and synthesizing diverse ideas

Examples of traditional ideas and academic content areas include: English, Math, Science; Humanities

8. Thinking/Philosophy

The process of reflective, logical, and critical reasoning to explore deep questions about reality, morality, knowledge, and human nature, seeking to understand and challenge assumptions, concepts, and beliefs.

Big Idea: The nuance of thought

Examples of traditional ideas and academic content areas include: Ethics, Literature/Poetry, Art, Music; Humanities

What Students Will Learn In The Future: 8 Responsive Content Areas For Tomorrow’s Students